The final piece of the sidechains puzzle: O(1) sidechain validation for miners.

History of Sidechain Development

Existing Work

In pursuing my goal of Bitcoin prediction markets, I was drawn to sidechains as the only realistic implementation strategy. I even sketched out some way that they would have to work, in early 2014. My friends an I worked on my own project, while waiting for sidechains to be developed.

After a while, we had completed so much Hivemind work that the bidirectional peg (ie “sidechains”) was slowing us down. I turned my attention to it, and was able to improve it in many significant ways. One of these was a requirement that the withdrawal proof use the ‘parent’ mainchain’s PoW, instead of the sidechain’s PoW. I pointed out that this effectively ‘privatized’ the sidechain, such that miners would have an incentive to ensure that the portfolio of active sidechains was optimal.

I presented on “Public Blockchain Ecology” in Summer 2016, commenting on why we would want to ensure that only “wise” sidechains (useful and non-combative) join the Bitcoin family. Then, in Milan, I took this point of view to its logical conclusion, and implied that we could solve the scaling contention with a sidechain (ie, not solve “scaling” itself, merely “the contention” over which tradeoff between node-resources and tx-fees is appropriate).

I did want to solve the scaling contention, but my trip to Milan held a second purpose: to push the sidechain-concept to it’s most unpopular conclusion! This would allow me to take a good look at all of the objections.

One Lingering Complaint

The sole remaining complaint about sidechains, was that they might affect “miner decentralization”. I’ve spent most of the time since then trying to figure out exactly what this complaint is about.

With some effort, I finally got to the bottom of this complaint. It was only possible, because the complain-ers both [1] suggested a Preferred Scenario “P”, and [2] admitted that “P” would be equivalent to Neutral Scenario “N” which could theoretically already be occuring.

Let me explain.

- The Preferred Scenario “P” was the ‘federated bidirectional peg’ which is secured by multisig. It is effectively equivalent to a bank or website: money goes into an address, data flows in a dark/isolated silo, the silo-software computes withdrawal requests, the multisig functionaries decide who/where to send the money, and they sign normal Bitcoin transactions. Since this happens every day, on websites such as Coinbase, it should be overwhelmingly clear that this is neither [a] preventable nor [b] harmful to the Bitcoin cryptosystem.

- The Netural Scenario “N” was a thought experiment I suggested: what if the miners were, already -and in secret-, sending each other resource-intensive extension blocks? Miners could theoretically require each other to have an ‘optional extension block’ which was just 8 Terabytes of random data, every 10 minutes. In other words, they could be ‘required’ (by soft fork) to reside in a situation where they have the ‘option’ of keeping track of larger blocks. Since we, the outside observers, would only see a random, nondescript hash (somewhere) in (some) blocks, we would have no way of noticing if Scenario “N” had been adopted in the past, or not. It was admitted that this was also [a] unpreventable. The [b] harms couldn’t exist if the optional block had no net benefit (ie, new fees - new costs) to the miners who opted-in, but if the optional block had net benefits (and was popular) it could theoretically cause miner decentralization problems.

Hence the meaning of the complaint: it would be nice if the miners could opt-out of running a sidechain node while suffering no opportunity cost of lost transaction fees.

In other words: miners do none of the work, but they still get paid the tx fees!

As LOL! as this requirement is, I think I’ve risen to the challenge anyway.

Specification

Focus

Let me begin by highlighting these four facts:

- Drivechain already assumes that each full sidechain node is also a full mainchain node (ie, side:fullnode implies main:fullnode). This creates a stable, long-term link from the side:chain to the main:chain (even if it is not reciprocated).

- One or more sidechain-users (with full sidechain nodes), might happen to own (unrelated) BTC on the mainchain, purely as an accident of circumstance.

- Side:users will be largely indifferent between these funds (their 4 side:BTC vs their 4 main:BTC), but main:miners will not be indifferent – they will strongly prefer main:BTC. (Later, we will exploit the fact that main:funds have been ‘pre-validated’ by miners.)

- More specifically, we can define “v” as the “value” of a side:block, defined as (total txn fees of side:block - epsilon). A sidechain node might, at any given time, happen to own v quantity of BTC on the parent mainchain.

- Nodes, even if they do zero mining, can construct a valid block/blockheader, one where they pay themselves 100% of the transaction fees. Of course, this would normally be pointless, because there is no reason to expect the header to meet the difficulty target (without the node also doing a lot of hashing).

- Any attacker who is willing to pay v or greater, can already fill a block (with spam). Therefore we are, today, implicitly assuming that an attacker is never willing to pay v per block, to (temporarily) DoS the blockchain.

The Idea

With that in mind, we divide the labor, between a side:node “Simon” and a main:miner “Mary”.

- Simon (side:node) knows that side:block is worth v, and Simon also happens to own v worth of main:BTC. Simon wants Mary to include (“critical hash”) h* into a mainchain coinbase. If this is done, the side:block will be successfully merge-mined. If Simon can cause his block to be merge-mined, Simon can claim v worth of side:BTC.

- Mary the main:miner doesn’t know anything about anything on the sidechain, but she does have the ability to include things in mainchain coinbases (at almost no cost). Mary prefers having more money to having less money.

Therefore, the scheme is for the side:node to pay mainchain:v to the mainchain:miner, if and only if the miner will include h* in mainchain:coinbase. A side:node treats this h* as a found side:block, although if it violates any side:rules it may be later interpreted as invalid (or, as empty). Under many scenarios, (if the other nodes never receive any transaction data, or if any of this data is invalid), the block is likely to be orphaned by side:nodes as they build the heaviest valid side:chain. Therefore, Mary doesn’t need to know what she is including or why (one small exception, see “Problem” below).

The Simons of the world keep epsilon for themselves, which compensates them for running a full node, and for providing this service. As transactions fees increase in the current side:block, Simons can offer larger v’s to Marys. Since Mary will always seek out the largest v she can find, this will be a perfectly competitive market, and the epsilons will be as low as possible. This has the beneficial side-effect of giving all Simons a strong incentive to fee-maximize, when they assemble side:blocks. Moreover, Simons are punished for assembling invalid blocks – Simon receives zero for these, but still must pay Mary full price.

Each block which is merge-mined in this way, would count as meeting the sidechain’s “difficulty target”. In this way the mainchain would always be “in charge”, and there is less of a danger of the sidechain becoming “too popular for its own good”. This may also allow us to delete redundant data fields from sidechain-headers.

Enforcing this Smart Contract

This arrangement could be enforced with a new OP Code, which we might call “OP_is_h_in_coinbase”. This can be used to {pay v from X to Y} if h* was, in fact, included in a coinbase txn. This OP might require that Mary supply [1] a mainchain block header (or way of referencing one), [2] a path from the Merkle root of the header, to the coinbase txn in the header’s transaction set, and [3] the coinbase txn itself.

The op code would need to check

- That the header was in fact, included in the blockchain a=200 blocks ago (or whatever).

- That the path does link from the valid header to the coinbase.

- That the coinbase does, in fact, contain h* in the approprate spot.

As usual, through use of the lightning network, we can avoid ever actually needing to use this OP code on chain…it can all be off chain, unless (as usual) someone attempts to break the agreement. This is fortunate, because these txns are larger than average and we’d prefer not to broadcast them on-chain.

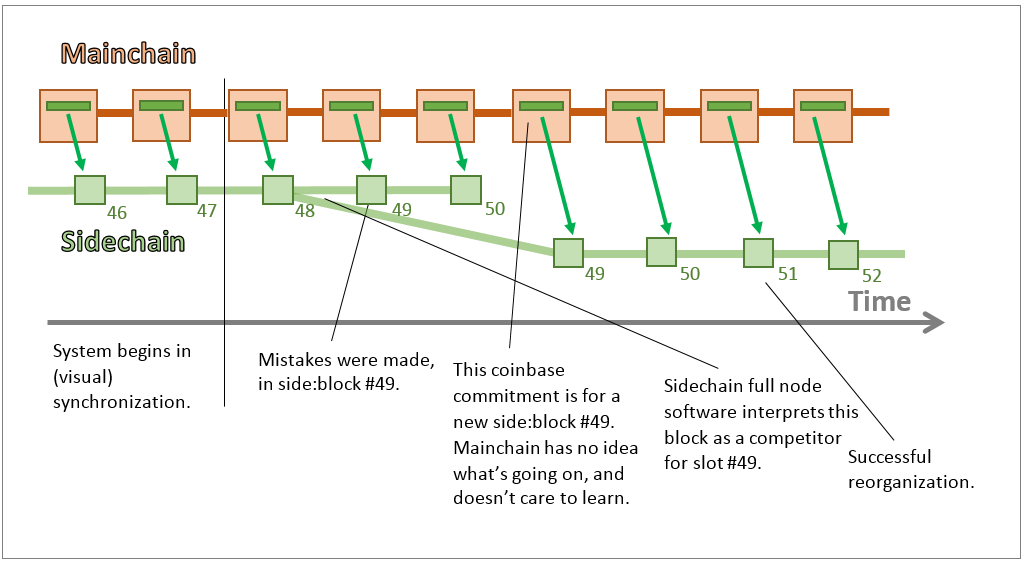

Handling Reorganizations

In pursuit of wisdom, we don’t want the sidechain to affect the mainchain at all. However, both chains need the freedom to reorganize.

For example, consider a “DAO sidechain” which encouters a critical bug, such that users want to reorganize the chain. Can we accomplish a rollback, without the parent mainchain being affected at all?

Yes, this is very simple:

If the DAO had been a Bitcoin sidechain under this scheme, developers could have rolled back the ‘DAO part’ only, without interfering with the Bitcoin mainchain or any other sidechains. No splitting of the chain, and (almost) everyone getting what they want.

( Except for the hacker, of course. And except for the contradictions inherent to not enforcing a clear contract (why make one at all?) or enforcing contracts arbitrarily. Plus I would never get my favorite video, nor would I have gotten to help The Big Man win Most Influential for Year 2016. )

Other Effects

Better SPV, Better Merged-Mining

As usual, SPV mode on the sidechain would require not only the side:headers, but the parent:headers, as well the “linking data” from each parent:header to each side:header. However, the side:headers would not need to be twice as large (as is usually the case). Many data fields are unnessary (as there are no difficulty adjustments), or have been moved to the “linking data” of each parent:header. This data is the following two items, for each parent:header: [1] the path from the parent:header’s hashMerkleRoot to the coinbase txn, and [2] the coinbase txn itself (or, proof that it contains h*).

Since side:spv-clients already must be main:spv-clients, the main:headers do not need to be stored an extra time. Therefore, this scheme increases efficiency of a sidechain’s SPV-mode (relative to a merge-mined Altcoin). Moreover, if there are many sidechains, the [1] path from header to coinbase, and [2] coinbase can be reused, resulting in greater savings.

Efficiency can be further improved with “pre-defined coinbase real estate”. Typically, merge-mining just “includes some data” in the coinbase, and hopes that the merge-mined nodes willnfigure it all out later. However, this type of merge-mining can impose (or assume) some structure on the mainchain coinbase. Each commitment can, then, contain sidechain-specific prefixes, such as nmc:6hyfli…, or hvm:s83lHe… . This can be done with a “light touch” – instead of enforcing the rules via soft-fork, sidechain nodes can simply ignore all-but-the-first included h* (of a given prefix). Or, we might use a predefined (and henceforth unalterable) sequence which maps some coinbase-bytes uniquely to each active sidechain (this would save even more space, but be less flexible).

Problem

One disadvantage to “blind merge mining”, is that if miners never validate sidechains at all, whoever bids the most for the chain (on a continuous basis), can spam a 3-month long stream of invalid headers, and then withdraw all of the coins deposited to the sidechain. Since the mining is blind, and the sidechain-withdrawal security-level is SPV, miners who remain blind forever have no way of telling who “should” really get the funds.

However, if a dispute arises, (about who “should” receive funds from a sidechain) miners can temporarily “upgrade to full node”. While before they ran no sidechain software, now they (temporarily) become a full participant. Such an upgrade is time-consuming (miners must run this software, allow it to determine the location of all headers, all of the data in each of the header’s blocks, and the validity of this data) but miners have a long time (months) to do this. They thus determine the heaviest valid chain, and thereby resolve the dispute. It is essential to note that dispute-resolution is only necessary while there is a legitimate “dispute” – if hashers trust their pool operators, and the pool operators trust each other, then, in practice, the dispute can be resolved with just one or two additional nodes.

Therefore, there is an inbult mechanism in place for resolving any disputes in an objective and cryptographic manner (ie, without trust). And because it is so effective, it is unlikely to be needed or used.

Does anyone care?

I expect miners, in all cases, to just run the sidechain nodes. In other words, I don’t think miners will actually care about this idea, “blind merge-mining”, enough to use it. This is because the marginal cost of “sighted mining” is already very low –just more software.

Of course, once the side:node is on, there may be an additional incentive to upgrade to a data center, which bothers some people, hence this post. This incentive is a situation of variable cost, no different from an incentive to purchase additional ASICs (or to purchase them in large marine-sized containers). In fact, in our optimized world of SPV and SPY mining, one could argue that this proposal is bad for mining: by allowing miners to include transactions without ‘paying’ their bandwidth cost, we are encouraging miners to include transactions without verifying them. Ironically, this also doesn’t bother me at all, but it tends to bother the same people who are bothered by data centers! Some people you just can’t please!

Or can we? After all, miners are free to move between the ‘blind’ and ‘non-blind’ versions as they wish (by declining to run, or choosing to run, their own full nodes). So, when ~complainants are in a datacenter-phobic mode, they can use blind merge-mining, but when they decide that they care about validation, they can validate in the traditional way (by running a full sidechain node). Therefore, even inconsistent people can be in a constant state of happiness (or unhappiness, I suppose).

Conclusion

I’ve presented “blind merge-mining”, which exploits the economic relationships between a parent chain and its sidechain, to make the merge-mining process leaner on both sides. A sidechain’s nodes do everything that miners would normally do, and then bribe miners to ratify their side:block. The bribe takes place on the mainchain (which, incidentally, is why this maneuver is impossible on the mainchain – it requires one ‘normal’ chain to already exist).

Updates

Two notes:

- Function specifications.

- A design note on maximizing side-to-main throughput.