Abstract

An ultra-simple, but extremely effective wallet-side Bitcoin privacy tool: sending your coins to yourself, in a way that makes it look as though you are sending them to someone else. Every wallet should have this tool!

I. Intro

A. Pros and Cons

Deniability is a simple tool that makes it very easy to “shuffle” your coins (ie, send your UTXOs to yourself). After running it, it will look as though all of your BTC has been sent away to other people (when in reality it remains with you). In other words, Deniability allows users to claim –credibly– that they own no Bitcoin.

The downside is that we must mix in “fake” transactions together with each “real” txn. Therefore, extra blockspace is consumed, and extra txn fees must be paid.

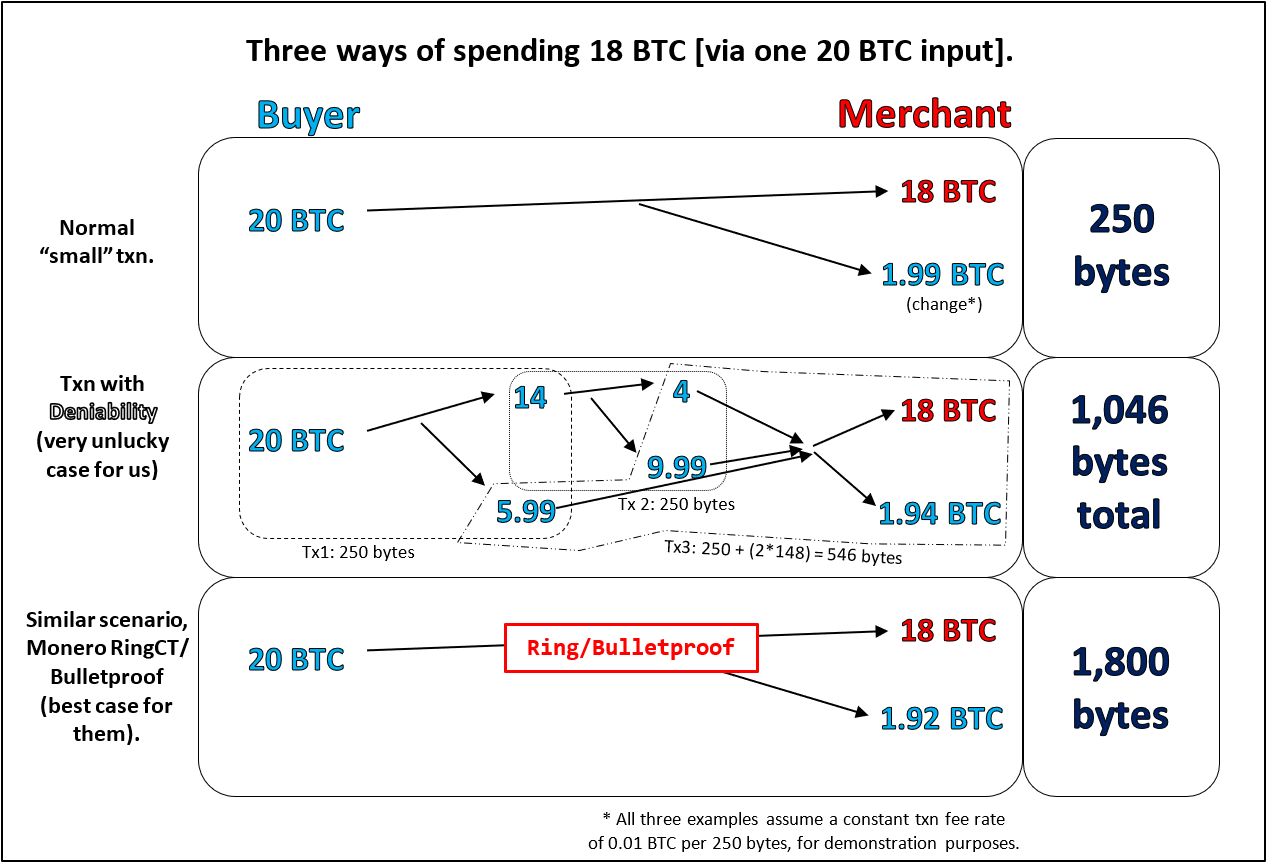

One way to think about it, is to imagine that “deniable” transactions take up roughly three times the size as regular txns (as they’d require, on average, two additional “dummy” txns). This triples the blockspace required, from about 500 bytes total (for one modern transaction)1 to 1500 bytes total on average. This is actually quite competitive – for reference, Monero’s brand new, state of the art, ultra-private bulletproof txns each require 1800 bytes2 in their absolute best-case scenario. So if we take that to be the industry standard, Deniability is still actually ~17% smaller.

A further downside is that user’s funds are spread out over many more UTXOs than they would be otherwise. Thus, in order to spend the same magnitudes, the deniability-user must be prepared to make larger txns down the road.

However, if we again compare the best-case 1,800-byte Monero txn to a worst-case “Deniability clean-up” txn, (one which has been split twice, and whose three outputs must unfortunately be recombined in a third txn) the total byte cost is still much lower.

See here:

This is because each BTC input requires only 148 bytes, which is extremely small compared to Ring/Bulletproof’s total size of 1800 bytes.

So, relatively speaking, the costs are negligible. On a “payments” blockchain, such as the BCH network or a largeblock sidechain, the costs [to the transacting user] are almost nonexistent.

B. Unique Properties

This idea presented below is…

- Very simple – Absolutely no new cryptography, soft forks, security assumptions or new complicated math. Does not mandate a single implementation. Practically as “bug free” as any design can realistically be.

…but despite that, it has several interesting properties:

- Unilateral – Deniability increases a user’s privacy, even if he/she is the only user [of deniability]. To my knowledge, no other blockchain-privacy-system has this property. In fact, Deniability is so non-interactive that it only barely requires an internet connection at all (at the very end of the process). You are mixing with all of the other users of the blockchain – whether those users want to mix with you or not!

- Meta-Private – Deniability not only allows the user to “deny” that they own any BTC, but it also allows the user to “deny” that they are using Deniability! Even when you are using it, it looks [to all observers and counter-parties] exactly as though you were not using it. Again, this property is very rare – for example, on BTC, neither “ring signatures” nor “confidential assets” nor “zk-snarks” would have it.

- As-Needed – Use of Deniability can vary with the need for privacy. Those in dire need of great privacy (such as political activists3) can make use of the process multiple times, increasing their privacy with each use. Unremarkable people, in contrast, can Deniabilize their UTXOs just once, or not at all.

The second property is crucial. Without it, we have a so-called “unraveling market” and no useful privacy. Ideally, it is achieved when someone invents a technique that is both cheaper and leaks less information (thus drawing in the “mainstream” users, so that the “stigmatized” users can freely intermingle with them). Unfortunately, these miraculous “cheaper AND more private” breakthroughs are very rare. Even worse, they violate the 3rd property (“cheaper meta-privacy” is inconsistent with “as-needed privacy”).

The first property is also quite useful. Interaction (of any kind) always opens the door to harassment – an adversary can join the set of interacting members, but fail to interact properly. It also opens the door to surveillance: many “mixing processes” (such as the “Coin Shuffle” – now default in Electron Cash) require real-time message exchange over the internet – adversaries may be able to observe this traffic. Worst of all, CoinShuffle breaks completely if the attacker Sybil attacks it (ie, connects to you pretending to be “many” “other” people for you to mix with).

C. Previous Work

Before I continue, let me say that “Deniability” is a very simple and very old idea, that many people bring up from time to time. It does nothing “new”, it is merely a collection of “wallet-side” tools to make the shuffling process easier (ie, less labor-intensive, and with less potential for error).

I believe that it is profoundly under-appreciated. It is very effective and very easy, and painless to implement.

If so easy and useful, why don’t have it already?

Well, it is probably due to two stigmas: [1] the sigma of “wasting” block space4; and [2] the stigma of working on a privacy technology that is non-mathematically impressive and ostensibly uncreative.

II. How it Works

A. Basic

Here are the steps that Deniability performs:

- User “Alice” selects a UTXO to be “Deniabil-ized”. This UTXO is the “target UTXO”.

- [Optional] Software queries the blockchain for “what most transactions look like these days”.

- Software constructs a txn that sufficiently “blends in” with the rest of the blockchain, but which spends Alice’s target UTXO. The outputs of this txn (the new UTXOs which are created) are all still owned by Alice.

This process is then repeated an arbitrary number of times. Alice can “Deniabilize” every single one of her UTXOs, as many times as she likes. She can even (and occasionally should) Deniabilize UTXOs that she has just Deniabilized.

You see? Very simple.

B. Advanced

We can (and should) make the tool much better in a few ways:

- By default, Deniabilize UTXOs a random number of consecutive times. Use some kind of survival function to determine when to stop Deniabilizing each UTXO.

- During txn broadcast, mask the fact that all of these txns were created by the same computer. This should involve several steps:

-

- Use TOR/I2P/VPN to connect directly to a miner’s mempool.

-

- Do not broadcast all the txns at once. Instead, have your wallet software hold on to them a random amount of time before broadcasting. [Optional] sample this randomness from known “real” transaction broadcast times (ie, concentrate the broadcasts during the daylight hours in London, NYC, Tokyo, etc).

- Automate the process as much as possible, in general. Even turn it on by default.

- Minimize the user-effort required. Construct all of the txns at once, and then have the user sign them all at once. For users with an air-gapped setup, save all of the txns to one file, and allow the signed versions to return via a stream of QR codes – have the “hot” computer know exactly how to interpret them (ie, how to save them txns to disk and then broadcast them at a random time).

- Track and store the Deniabilization status of all UTXOs. Warn users if UTXOs have not been Deniabilized yet.

- Enable “right sizing” as an option for Deniability. “Right-sizing” is preemptively creating an output that is just the “right size”. For example when you anticipate the need to spend $5 with a $0.04 fee, you might make an output containing exactly $5.04. When you spend this output, there will be no change address5.

- Have volunteers run a free service where they report blockchain “summary statistics” in a concise way. In this way, even lite clients can easily learn what the typical recent txn is like. This could include the median and mode of the following:

-

- Txn size in bytes.

-

- Absolute number of inputs and outputs.

-

- Heterogeneity in output magnitudes (eg, These days, is all of the txn’s BTC getting allocated to just one output (ie, “right-sizing”)? If not, how does it tend to be distributed across its outputs?).

C. Going Even Further

So far, we’ve assumed that the attacker is watching the blockchain, but has NOT gotten his hands on anyone’s wallet.

As a result of that assumption, it does not matter if Alice’s wallet software explicitly tracks, and stores, the Deniabilization history of her UTXOs. In fact, this greatly improves the user experience.

Clever Bitcoin users will keep their private keys on a “cold” medium (eg, an air-gapped machine, a hardware wallet, pen-and-paper, etc). They will pair that device with a “watching only” wallet (a “hot” wallet which is connected to the Internet). The hot wallet can create and monitor transactions, but it cannot move funds because it cannot sign transactions.

Obviously if an adversary finds the cold storage, it’s game over – they can find all the funds and steal them.

But what if we want “Deniability” to work well, even in cases where the “watching only” wallet is found by the adversary?

We could:

- Encrypt the transaction history of “watching only” wallets.

-

- Prompt the user for a decryption password upon every login. If the user forgets this password, they can still restore their wallet using the original seed (the private keys) – they will get all of their money back upon re-importing these keys.

-

- Have a “duress” fake passcode show zero transaction history, or have it show a fake history (similar to the “inner volumes” used by TrueCrypt/VeraCrypt).

- Periodically back up the accounting data, to some different medium (flash drive, air-gapped computer etc). And then delete the accounting data from the “hot” computer, of course.

III. Privacy Discussion

A. The Basic Privacy Problems

The core privacy issues with Bitcoin’s UTXO model are:

- After Receiving: Your employer will be able to see whether-or-not you’ve spent your salary, and when. And probably (to some extent) what portion of your salary has remained unspent.

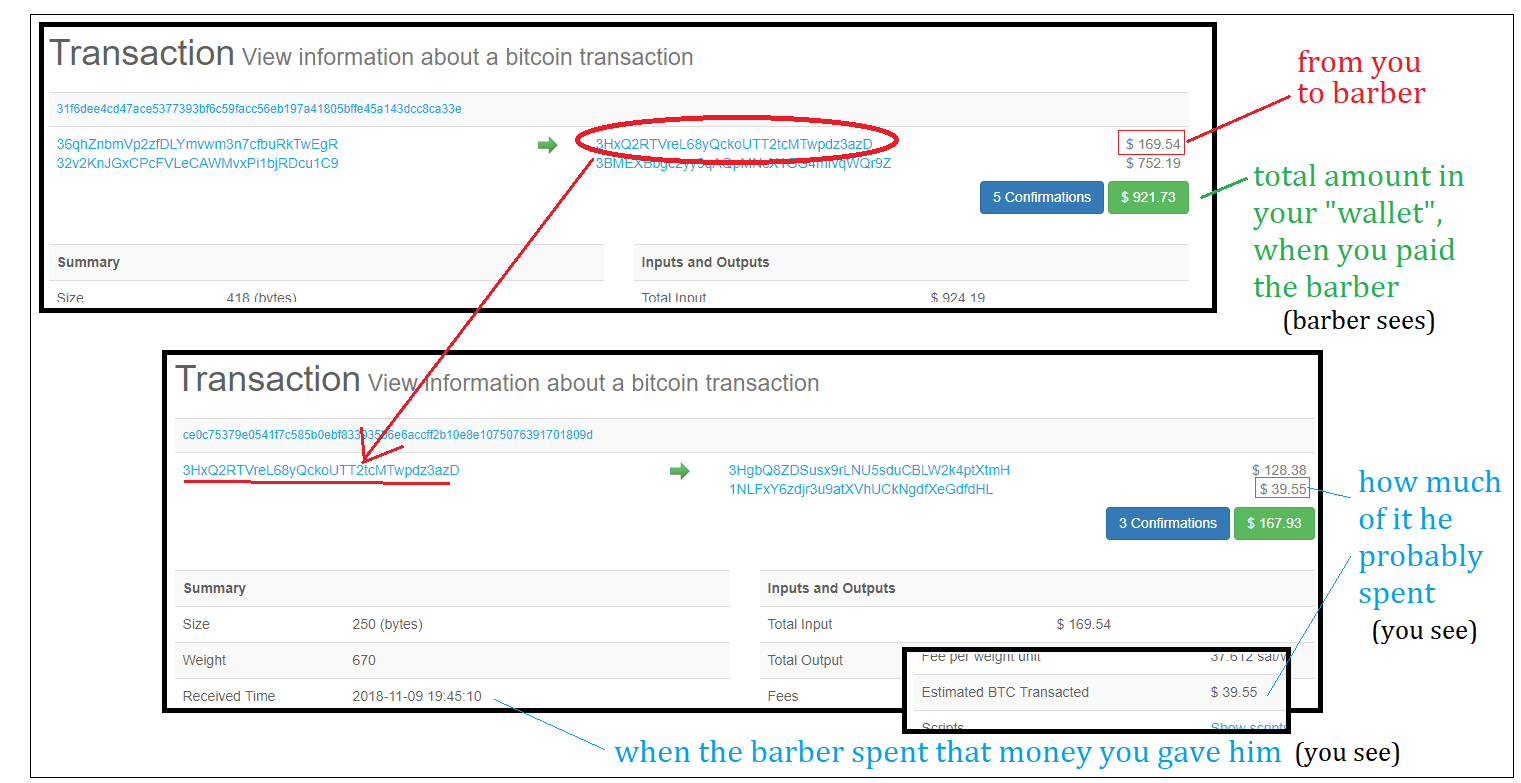

- After Spending: Merchants can learn extra information about the net worth of their customers. Eg, your barber can very easily learn how much money was in your “wallet” when you opened it up to pay him for your haircut.

Deniability addresses both issues. First, upon receiving money, you can mix with yourself immediately an unlimited number of times. Your employer will not know how much of your money has “actually” been spent and how much has merely been “Deniabil-ized”. Second, immediately before a purchase, you can use Deniability to make a “right-sized” output (one which is exactly the size that you want to spend) – in a sense, you’ll be able to give your barber ‘exact change’.

B. The Flow of Information

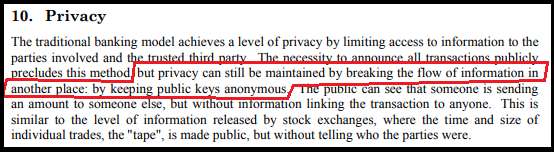

Satoshi laid out a specific privacy model for Bitcoin. Instead of blocking the visibility of the txns themselves, it involves “breaking the flow of information in another place”…

…specifically breaking the relationship between “public keys” and “individuals”.

But what I set out to do here is more like the original (traditional banking model) plan: to break the visibility of “actual economic transactions” …by breaking the relationship between those and the (observable) on-chain blockchain “transactions”.

C. Example

Imagine that Alice and Bob are known associates, and they each of them may be users of Deniability. Further suppose that a “chain analyst” already knows that UTXO #345 belongs to Alice.

Finally, let us assume that the blockchain grows, and that the new blocks contain exactly four new transactions:

- A txn which spends #345, and creates (#346, #347).

- A txn which spends #346, and creates (#348, 349).

- A txn which spends #348, and creates (#350, #351, and #352).

- A txn which spends spends #347, and creates #353.

Here below, I show the individual TXOs as numeric values, and the transactions as multi-pronged arrows connecting them:

#345 ----> #346

\ \------> #348 ----> #350

\ \ \----> #351

\ \---> #349 \-----> #352

\

\--> #347 ---> #353

In a world with Deniability, what can the analyst conclude from this information?

Well, it is possible that all five of the surviving UTXOs (#350, #351, #349, #352, #353) actually belong to Alice. This would happen if Alice Deniabilized #345, and the randomization software buried that output beneath four “layers of deniability”.

But it is also possible that four of the five UTXOs belong to Bob. Alice may have “right sized” output #347 so as to pass Bob just the right amount (#353) in txn four. Txn two may have been a second “real” payment to Bob, with him obtaining output #348 (which he later deniabilized in txn three). Alice owns #349 (and Bob owns the rest).

Or, perhaps #349 is not what Alice owns at all. The txn in which Alice paid Bob could instead have been #346. In which case #347 would be Alice’s change. Then Alice performed a simple deniabilization, sending all of #347 to herself. So Alice owns #353, and Bob owns the rest (which he deniabilized).

Or, Bob could own just one of the UTXOs, #349, and Alice could own the rest – the exact reverse of the example two paragraphs ago.

Or, we can recast the second example in yet another way. Imagine that #346 is Alice’s change from a “real” first purchase, and that #349 is her change from a second “real” purchase. Alice still ends up owning only output #349, and yet she hasn’t touched the Deniability option once. It was Bob who did all the Deniabilizing! This is an example of the “meta-privacy” property. And of course, a reverse stories are possible where Bob never used Deniability and only Alice did.

Consider how effective this technique has been, even on the scale of this absurdly oversimplified toy example. We started with the adversary knowing everything – specifically, that UTXO #345 was owned by Alice. But just four transactions later, and the adversary now knows basically nothing: first, he knows that some, or all, or none, of the value of #345 might have been directed to Bob. If we expanded the example to include Carol, the adversary would know even less. And, in the real world, this “example” would not be limited to Alice/Bob/Carol …it would include everyone on Earth.

C. Further Meditations

In general, these two types of txn will always resemble each other, by design:

- Innocent people making “private” txns (txn that do not go through KYC/AML process, such as reimbursement for drinks among friends).

- Truly paranoid people who are Deniabilizing every UTXO they possess.

The two will resemble each other in every way, if Deniability is configured correctly. And so there should be effective mixing between the two.

IV. Lite Clients

Do any lite clients randomly query full nodes for random transactions (ie, random regions of blockspace)? This would help user to “deny” that they actually own any of the coins they are asking about. In fact, the mere presence of this option may be sufficient to give considerable “deniability”. It needs only to be on by default, and located in a very popular piece of software.

Conclusion

Deniability is a very simple idea, that probably helps user-privacy substantially and at very little cost. It is easy to code, especially for “normal” (non-blockchain) developers who are used to caring about UI/UX, and used to having the freedom to implement something however they choose, and in a way that can constantly improve over time by getting user feedback.

Footnotes

-

See this reference, stating that BTC transactions are now about 500 bytes. In practice, many Deniability Txns are likely to be “basic style” txns (1 input, 2 outputs, P2PKH), which would actually allow them to come in at the very low end: around 250 bytes. ↩

-

From this block explorer, one can see that (the very small coinbase txns notwithstanding), transactions are always at least 1800 bytes. See also this StackExchange answer stating that Monero txns were ~2,000 bytes in 2016, but later grew to about 13,000 bytes with the adoption of RingCT before shrinking by “approximately 80%” (which would place them at “about 2.5 kb”). ↩

-

By the way, have you ever wondered about where all of our laws come from (the presumably “bad” laws that “good” activists would oppose)? In the US, they are written by Congresspeople – mostly lawyers by training. But where do lawyers come from? How are they made? A famous Duncan Kennedy essay has some insight into this mysterious process, one in which deference to a hierarchy plays the dominant role. Privacy can help such a system better approximate a meritocracy. ↩

-

This one would be especially paradoxical. Because the adherents of this “we must protect the scarce precious block space” view, are the same people who adhere to the “settlement network” / “block space is a special, prestigious commodity for which the user should be willing to pay dearly”. In other words, the small-blockers are the people who tolerate high fees but greatly desire privacy. But Deniability allows users to freely make exactly that tradeoff; Deniability allows fees “per private transaction” to go up (…while also preserving the option for other users to use Bitcoin in a cheaper, less-private way). ↩

-

(Update 3/2020) Some have asked me about how “right-sizing” helps with privacy. First: adversaries tend to assume that, if the blockchain contains txns with just one output, then these txns are “self-sends”. By altrustically paying one extra txn-fee upfront, you shatter this assumption. Second: right-sizing will prevent the merchant from learning anything about your net worth. Without right-sizing, they will know that you owned all the txn’s inputs; but right-sized, you can claim that someone else happened to coincidentally give you a conveniently-sized output, some time before making your transaction – they may suspect that you are lying, but they have no way of proving it. ↩