Some users need the unique properties of Bitcoin. Others will just use whichever payment-system is cheapest.

The “market for Bitcoin block space” is a hot topic. Everyone’s talking about “blocksize” and “fees”.

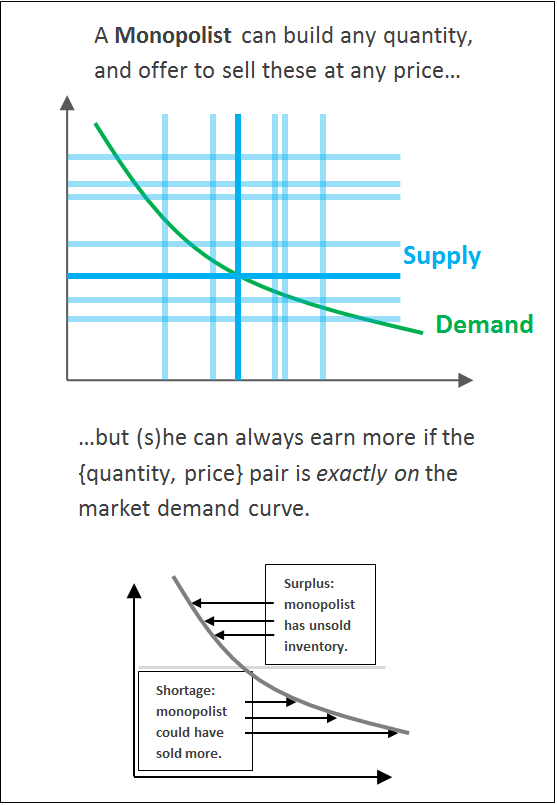

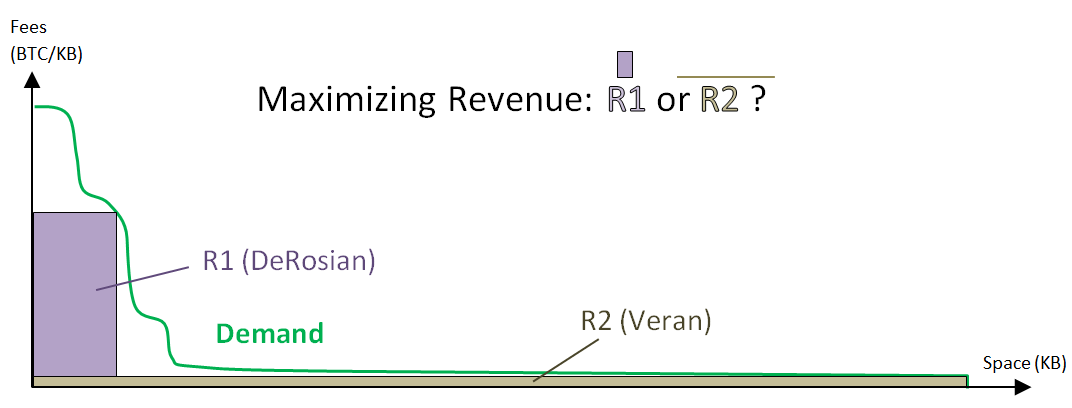

Economists frame these issues in terms of “supply and demand”. I’ve previously argued that, when it comes to blocksize and fees, miners will act as a single coordinated monopolist. This monopolist will select a point on the blockspace demand curve which maximizes total revenue. Gavin made a similar point a long time ago.

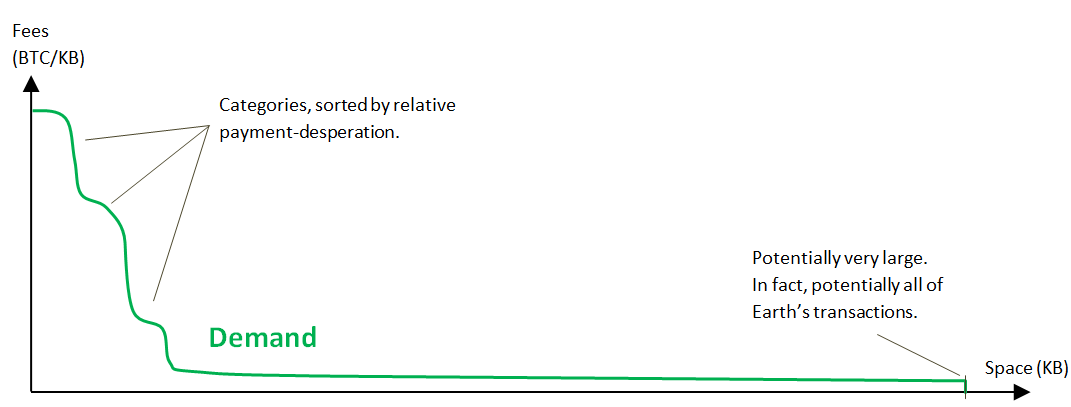

If this theory is correct, then the entire conversation hinges on just one thing: the demand curve. Where does it come from? What characteristics does it have?

( Speaking literally, of course, any demand curve is defined by the moment-to-moment whims of every person on the planet. But what generalizations can we draw, if any? )

The Two Types

I think we can separate Bitcoin demand into two categories: inelastic (“needs Bitcoin”) and elastic (“doesn’t need Bitcoin”).

The inelastic demand I will call DeRosian demand, after Chris’ interviews with these Bitcoin-customers.

Bitcoin has a monopoly on these types of payments, be this for:

- legal reasons (online drug sales, ransomware payments, tax evasion, gambling, hiding assets)

- privacy reasons (pornography, HIV-test)

- technical reasons (ie, “smart contracts” such as multisig, pay-for-data, pay-for-document, pay-for-wifi, etc which we might further specify as “Szaban Demand” after Nick Szabo).

For these payments, traditional systems cannot compete with Bitcoin, and Bitcoin users will therefore tolerate a higher price. This leads to certain stories…for example of desperate users who pay cash bribes to restaurant-owners and/or security guards in exchange for (after-hours) access to a Bitcoin ATM (now!).

In contrast, the elastic demand I will call Veran demand, after Roger Ver who is presently focused on making Bitcoin transactions as cheap as possible. Veran users just want to transact the same way they’ve always transacted…but at a cheaper price. These users have no loyalty to Bitcoin specifically, they are only loyal to their pocketbook.

Are Bitcoin Transactions Cheap?

It depends.

“Veran demand” simply refers to a type of demand – something that users could want. And users almost always want cheaper prices.

The question of whether we can actually meet this demand, is another matter. Nonetheless, I address the issue in this section, to show that it is not categorically impossible.

( And also, we could quip that the Veran Philosophy “demands” that the Bitcoin network take one shape, whereas the DeRosian Philosophy “demands” the network to take a different shape, as we will see. )

Bitcoin Transaction Efficiencies

Bitcoin has two inherent cost-advantages.

The first is infrastructure: Bitcoin is “lean” relative to credit cards and banks, because Bitcoin does not need to pay for employees, brick-and-mortar buildings, swipe machines, data cabling, proprietary software, customer service departments, etc. Instead, Bitcoin relies on the user to bring their own hardware / software / connectivity (internet access) / operating expertise etc. Most of these, the user already owns, or can obtain at no cost. The savings are particularly evident at the international level.

The second is fraud: traditional payment systems socialize the cost of fraud, by [a] forcing each customer to pay a little more, and [b] reimbursing customers who are defrauded. Instead, Bitcoin avoids the surcharge completely, but gives users full control –and full responsibility– over their funds. This, in turn, cherry-picks the users who are most able to manage their own cryptographic affairs, leading to greater efficiency system-wide.

Along this theme, BitPay allows merchants to accept their customer’s Bitcoin…swapping it for a cheap, fraud-free cash deposit the next day. Purse.io lets Bitcoin shoppers save an incredible 15% or more, by taking advantage of inefficiencies in Amazon’s ‘store credit’ payments system.

The Global Broadcast Network

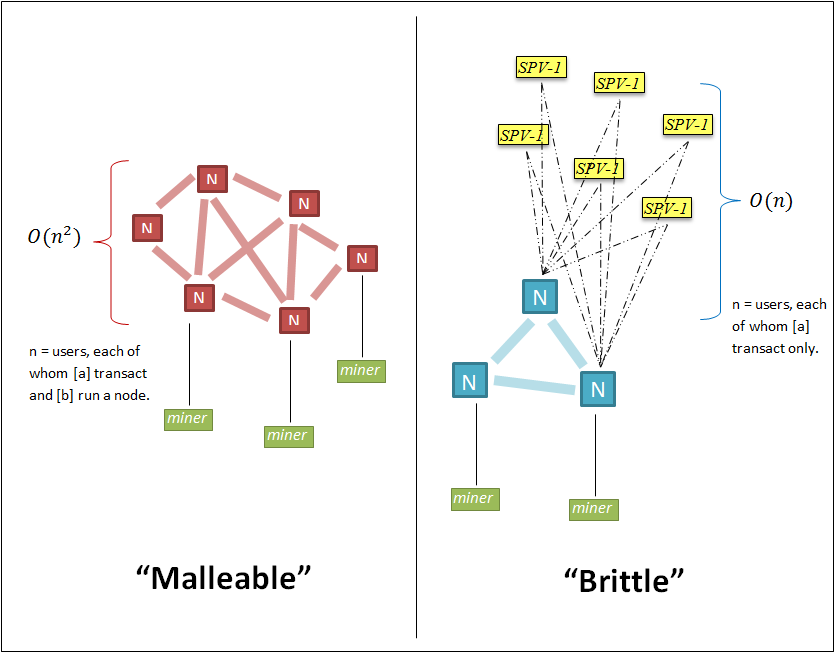

Some readers may immediately be protesting my claims of efficiency. After all, is not blockchain a very inefficient broadcast medium? Is it not a slow global mesh network, O(n2) scaling, that must shamble on at the pace of its slowest members? Is it not more like a low-bandwidth smoke signal than a printing press?

Well, it depends!

On one hand, a paranoid user would need to run their own node. They would only “know” that they had really been paid by checking all of the data in all of the blocks, to make sure it was following all of the rules. This currently requires the user to commit computational resources: roughly ~100 GB of hard drive space, several days worth of CPU time, and a significant chunk of bandwidth.

In contrast, a user might rely on SPV mode, in which case the user can assume they’ve been paid if [1] they have been provided with a Bitcoin transaction which [1a] pays them, [1b] is appropriately formatted and [1c] has inputs / Script which are not-invalid, [2] this txn has been included in a block, [3] this block has been built on (ie, 6 or so confirmations), and [4] the blocks all contain sufficient work. Meeting these requirements, only requires a paltry 4 MB of space per year, and almost no computation, and it does not encounter the O(n2) scaling problem (more below).

The designation of the two configurations as “malleable” and “brittle” is appropriate in two ways. Firstly, the spv-connections are easier to damage, and if damaged they can break completely. In contrast, the malleable connections can be struck with tremendous force and the network will mostly be unaffected. Secondly, it so happens that gold is the most malleable of all Earth’s metals, and the ‘malleable configuration’ more-resembles a network of digital gold. In contrast, the brittle configuration more-resembles a traditional payment system – one where you trust a database maintained by someone else.

Security Model

One metaphor for decentralized, P2P blockchain is Montesquieu’s tripartite – a form of government designed to resist tyranny by “separating” its powers (and thus minimizing the quantity of total power granted to any corruptible individual). In Bitcoin’s case, the “legislative” power (to write the laws) rests with the developers, the “executive” power (to remove unlawful activity from the network) rests with nodes and miners, and the “judicial” power (to decide if the laws are truly being enforced, as written) rests with each individual user, who is always free to resolve a dispute by running a full node and checking everything for themselves.

The malleable-focused users claim that everyone needs to run a full node, else they are vulnerable (to theft, and to loss of privacy). The brittle-focused users are more comfortable with the idea that nodes can be run by other people, namely specialists. If enough specialists exists (or, more precisely, if barriers to entry are low), competition will hold the system in line.

Thus, there is a disagreement over the requirements of this “judicial branch”. Some, such as Luke-Jr and Peter Todd, want it to be accountable to every user, personally. Others, such as Gavin Andresen, are satisfied with the judicial branch merely being “sufficiently accountable”.

( Satoshi’s whitepaper advances the latter view, supposing that, in steady-state, only “Businesses that receive frequent payments” will run a node. However, he later added a blocksize limit in July 2010, supposedly after Hal Finney convinced Satoshi that the limit would help nodes survive DoS-attacks. While Satoshi understood how to make the limit temporary, he instead chose to make his limit permanent. He later chose never to remove the limit, and never to change it to a temporary one. And he ultimately chose to leave the project, in this state. With no other information to guide me, I can only assume that all of these actions were intentional, and that Satoshi originally took the brittle view in earnest, then switched to the malleable view, but that he overall felt very confused, and ambivalent about both view. My conclusion is that Satoshi simply didn’t know which was right – or, at least, that his knowledge then did not significantly surpass our’s today. )

Cost of Security

Bitcoin users pay transaction-fees to get their payments processed. These “taxes” support the government, but for technical reasons they can only support some of the government. These payments go to the miners, but not the nodes. The support the police officers and the army, but not the courts.

This leads to a crucial full node externality, which is O(n) if n=transactions, as you must store all of other people’s transactions. If user-growth is itself geometric (as it usually is), we will have u=time^2 users over time, which will cause the externality problem to become unsustainable.

This externality-cost is far higher than a user’s transaction fees. In fact it will likely always be higher than the entire cumulative sum of all transaction fees paid by everyone.

Here’s the crucial point: in SPV-mode (ie the “brittle mode”), you don’t have to pay the externality cost at all. The externality problem scales O(1) and so your total costs are O(n).

Promotion Strategy

Finally, the two views offer different advice on how to promote Bitcoin.

DeRosians advocate a vigilant defense of Bitcoin’s decentralization and censorship-resistance, hoping to “outwit, outlast, and outplay” rival currencies and payment-systems, by waiting for rivals to self-destruct. Verans try for offense, favoring an “Uber strategy” of blindingly-fast popularity, so as to simply outrun obsolete/corrupt regulatory hurdles (and become politically-acceptable sooner).

As is usually the case, one approach is ‘conservative’ (slower, but less likely to end in disaster) and the other is ‘liberal’ (riskier, but with more-effective results, sooner). If the unknown risks are great, then the DeRosian approach is imperative. If the risks are small, then the DeRosian approach is pointlessly prolonging human stagnation and misery.

Equilibrium Market Behavior

Fee-maximizing miners might be genuinely unable to decide which demand-type they are in, or even which they would prefer. For them, it would be best to capture both types via price-discrimination.

Below is a representation of this conjectural demand curve for blockchain broadcast space, given the two categories of demand:

And below this are the revenue-maximizing (fee,size) selections, for each demand-type in isolation:

Either of the two selections might maximize miner revenue (R). In fact, over time we might actually switch back-and-forth between the two.

Ideally, the highest total R might be achieved by maximizing each of the two demand types separately (a kind of price discrimination) and adding them together. This is only possible if [1] there are two networks, and [2] the DeRosian group can be discouraged from using the cheaper (Veran) system.

This might, in fact, actually happen – a LargeBlock sidechain would fulfill both requirements, as it would [1] create a second network with [2] higher full node costs (and, possibly, more stringent KYL/AML controls). And, despite an algorithmic 1:1 peg, DeRosian coins may be permanently more expensive in the spot market, due to the speed and inconvenience of transferring coins from a sidechain back to the mainchain. Specialist banker-types may charge a few basis points for on-the-spot lightning-network settlement. In turn, this cost would further discourage the groups from mixing, and may allow miners to price-discriminate.

(Obviously, the DeRosian world prefers to keep centralization (ie, CONOP) low, and is willing to force transactions to be more expensive. The Veran, in contrasts, prefers transaction costs to be low, though this consumes more node resources.)

Synergy

While the two demand-types are different, they are also mutually reinforcing. Each contributes to the underlying network: DeRosian transactions provide fundamental value, and shield the network from panics; Veran transactions provide plausible deniability, which greatly complicates prohibition efforts. And “The best defense is a good offense”, as they say.

Parting Words

Contemporary Bitcoin seems to occupy a compromise position between these two worlds. Perhaps, we are trying to meet both types of demand?

A 1 MB block may seem small, but as there are ~1,000 blocks per week, the true figure is 1 GB (per week). This is simultaneously [1] very high (relative to the typical desktop applications), and certainly high for TOR, but also [2] remarkably low (relative to a professional payment processors, whose quarterly operating expenses are X00 million USD).

comments powered by Disqus