Abstract

A replay protection strategy that minimizes multifactor competition during hard forks. UTXOs start as being identical and replayable, but “gradually” become separated and unreplayable. Users running the new hardfork get replay protection, but users running old software do not.

GARP stands for “Gradually Activated Replay Protection”.

(Although, if you want to imitate “UASF” and call it “UARP”, I guess I won’t complain.)

A. Reminders

- Transaction replay (TR) is the phenomenon where a user accidentally moves funds on other blockchains. User creates a txn on one blockchain, but –unbeknownst to them– this txn can easily be included in other blockchains. On all blockchains containing this txn, the inputs of the txn will be destroyed, the outputs will be created, and the txn fee will be collected by a miner.

- Replay protection (RP) is the act of preventing transaction replay.

- Historically, hard forks have answered the question of “replay protection” by turning it on or off. BCH turned it on, for example; SegWit2x (never implemented) left it off.

For any pair of blockchains, I will define a txn as either replayable or non-replayable:

- Replayable txns can be included in both blockchains – they have no replay protection.

- Non-replayable txns can only be included in one blockchain – these have permanent replay protection.

When broadcast, a non-replayable txn will split its input UTXOs. In contrast, a replayable txn will will [tend to] march the UTXOs – though on different chains, the coins will move from the same origin to the same destination.

Above: Two ballroom dancers move in the same direction (promenade). From wikipedia.

When “replay protection” is “on”, all txns are non-replayable and the entire UTXO set is split immediately. When replay protection is “off”, all txns are replayable and the UTXO set tends to remain identical over time, until entropy [sourced mainly from newly-made coinbase UTXOs] gradually disentangles the UTXO sets.

If txn replay were perfectly achievable, it will be difficult to say that “two” separate coins actually existed at all. One “coin” would be more like a “block explorer” of the other.

B. Gradual Activation

With GARP (Gradually Activated Replay Protection), each txn has both a replayable form (valid on both networks), and a non-replayable form (valid only on the newer network). Txns default to using the replayable form, until they download the hard fork software, at which point their coins are split upon the next spend.

C. Basic Advantages

The purpose of this setup to help the new network (“NewNet”, governing the “NewCoin”) compete with the existing network (“OldNet”, governing “OldCoin”).

Specifically, GARP actively accommodates three groups:

- Miners – Transaction Fees on NewNet (payed in NewCoin) will always be at least as high as they are on OldNet.

- Nervous Audience Members – Transaction volumes on NewNet will always be at least as high as they are on OldNet.

- Indifferent Users – Users maintain equivalent OldCoin and NewCoin balances, even if they buy or sell after the fork. So it does not matter if the user is inattentive during the fork (or on vacation, hungover, etc) – their post-fork purchases will still be brought along for the ride. So users no longer need to drop everything and research a fork as soon as it is announced. It is only later, after it is “too late”, that their buying/selling may leave them transacting on only one network. Their coins are not split until after the “economic majority”’s coins are split.

These features are absolutely crucial because of coordination anxiety – the self-fulfilling fear of a coordination failure. Coordination is a flavor of multifactor competition, and one of society’s most challenging problems – in fact, it is the very problem that blockchains were invented to solve in the first place!1 When replay protection is on, users are thrust into what is essentially a big prisoner’s dilemma – users may want to switch from OldCoin to NewCoin, but they know that if they switch alone they are doomed.

Above: Adolf Hitler announces “peaceful” annexation of Austria. Reichstag, April 1938. From this site.

Switching is best done with many other people simultaneously. This is exactly what GARP does. At first, when “most people” (ie, “the economic majority”) are undecided, GARP makes all the passive (“indifferent”) users into actual, full, transacting, fee-paying users of both networks. But later, after “most people” have decided to support one network or another, GARP will automatically kick users txns onto only the network whose software they are using.

With GARP, indifferent users are truly indifferent (they do not affect they outcome); and splitting is very user-friendly and easy (its automatic, in fact). Without GARP, indifferent users count as votes for the Old Network only (much like how the Soviet Union would count missing/blank ballots for the Communist Party by default); and splitting either happens all at once (with mandatory full RP) or else is very cumbersome (with zero replay protection).

| Type of RP | Indifferent Users Counted Properly? | Is is easy/possible for speculators to choose a side? |

|---|---|---|

| Full Mandatory Immediate | No | Yes |

| No Replay Protection | Somewhat | Somewhat |

| GARP | Yes | Yes |

But GARP has one final key advantage: it effectively forces exchanges to list the coin.

D. Exchanges

i. “Win Brian Armstrong’s Money”

(With apologies to both Ben Stein and Brian.)

In crypto, its always nice when an exchange lists your coin. It grants liquidity to the coin and validation to your project. And you get lots of visibility, as well.

But there is something even better than having the coin get listed. It is: when the exchange gives you FREE MONEY! And then eventually lists the coin anyway!

Yes, if you’ve recently installed a GARP-enabled chain, then you are actually hoping that the exchange does NOT list the coin. If the NewCoin is unlisted, you can withdraw NewCoin from the exchange for free.

And it is quite easy to do.

ii. Taking the Exchange’s Money

The formula is:

- Deposit OldCoin to the exchange;

- Withdraw it;

- Check for any NewCoin you may have received, and split these UTXOs2 if they exist;

- Repeat. (Ie, take the OldCoin from step one and re-deposit it to the exchange).

You are now “fishing” for NewCoin.

Above: “Fishing”. Free image from pxhere.com.

iii. Why It Works

It works because, when the exchange sends you your OldCoin withdrawal in step [2], they may have created a replayable txn (unbeknownst to them). If they do, you will get an equivalent amount of NewCoin for free. However, when you send in the OldCoin deposit, you will always be sure to construct a non-replayable txn, and so the exchange will never get their “equivalent amount of NewCoin”.

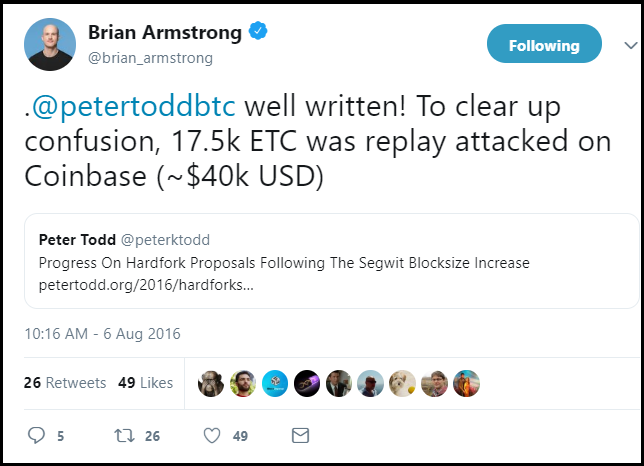

Above: Tweet from Brian Armstrong.

Many of the exchange’s customers will also be unaware of the second network (NewCoin). As these customers deposit OldCoin, they will unwittingly supply the exchange with fresh NewCoin. And so the fishing can continue! The fishing only stops permanently when the exchange becomes “NewCoin aware” – ie, when it takes measures to track the NewCoin and purposefully sequester it from the OldCoin.

If they are willing to become “NewCoin aware”, they may as well list the coin. At that point, listing the coin will cost them nothing; and the new offering will provide the exchange with a new revenue stream.

iv. It Can’t Be Stopped

But let us imagine that an exchange becomes “NewCoin aware”, but it still does NOT list NewCoin. Instead, the exchange takes all of the NewCoin that is sent to it, and keeps it for itself, in all circumstances. Let’s call it a “Sequestering Exchange”.

In this case:

- The Sequestering Exchange may be sued for Unjust Enrichment, as users are deposting money to the SE, and the SE’s balance sheet is increasing, and the SE knows that its balance sheet is increasing, and has all the tools in place to credit the user. And yet still consumers receive nothing for their NewCoin deposits.

- The Coinbase market price of OldCoin should drop below that of the OldCoin price at an exchange that handleds the situation differently, allowing price discovery and normal market activity to take place.

For example, a “NewCoin aware” exchange might not Sequester, but it might mandate that the two assets remained “joined”. In other words, this exchange does not credit you with “OldCoin” unless you deposit OldCoin and NewCoin in equal measure).

| NewCoin Aware | “Sequestering” | “Joined” (Mandates Both Coins) | Outcome |

|---|---|---|---|

| No | N/A | N/A | Users can steal from (ie, “fish” from) the Exchange. |

| Yes | No | No | Exchange must have listed NewCoin. |

| Yes | Yes | No | Exchange sued; price disparity created [against Joined exchanges]. |

| Yes | No | Yes | User inconvenience; Price disparty created [against Sequestering exchanges]. |

Buying 1 OldCoin on a Sequestering exchange will always get you exactly 1 OldCoin. But buying 1 OldCoin on a Joined exchange will always get you 1 OldCoin and 1 NewCoin.

As a result:

- With basic subtraction, we can derive “the market price” of NewCoin alone.

- “Indifferent users” (those who know nothing about NewCoin and don’t care), will “buy low and sell high” – they will tend to buy on Sequestered Exchanges, and sell on Joined Exchanges.

Since Joined Exchanges give crypto-sellers a better deal, “indifferent users” will flood Joined exchanges with fresh coins. These users think that they are getting free arbitrage money; but what they are actually doing is selling their NewCoin. They just do not realize it.

So the GARP coin is de facto listed, no matter what the exchange tries to do.

E. Has A Non-GARP Hard Fork Ever Succeeded?

i. Ethereum’s DAO Hardfork

In my view, only one prominent hard fork has truly succeeded: the July 2016 Ethereum Foundation hard fork, to reverse the effects of the DAO.

When I say “prominent” hard fork, I mean to exclude trivialities – such as bugfixes to very very early stage projects.

And by “truly succeeded” I mean that NewNet appears to have “replaced” OldNet in the apparent opinion of the network participants. Specific metrics for this include: market capitalization (an investor referendum), the daily transaction volumes (a user referendum), github commits (developer referendum), conferences and scholarly work (researcher referendum), and “who gets the old ticket symbol” (exchange / trader referendum).

The interesting thing about the ETH Hardfork is that it began with no replay protection at all, and with no contention. (So, it looked as though OldCoin would surrender, and there would be no network split at all). But when contention arose, unwanted txn replay began, ETH quickly implemented an “ETH splitter tool” in the new software. Since indifferent users would have to manually take advantage of this tool, the overall “ETH HF system” ended up approximating GARP.

So, the only serious HF to succeed, used GARP or something very very much like it.

ii. Bitcoin Cash

BCH, in contrast, was a prominent hard fork that has so far failed to succeed. It has not replaced BTC in terms of market cap, developer activity, awareness or usage (stress tests notwithstanding).

What BCH did is almost the opposite of GARP. Instead of activate RP gradually, it was activated all at once. Instead of cater to the indifferent users, it thrust them immediately to a side. Worst of all, instead of allow people to upgrade on their own time, the presentation timeline of BCH ruined people’s ability to figure out what BCH was and what it was all about. This timeline included a surprise unexpected launch on Aug 1, 2017, and then a Nov 2017 “re-branding” of BCH as “the” largeblock hardfork of Bitcoin Core. Unfortunately, the long period of uncertainty stimulated coordination anxiety (instead of reducing it). It is easy to believe that many “opportunists” (those who quickly cashed out their BCH for BTC between Aug and Nov 2017) were actually largeblock supporters who believed in the viability of SegWit2x. So the largeblock train may have left the station on Nov1 with many of its supporters left behind.

That is completely the opposite of what is desirable in a hard fork.

Above: Trapeze artists; from this slide deck.

F. Conclusion

When a network forks, most users will ask themselves “Which network are most other people on?”. This is basic network effect economics, and it prevents the two rival networks from competing on their merits.

GARP tries to make this question impossible to answer, for as long as possible, while still allowing speculators to easily choose a side as soon as they like.

Footnotes

-

Unfortunately, blockchains do not (yet) coordinate the departure of their users. So we cannot (yet) use a blockchain to solve the problem of “switching blockchains”. ↩

-

These NewCoins will end up “at” the same “address” as the OldCoin. So you will be able to export the private key (or whatever) from your OldWallet, and import it into your NewWallet. ↩