Bitcoin’s Decentralization increases as a full node becomes cheaper.

Agenda

- Break down “Decentralization”, and “Money”, to determine, from the ground up, when “Decentralization of Money” increases or decreases.

- Defend that measure against its major competitors.

- Evaluate the measure against scalability comments made by Satoshi.

- “How to (Safely) Increase Decentralization”

Defining Decentralized Money

The process of “money” is “knowing you’ve been paid”. A process has greater “decentralization” as it “occurs more locally”. Thus “decentralized money” is the local cost of knowing you’ve been paid: the cost of running a full node.

Let’s break the concepts down, before building them back up.

“Centralized” and “Decentralized” are words which describe the layout of the relationships between agents. Let us start with what these relationships are (in our “money” case) before we assess any of their other qualities (“decentralization”).

Money

Money is like a big record of who has done favors for whom, but a very abstract record which works without knowing the specific identity or favor. That’s how you can trade money with someone you’ve never met (or will never meet again): it makes private value-knowledge common.

That’s what it does. How can we make something do that? How can we build a “payment network”?

It seems there are two simple requirements: [1] to know when you’ve been paid (for the favor you gave), and [2] to be able to show your trading partner that they’ve been paid (for their favor to you).

The two requirements are mirrors: if “something” can do the first, for everyone, it can likewise do the second. There’s no reason to double-count it.

Money is “knowing you’ve been paid” (by someone, with finality).

Decentralization

Now lets see how a money-relationship varies in its centralization-quality.

Basics

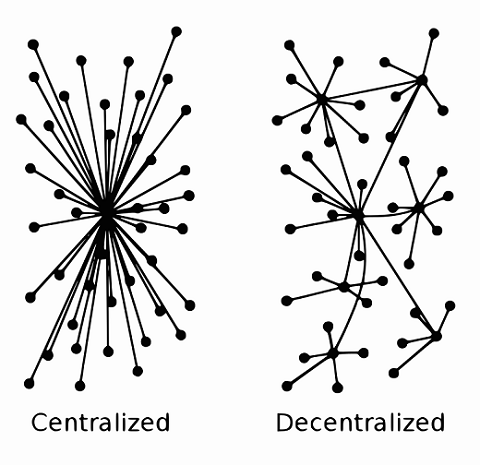

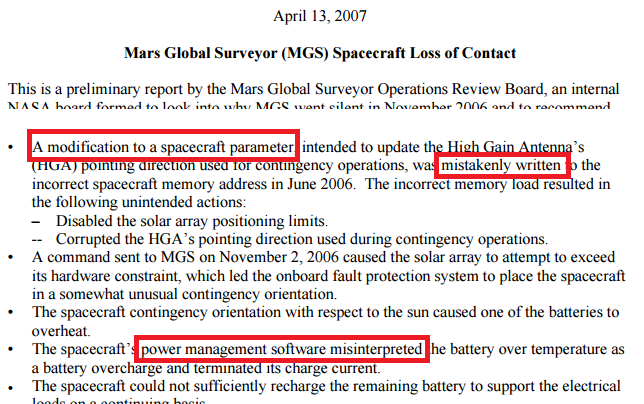

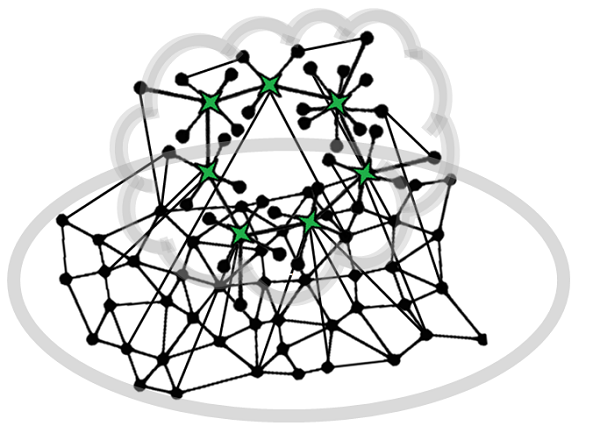

Some existing academic literature might help us with the general concept of “measuring decentralization”, but it’s nothing we couldn’t have figured out on our own (that “the process takes place closer to each agent”).

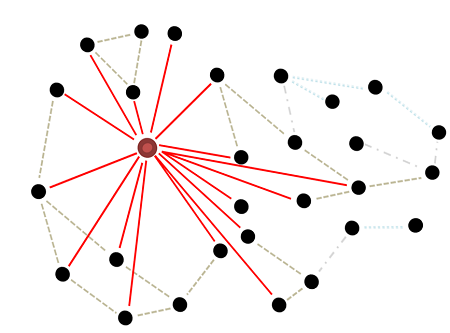

This figure spells it out for us:

The decentralized system is more local: the lines (pairwise-connections, or “relationships”) are shorter. It also involves less “interaction” (path-overlap) and hence, less “permission”: on the left all node-paths must share the single central node, but on the right it is possible for some pairs to ‘group up’ in ways that avoid the center node.

Now we must discuss Satoshi’s use of the word “decentralized”.

A “Peer to Peer” Electronic Cash System

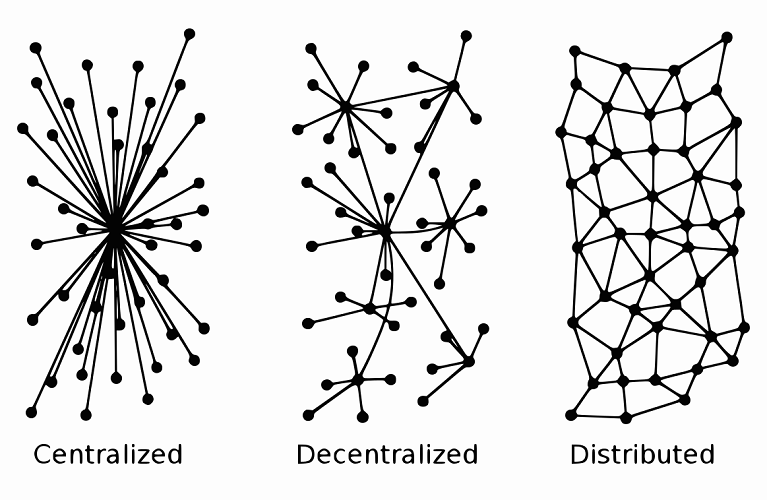

Satoshi clearly intended “the Bitcoin Network” NOT to be “more decentralized than usual”, but, instead to be 100% decentralized. In other words, the one on the right:

After all, the “Decentralized” process above (middle) still has a center, which is a superior authority (non-peer) to the surrounding subordinates.

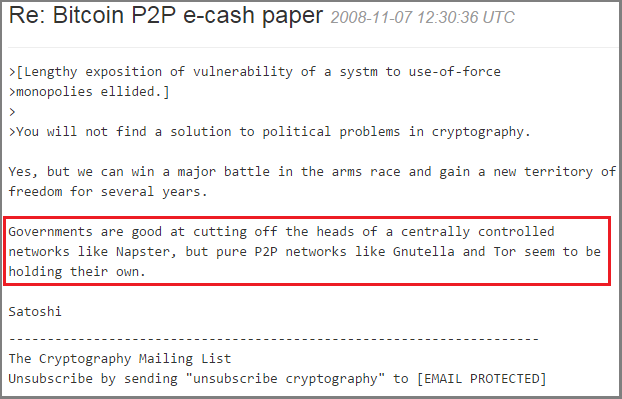

And, such a “having a center” contradicts this statement from Bitcoin’s Creator:

Notice the phrase “pure P2P”. Bitcoin’s whitepaper never uses the word “decentralized”, instead favoring the term “peer-to-peer” (which is very easy to measure: “Is every pair of nodes ‘two peers’?” and/or “Does any node have a privileged status?”).

The phrase “cutting of the head(s)” is a clue to the underlying principle: “Why is Bitcoin P2P?” (Might we achieve this goal another [non-P2P] way?)

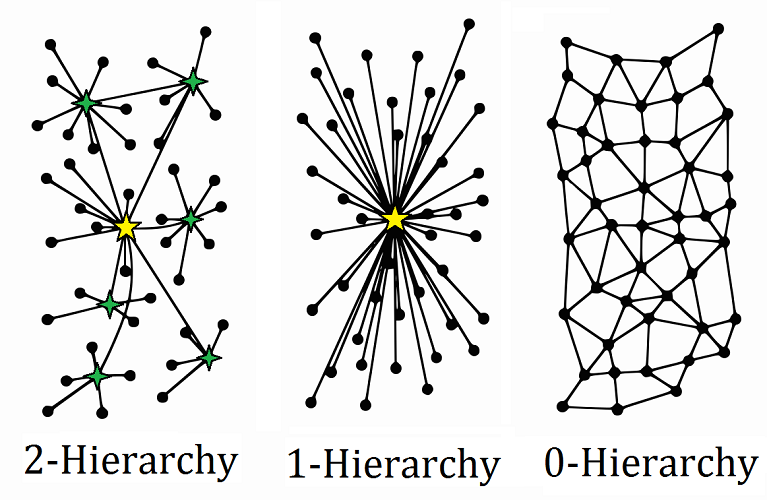

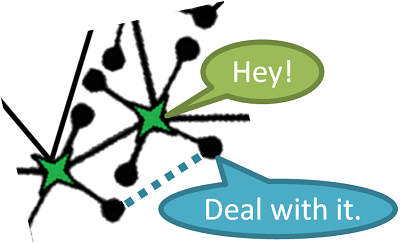

Clearly, the “Decentralized” image still has a “head” that can be “cut off”. In fact (worse than that), if I reorder/relabel the images, the “decentralized” option is the most-headed of all!

The colorful stars represent “privilege” in the network. A decapitateur could take out the Capitol Star in either the 2-H or 1-H, but his control over 2-H is even more fine-tuned. Instead of all-or-nothing, he can selectively disable the network for enemies only.

This “decapitation-control” brings me to my next point:

It is an Engineering Requirement that Bitcoin be “Above the Law”

Obviously, people prefer not to talk openly about breaking the law, but if we don’t acknowledge true things, our conclusions will be wrong.

What is the difference between the following columns:

| Computing | Legal |

|---|---|

| A user goes to a nearby terminal and logs in to a given mainframe. The user attempts to use his e-credits to purchase heroin at the e-store, but the mainframe rejects these instructions (as “not permitted”). With some effort, the user cleverly circumvents the programmed limitation. However, the administrators of the mainframe later use the mainframe’s logs to track this activity down. New limits are imposed and the offending user is banned, losing access to all of his digital resources. | A citizen wakes up within the borders of a given country. The citizen attempts to use his Bitcoin to purchase heroin at a nearby pharmacy, but under current law this is “not permitted”. After some effort, the user manages to break the law by transacting with a street dealer. However, the local police begin to carefully patrol the area to track this activity down. After studying the local black market, the drug offender is jailed, losing access to his freedoms completely. |

| A user goes to a nearby terminal and logs in to a given mainframe. He has been running UserBank, which lets him and his friends keep track of who still owes who money (for beer and whatnot). This user recently discovered cryptography and wants to take his banking software global. When the administrator learns of this, he decides he does not like it (for whatever reason), and sends the user a notice that it will not be allowed. Not wanting to do anything that might upset the administrator, the user takes UserBank back to pencil-and-paper. | A citizen wakes up within the borders of a given country. He and his immediate social network have been bartering favors (repair, electrical, painting, babysitting), which is cheaper and more fun than filling out tax forms. New, untrusted people want to participate, and they are willing to use an accounting ledger to keep track of who owes what. As the barter-network grows, the government finds out about it and audits these individuals for tax evasion, imprisoning the ledger-keeper for money laundering. Next year it’s back to “friends only”. |

| The system administrator can determine what commands are allowed on the computer network. | The legislators determine what actions are legal within the borders of their country. |

Only things that can break the law are truly P2P, ie truly 100% decentralized. Compliance with the law is the acknowledgment of a “privileged non-peer”. If the process is subordinate to the law, it is “owned” by the law exclusively, undermining the benevolent force of competition (for better or for worse).

You can spin it however you like (“the first software application to self-maintain its subordinate OSI layers”), but it is what it is: above the law.

Combining the Two: “Decentralized Payments”

Setup

Money is “knowing you’ve been paid”. When does “that knowing” occur more locally?

Experience vs. Persuasion

To learn anything, you can either [1] check for yourself, or [2] trust the judgment of someone else. Trusting someone else implies a loss of local-ness. It definitely implies that P2P is lost: you are a subordinate taking the information from an authority. To preserve P2P, you’ll have to check everything yourself: run a full node.

The requirement to run an entire full node may seem like a high bar, but the height is appropriate. With money, other people’s actions (counterfeiting) affect you. The only way for you to know you’ve been paid, is to make sure that every piece of data has followed every rule, and you can’t do that unless you have all of the data, and all of the rules, in front of you. That’s a full node.

It is also reasonable to require that this node start from scratch, for the very same reasons: to learn something, you either validate it yourself or trust an authority. Authorities are not “peers”.

“Don’t Make Me Call My Full Node”

Of course, one need not actually go through with the actual running of the node. That would imply that Some Guy in the remote African wilderness, far away from any internet connection, could declare “I refuse to run a full node” and somehow decrease the decentralization of “Bitcoin”. Only the cost of running the node matters, not the number of people who choose to pay that cost.

And, technically, the centralization measure is the cost of the option to create a new full node, because in strategy/anything-reasonable only Options matter. Of course, the cost of “creating a node at time=t” is roughly the same as the cost of “creating a node at time=(t-X) + running 1 node for X time”. However, this helpful detail does imply that some unconsumed electricity is “free decentralization” (people can avoid running the node, unless Something Bad is currently happening), and it does perfectly tie up the edge-case where the full node count drops to zero (and new full-node creation is infinitely expensive), because option valuation includes uncertainty surrounding future costs.

So my metric of centralization is the cost of the option to create a new full node.

Testing the Definition (Applications and Alternatives)

The definition mirrors our observations. It flags “suspicious services” (Ripple, checkpointers, …) as centralized, and is more fundamental than rival considerations (mining and development).

For this section, the cost of the option to create a full node will be referred to as the “cost of node-option” or “CONOP”.

Applications

Extreme Points

What if the CONOP were free (ie $0.00)? That would imply perfect decentralization (centralization of zero). Is that right?

I think so: anyone, anywhere, would be able to make sure that they had gotten paid, without trusting a third party, or doing any other work whatsoever. And this option would be available to every human on the planet, no matter how oppressed/disadvantaged (and the only way for a government to “cut off the head” of the network would be to kill every human being on the planet).

On the other hand, what if the CONOP were expensive, such that only one agent in the entire world could run a full node (say, the United State Government)? This agent would control the network completely: perfect centralization. If someone “cut off its head”, this network would disintegrate.

In fact, the logic works perfectly, in reverse, to explain existing monetary systems: the cost of creating “a full US Dollar node” is more than anyone could afford, by deliberate design. If, by magic, all of the USA’s banks / federal reserve / treasury buildings and equipment suddenly vanished, how many people would be able to replace them? Only one. Despite the fact that many, many people could, in principle, start a bank from their garage (and try to satisfy this unmet banking demand), we all know that they would be unable to do so. It would be illegal.

Ripple

A popular view is that the supposedly P2P Ripple is actually completely centralized. Does CONOP lead us to the same answer?

( Currently it is unambiguously centralized. And CONOP catches this: Ripple only allows one full node [theirs]. Adding a [second] node is infinitely expensive. )

But what of its eventual steady state?

Well, while anyone can become a Ripple “node”, not all nodes are equal “peers”. Extra-special nodes make the “default Unique Node List (UNL)”, which requires the approval of Ripple. The future “cost” of this approval is highly uncertain. Just as an option price converges to today’s spot price as volatility increases, you can’t guarantee you’ll be able to join the future Ripple club unless you’ve already joined today.

Actually, even that won’t work: the Ripple scheme allows you to be “thrown out” of the UNL club. In this way, Ripple doesn’t really have full nodes at all.

But lets run with it: To “know you’ve been paid”, you need to join the club, and stay in until your payment(s) go through. So the application of CONOP actually requires, that, to know you’ve been paid, you need to be “long a call option to join Ripple” + “long a put option that you’ll be thrown out before you can use Ripple”.

The second term (the put), acts as a kind of insurance that fully compensates you if you are kicked out of the club. However, because [1] “full compensation” is “them knowing they’ve been paid” (impossible to provide, by circular reasoning), and [2] because the likelihood of being kicked out is highly subjective (“volatile”), the cost of the option is infinite for everyone except the 1 person who controls the UNL: Ripple Labs. If RL were destroyed, the gatekeepers would then be “a coalition of 80% of the club members”.

Only they really “know” if anyone has been paid. Not you.

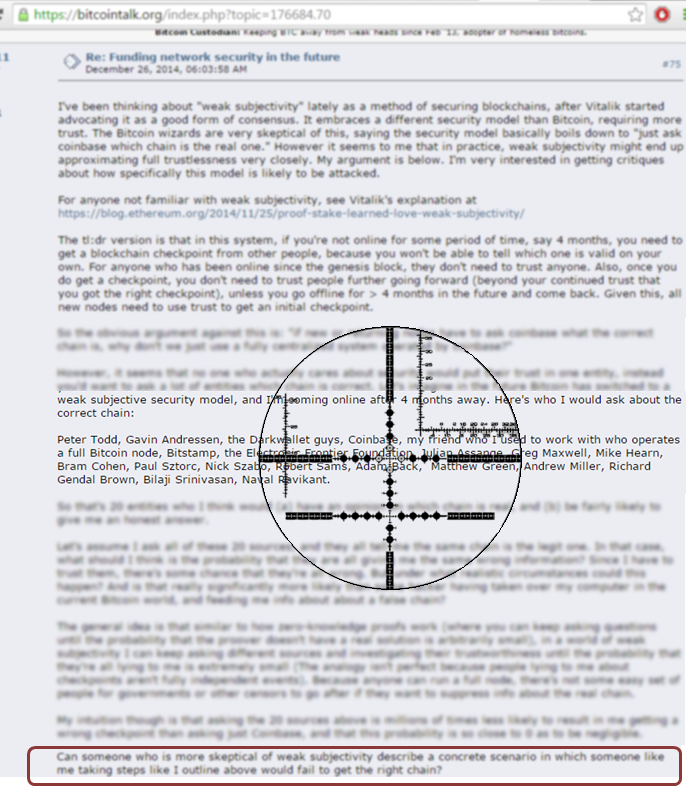

“Ask A Friend” / Weak Subjectivity

Summary

“Ask a Friend” is a scheme where one decides if a chain (“transaction history”) is valid by asking a friend, and taking their word for it. (Obviously the Friend has a superior non-peer status, so this is an outright rejection of “pure P2P”). If two friends disagree, (presumably) one asks a third friend, making it pseudo-democratic. This implies that democracy’s trademark effort-saving info-strategy will emerge: political parties. Specifically, the formation of alternating major/minor status groups (who “team up” to be realistic about winning), and fringe groups (who refuse to compromise on their principles, and always lose) resulting ultimately in a Status Game.

Non-CONOP Comments

A high-status individual with “name recognition” (such as Gavin Andresen), can completely overpower even a group of honest/well-informed friends. This is because name recognition is common, and allows for “free coordination”, whereas private or even mutual* knowledge do not allow for such coordination.

* There is a definition-mismatch in the video, Pinker’s “mutual” knowledge is wikipedia’s “common” knowledge.

CONOP

What’s the cost of “knowing you’ve been paid”? Well, with “ask a friend”, you cannot (by yourself) learn whether or not you have been paid. You are asking a friend! The cost is infinite unless you join the set of “those who are asked”.

So this scheme is essentially a version of Ripple’s UNL, but with no “default leader”. The paramount question “How do I join The Group?” is answered with “The Group decides if you can. We also decide if you can stay.”

If “joining the group” is cheap, this is fine. However, the “cost” of membership is public name-recognition, yet this is incompatible with anonymity, and hence incompatible with coercion-resistance. Only one agent, the sovereign government, can “afford” to maintain the monopoly on violence it takes to remain in this set (“can afford to run a full node”).

In contrast, Bitcoin’s proof of work is easily verifiable (“common” information, implying “free coordination”), and the Work would live on even if the miners who provided that work were killed. Reputation doesn’t work that way: someone needs [1] to be a reliable reporter of info, and [2] to be known as a reliable reporter of info…this is exactly the super-linearity that Bitcoin explicitly avoids!

Figure: the economics of degenerating (non-common) information (a zero-variable cost good): why settle for less than the best?

Checkpointers

This is perhaps the clearest victory for CONOP. Entirely by construction, only one person “decides” who has been paid and who hasn’t. Perfect centralization.

Now that the definition is viable, let’s see if it holds up to its competitors.

Alternative Definitions of Centralization (Have We Missed Anything?)

A Big List

Here’s a (well-meaning) list on this topic written by someone who isn’t me.

Let’s boil it down:

- Many members of the list (node, wallet, block explorer, payment processor, remittance service) are merely cosmetic layers on top of a Full Node. Certainly, they add convenience (and value) to Bitcoin, but the protocol itself isn’t even aware of them. Instead of repeat “Full Node” five times, we’ll just keep it once (although I will discuss ‘cost’ vs ‘other attributes’).

- Mining: while originally also a “plugin” of Bitcoin Core, mining has since specialized to a degree where the representative full-node-user is completely divorced from the mining process. So that’s a distinct #2.

- Some items (community, wealth) can’t themselves affect the software (or its use) at all. Ignore.

- Exchanges: a Bitcoin Full Node inherently supports “exchange” for everything (currency included), and could have a “LocalBitcoins Plugin”. Moreover the “professional exchanges” are half-fiat, and can be altered -in quantity and quality- by factors which are entirely non-technical (laws/subsidies). So they are simultaneously irrelevant and immutable.

- Software development: clearly a solid #3.

So I have to justify “cost” of a full node, and defend it against 2 challengers.

Counting Full Nodes Is Irrelevant

It’s popular to reference the quantity of full nodes (another attempt at measuring decentralization focuses obsessively on counting things up and taking their log_2(Quantity) ).

Is this measure actually useful? Or is quantity an effect following the underlying cause.

You Are Indifferent to Other People’s Nodes

I, personally, first heard it from Peter Todd: “The only full node that matters is yours.” This is the point I raised above: to know anything, you either [1] check for yourself or [2] take someone else’s word for it.

( Of course, [as I also mentioned], they are [slightly] related: if the node count falls to zero, you will be unable to start a node. )

After all, a single entity (of any type) can run and control many full nodes. The (centralized) Federal Reserve system likely has 100’s of redundant copies of its “knowledge” (payments data, research, web site, operating infrastructure, …). In parallel, nothing stops a Bitcoin user from spinning up 100,000 new nodes that only he controls (and then halving them). So what’s to be gained by counting them up? If you run a node (or can run one at any time), then it doesn’t matter if the full node count falls even to one! You’ll always know the status of your payments.

Cost is King

An explanation based on cost makes the most sense: if creating a full, up to date node is nearly free (takes 10-20 seconds on a smart phone), we see that this network will have the desired “headless” property, and be completely local (even if the average number of nodes in existence is some “low” number like 5). Conversely, if the a node is so expensive that only 10 or 20 people can afford to run one, it can be easily disabled (via the “close e-gold” routine, 20x in parallel), or coerced/harassed.

Don’t Worry About Mining

Mining “Feels” Important; Disregard the Feeling

Money already mesmerizes people. Mining goes even further: it takes the “generation” of ancient mysticism (making something valuable appear from “nothing”), and adds modern computing technology and elitist tech-expertise, a round measure of esoteric h4x0r jargon, and finishes it off with a dash of “f**k the man!”.

Small wonder, that mining draws the attention of the audience.

Even freedom-loving, tech-literate Edward Snowden remarked: “weaknesses…make [Bitcoin] vulnerable to people who are trying to own 50 percent of the network…” which implies (incorrectly) that the miners “own” the network.

The Final Gear in a Vast Machine

There is a rampant misconception that mining is somehow important to Bitcoin.

Firstly, the true function of mining is not to provide security to the network, but instead to slow the distribution of coins, such that interested parties would join Bitcoin instead of cloning it into a competing system. Mining will fulfill that function, in a fully-P2P way, regardless of who is-or-is-not mining.

When Satoshi/Bitcoin-Experts use the phrase “secure the network”, they are using a somewhat different version of the word “secure”. If I say that my bank is ‘secure’, what I usually mean is that “no one is going to steal my money”. But Miners already can’t steal anyone’s Bitcoin.

It goes straight down to the tech tools used in Bitcoin’s design. Bitcoin is a ledger, answering the question “Who owns what, when?”. The entire first half (“who owns what”, aka “most of the actual ‘bank’ part”) of that question is solved using asymmetric key cryptography, and even the second half (“when”) is mostly solved with very clever structuring of data (into blocks, headers, hash chain etc) and creative use of cryptographic hash functions. Neither of those things have anything to do with mining; 0%.

Mining was brought in at the last minute to solve the P2P problem: “If X makes a transaction, and Group A hears about it, but Group B doesn’t hear about it, (and A and B are equal peers,) how do they decide if it ‘happened’ or not?”. Most of the Bitcoin whitepaper focused on this yet-unsolved problem, because Satoshi was a good writer, who knew that it would waste the reader’s time to go over those much-more-important problems that were already 100% solved.

If Bitcoin were a bank, Mining would be the clock on the wall.

It’s the crypto that does all the heavy-lifting.

The 51% “Attack”

I’m sure you heard from your friend that, like, miners can “reverse” transactions or whatever.

No Motivation

Most transactions are totally foreign to the miner; the sender, receiver, even the amount, are more or less unknown. The miner has nothing to gain whatsoever by reversing them.

Admittedly, reversal might be a problem for transactions that the miner makes himself. He may buy something in a store, and later want to reverse this transaction so he doesn’t have to pay.

Or, an irate government might roll in with some tanks, take over the mining facilities, and reverse transactions (or “pause” the clock, by mining only empty blocks), purely to create mayhem.

That certainly wouldn’t be cheap: troops have to eat, and anyone in possession of mining hardware (even via theft) who fails to use it for ROI-maximization incurs an opportunity cost.

But say they did it anyway.

It’s not very effective…

Ok, if the attacker also owns Bitcoins, he can double-spend these Bitcoins.

Once.

Assuming he doesn’t “get caught”.

Where “caught” is defined as “people come to understand that this 6+ block reorg was specifically unrepresentative of the distributed consensus process”, and manually flag your chain as invalid. If this (highly likely) event happens, nothing will be reversed.

Not only is the user’s money safe, but the attacker’s money is at risk! It is relatively uncomplicated to have nodes (or the honest 49%) censor all further transactions “from” this address. This would result in the attacker not only failing, but also having his Bitcoin “blacklisted” and essentially destroyed (increasing the value of all other BTC).

Whereas “ask a friend” was centralized, this isn’t, because the conditions under which it would take place can be agreed upon in advance (even coded into the protocol) and don’t change. No new judgment is required, only the protocol rules (and these rules are, you guessed it, common information, and they can therefore support “free/leaderless coordination”).

Peer-to-Peer Blacklisting

Although “blacklisting” coins is overwhelmingly considered to be objectionable, in this case I think an exception might be made.

What’s different here? Typically, “blacklisting” would violate two core principles of Bitcoin: [1] “reproduce the qualities of money”, and [2] “remain peer-to-peer”. Blacklisting [1] implies that some Bitcoins are different than others, a direct contradiction to the monetary feature of Fungibility, and [2] allows a list-manager to achieve a “higher-than-Peer” status.

However, “51%-attack-blacklisting” actually excels on both counts. First, it actually maximizes [1] Bitcoin’s reproduction of money-qualities, because, in my view, this loss of fungibility is more than offset by a large gain in transaction finality (a much more important feature of money). Second, if the blacklist-conditions are publicly discussed and agreed-to in advance, there is no need for a “list-manager” to coordinate the blacklisting, and no one has a “higher-than-Peer” status.

So, the 51% “attack” requires a huge expenditure, to probably not achieve anything.

Mining isn’t Bitcoin

By no means should we ignore mining. However, try to keep in mind that a “centralized” mining network doesn’t really mean that Bitcoin is significantly centralized. Mining isn’t Bitcoin, it’s just something that Bitcoin does.

Now for a more complex topic:

Development: 100% Decentralized, Unless we Hard Fork

Soft and Hard Forks

A soft fork is a change to the Bitcoin protocol to make it more restrictive. A hard fork, in contrast, is a change to the Bitcoin protocol which makes it more permissive.

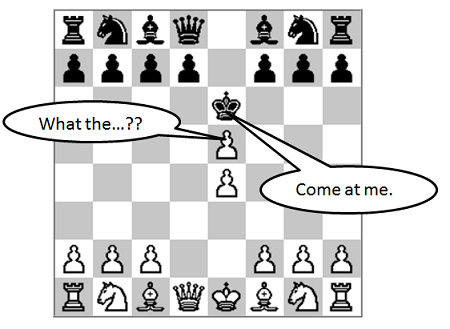

| Game | Soft | Hard | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Chess | Neither player can castle after move 10. | Any Queen can move three times in a row if her King is in check. | |

| American Football | A team can only score a field goal if they have not yet thrown an interception. | Any team up by 20 points or more can declare themselves the immediate victor. |

What is the effect of each fork-type?

Well, players are immune to soft forks. After all, there likely have been many chess games where neither player castled, and many football games where neither team ever attempted a field goal. Everyone can observe, or play in, soft-forked games with complete indifference (although they may become increasingly confused by a player’s seemingly bizarre moves).

Hard forks, of course, have a theoretically unlimited effect on the game. It depends on the details: in the football example, a team up by 20 will probably (not necessarily) win anyway. The chief motivation in football is to earn more points; it doesn’t change under the new rule. In contrast, the chess hard fork transforms the game substantially. Whereas, originally, checking your opponent’s king was highly desirable, now it is outright dangerous. Moreover, no one will sacrifice or risk the loss of their queen, and players might march the king out into the middle of the field, to trigger check (and the additional queen moves it grants).

Free to Choose

Un-upgraded software will, by definition, already be compatible with all future soft forks (and incompatible with all future hard forks).

For a given protocol, the user is free to choose among any soft-forks he wishes. The resulting competition is entirely centralization-proof: no authority can disable your version.

All versions are compatible, so, even if all the devs were kidnapped (and forced to write Evil Bitcoin Soft Fork), no one needs to upgrade. If you accidentally do upgrade, you can merely switch back. To “know you’ve been paid” you can run any version of the software you like, including the very first version!

Your version might be slower, uglier, etc, but it will let you “know if you’ve been paid”. It won’t allow YOU to be paid in a “new” (ie, “update-dependent”) way, and it won’t know if other people have been paid in a “new” way (because it necessarily doesn’t know why the coach chose to avoid a “post-interception field goal”: Was it to comply with some “new” rule, or just because he doesn’t want to?).

But all of your own money is protected by the “old rules”, no matter what fancy other rules other people play by.

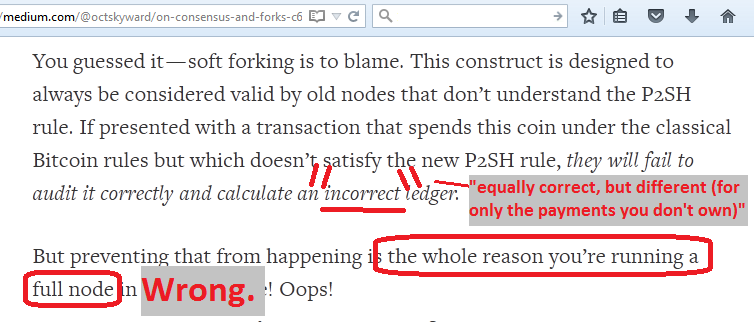

Figure: Mike Hearn’s bizarre obsession with money that doesn’t belong to him.

Hard Forks Threaten Bitcoin’s Accumulated Security

With soft forks, there are no surprises. Your money is protected by the “old rules”.

Because a system is only as secure as the adversarial environment it has historically survived, we can translate “..protected by the old rules” as “..safe” (for 6-year-old Bitcoin, anyway).

With hard forks, your money is subject to a new system. In principle, “a hard fork” could mean anything: stealing money, printing money, freezing the network permanently, it’s all on the table.

Therefore, the critical question is: “Are these new rules any good?”

Cost of Node-Option

To “know you’ve been paid” (ie “P2P money”) you need to know that the software won’t lose your money. After all, the definition of “paid” implies that the money now belongs to you and is controlled by you exclusively. Whether you lose your BTC to theft, or you lose them because the entire network collapsed, “you” have been “unpaid” (and you instead “know that you’ve not be paid”).

On top of that, if “the network” (users, merchants, service providers, …) switches, you have no choice but to switch. If you refuse to switch, and stay on the minority network, your money will be useless and you will be “unpaid”!

So the cost of “knowing you’ve been paid” (the cost of “the option to run a full Bitcoin node”), necessarily now includes maintenance items, which YOU must pay if YOU are to KNOW you’ve been paid: [1] the cost of “validating” any new set of rules and [2] the cost of preventing other people from being deceived into accepting unproven rules.

Because you can only know you’ll be paid if the network uses rules that allow you to spend your future income.

Node Option = Hardware Costs + Privacy Costs + Maintenance Costs

…it’s really getting expensive!

Hard Forks Destroy Decentralization

If one avoids hard forks, we don’t need to ask “Are these new rules any good?” at all, and so maintenance costs will be zero. Developers will never have any privilege, and there will be no centralization.

Unfortunately, of course, this limits our ability to improve the software!

Instead we might try to only propose hard forks where as little as possible has changed, so that “Are these new rules any good?” is likely to be easy to answer.

Then, with [1] enough experts involved, and [2] enough time for them all to voice their concerns, the user could eventually be as confident that “the rules are good” as the net confidence of the experts.

Unfortunately, our experts just aren’t smart enough. No one is.

Prediction in Complex Systems

We will probably never know “if the rules are good”, which means that maintaining decentralized access to one’s money will be impossible under a hard fork.

The Ideal Conditions (Aren’t Good Enough)

While it is claimed that NASA’s shuttle program achieves a 0 bug rate (per 500,000 lines of code), that is actually not true. Even getting as far as 1 per 440,000 apparently requires 260 full-time experts (Bitcoin has barely a handful) working under “threat of death”, in an execution environment where they control 100% of the hardware and software, and there is no adversarial activity whatsoever, and no user input of any kind.

Ask them about it! Here’s Appendix D (“Flight Software Complexity”) of their report on getting it right:

The very first sentences quote sociologist Charles Perrow: “…about the causes of failure in highly complex systems, concluding that they were virtually inevitable.” He continues: “…when seemingly unrelated parts of a larger system fail in some unforeseen combination, dependencies can become apparent that could not have been accounted for in the original design.”

Of course, a space shuttle is really complex, right? Instead, why don’t we take something that has been operating continuously, without any problems, for like 10 years. Then, we’ll take the elite NASA programming team and have them change just a single parameter.

It does not get any better than that.

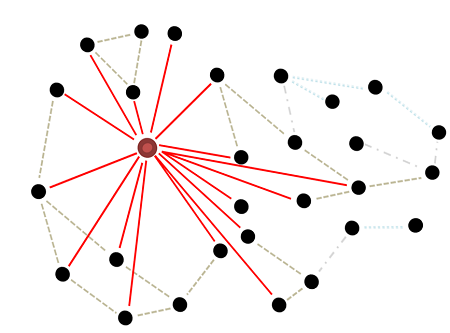

But, in the end, the Black Swan always gets his man:

Figure: this perfectly-healthy robot wound up entirely disabled after The Experts updated a single parameter.

Sound familiar?

Bitcoin is the Opposite of Ideal

Mankind will have perfected space travel long before we remotely understand software systems.

Just ask Greg Maxwell or Gavin Andresen. Or Mike Hearn.

Someone attempted to count up Bitcoin’s lines of code, and concluded that there were a little over 12,000. In order to reasonably predict that a hard fork is safe, someone must evaluate each change against every existing line of code.

But no, the fun only begins once you’ve done that. You now need to forecast, with perfect accuracy, the effect of the software’s new allowances on all real world attributes of the Bitcoin’s wider economic system, as well as all psycho-social responses (rational or otherwise), and all new opportunities (whether change-based or uncertainty-based) given to motivated adversaries.

No human being has the research capacity to actually do this.

So, you see, the average citizen is far more beholden to the developer who writes his software, than he is to the politician who writes his laws. Breaking the developer’s (more numerous) rules is literally impossible, and there’s no recourse (socially, politically, practically, …).

An Actual Example

Here’s a best-case scenario for a hard fork, because it is actually describable in advance:

- An 8 MB blocksize creates an incentive to selfish mine, such that miners must force all blocks to be 8 MB.

- The dramatic explosion in required bandwidth makes it impossible to run a full node anonymously.

- Because most presidents / current presidential candidates plan to use payments as a foreign policy negotiation tool, the “US Freedom America #1 Anti-Terrorist-Financing Emergency Powers / ‘Flags for Orphans’ Order” is “happened”.

- Anyone who runs a full node in the US is jailed, anyone who runs a full node in a non-US is flagged as a terrorist.

- Although some try to keep the node count afloat, the skills and resources required to do this are rare. These few are harassed, coerced, arrested, or outright assassinated.

- The Bitcoin project collapses.

Just think: with all the unknown unknowns, the true possibilities are unfathomably worse. One thing to point out is that a hard fork can be undone via soft fork. Since miners are the driving force behind soft forks (and since mining is capture-able), any hard fork which grants extra influence to miners would likely increase strategic complexity to a degree that could only be described as “unwise”.

But, protected by soft forks, you will never need to worry about all those things you didn’t understand until moments ago.

Contentious Hard Forks Obliterate Decentralization

I could go on (perhaps in a new post), but let’s wrap this up.

Grandma User does know that: “Bitcoin Core has been running for 6 years, it seems fine so far”.

Grandma User can not know that her money will be safe under the new rules of “Bitcoin Core II Duo”. She doesn’t have what it takes (150+ IQ points, technical inclination / CS PhD, a network of experts, and 100+ hours of free time), so, she must trust an authority. A hard fork elevates those who are Technical, Persuasive, or Endorsed, to “non-peer” status.

From there, the problem gets worse. Say x is the probability of hard-fork disaster, and f(x) is the probability that the “greatest expert” [1] catches the error, [2] is known (as an “error catcher”) to the audience (impossible to scale past 1-5 known experts) and [3] articulates his/her point clearly. As f is applied multiple times (as the info spreads to multiple people) the resulting f( f( f(x) ) ) will quickly degenerate to zero. Knowing this, individuals will minimize the number of f()’s and trust the Main Expert directly.

As with the very Federal Reserve System that Bitcoin aims to replace, these elite “non-peers” will [1] Team Up for greater collective clout per non-expert info-processed, [2] import credibility from top credential-ers, [3] entwine themselves with existing players, [4] formally entrench themselves to prevent the “wrong” people from making changes to Bitcoin.

In the extreme, an environment of frequent hard forks would eventually obviate the need for validation rules at all, and the people in charge would just be doing whatever they wanted.

The initial esoteric –technical and (subjectively) meritocratic– would collapse into a formal power structure. The minority who understood “original Bitcoin” will be powerless to prevent “new Bitcoin” from morphing slowly away from the principles that originally made it distinctive.

Conclusion: Remove the Contention

I’m not saying that we should never hard fork, only that doing so does tremendous damage to decentralization and is extraordinarily risky in general.

The decentralization of Hard-Forking can be increased as the “contention” decreases. I am aware of only one way to transform subjective judgments into objective information, as such a method must be itself P2P (“non-capture-able”, ie, allows anyone to express their [anonymous] judgment, without permission), incentive compatible, and produces a non-degradable signal (“common” knowledge supporting “free coordination”).

Decentralization increases if contentious forks are met with hostility: forked coins could immediately be sold, businesses who transact in them could be ostracized, individuals who support them should be discredited. A social norm of hostility would decrease the risk that a Bad Hard Fork will accidentally “unpay” everyone (ie, makes it cheaper for everyone to maintain their full node), but it would also make it harder to “upgrade” the software. It is a tradeoff, like anything else.

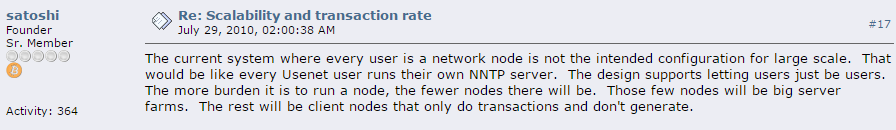

Bring on the Big Server Farms

Is an obsession with “cheap full nodes” consistent with Satoshi’s vision and statements?

Satoshi seemingly contradicts himself here:

In that he proposes something with two tiers (not “pure P2P”), such that, if everyone in the upper tier is destroyed, the network fails. I’m interpreting his analogy as something like:

Resolving the Contradiction

My interpretation is that Satoshi’s use of the word “node” is, in this case, overly liberal (ie, “incorrect”).

First, clearly these claims are true: [1] the intended configuration won’t scale, [2] it is impractical to have everyone validate everything, and [3] some users will lack the ability to run a full node, and that’s not a catastrophe (and able users are completely indifferent to it).

The Usenet analogy, furthermore, seems perfectly descriptive. However, Satoshi clearly intends all (or “enough”) of these “big server farms” to be safe, and these “NNTP servers” will be anything but.

Usenet isn’t Good Enough

I’m hardly an expert in this area (or, rather, this “era”).

But, what happened to Usenet? It became overloaded with spam, child pornography, and pirated software, and two non-peers (the government and ISPs) eventually pulled the plug (which is why 99% of the people reading this probably have no idea what the Usenet is). Once, the “Church” of Scientology used legal pressure to close down the (at the time) most popular anonymous remailer (a kind of Usenet “gateway”). Not exactly “headless”.

We don’t need to wonder “what would happen if Bitcoin were like Usenet”? It would overflow with spam and be killed by law enforcement.

Toying with Indifference

Of course, Usenet survives today as a paid service (and not a cheap one), but my feeling is that, if law enforcement knew or cared, they’d go back and finish the job. Today, Usenet is an enclave of the technical elite: it’s relatively complex to set up and use, its users are smart enough to not talk about it [sorry, guys…Satoshi brought it up…], and most regular people have no idea how the internet works at all (watch these people mis-describe a web browser as basically “a librarian they ask for help”, and these and this, and why not this) let alone Usenet. Usenet is, to borrow a phrase from Greg Maxwell, secured by “indifference”.

After all, you can’t care about something if you aren’t aware of it.

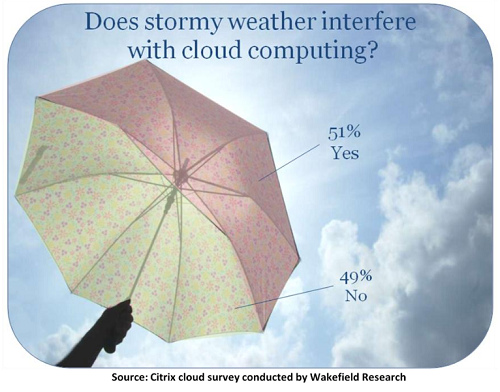

From a 100% real survey. Keep in mind that 50% of people will correctly answer a True-False question that they personally know nothing about.

Compare that to this:

“On day one in the Oval Office I would make two phone calls. The first one would be to my good friend Bibi Netanyahu, to assure him that we will stand with the State of Israel. The second will be to the Supreme Leader of Iran. He might not take my phone call, but he would get the message, and the message is this: Until you open every Nuclear and every Military facility to full, open, anytime, anywhere, for real, inspections, we are going to make it as difficult as possible for you to move money around the global financial system. I hope congress says no to [the Iran deal], but, realistically, even if they do, the money is flowing…we have to stop the money flow.” (emphasis added)

-Carly Fiorina, Widely-Regarded “Winner” of the Fox News 5 PM Debate for 2016 Presidential Candidate, beginning 39:50.

Conclusion (Usenet Analogy)

Usenet never prevented a US President from executing on their Iran “Anti-Nuke” Foreign Policy. Such a difference is too excessive (to sustain the analogy), and removes the (required) expectation of full-node-safety.

Which is interesting, because the NNTP analogy is almost perfect.

In fact, it more reminds me of…

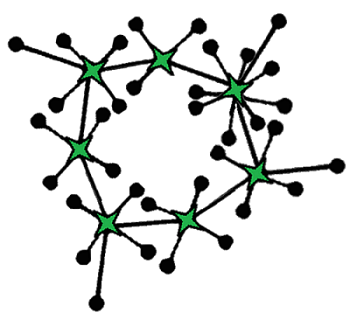

The Lightning Network

You see, it would really be something like this:

There’s cheap nodes, run by everyone, and no central authority. There is a two-class hierarchy.

An Authority on what?

The “upper class” in the Lightning Network is a little bit like a limited government: it exists to serve the public, and there are strict rules on what it can and can’t do.

It Can’t

The hubs can’t prevent you from becoming a hub yourself:

And they can’t prevent you from circumventing the hubs:

It Can

During the custodial period (about a week) The Hubs do get to determine if you will, or will not, be able to make a cheap transaction with the money you deposited with them. If they ban you from making any transactions (or, their computers get shut down by the government, or catch fire), your money is stuck there for the duration of the custodial period. However, it is only temporarily trapped: your money can’t be lost or stolen.

Basically, it’s a bank that can’t steal your money. Revolutionary!

Since anyone can become one, the resulting competition will result in maximal uptime and minimal fees for everyone.

Servers that compete on uptime? …just as is done today with…gasp…“big server farms”.

Reinterpretation

As Satoshi said, the current configuration is indeed not appropriate for large scale payments, that would indeed place an excessive burden on each user, “the design supports letting users just be users”, and a few “nodes” can be large server farms.

However, the Lightning Network configuration is much more rational, specialized, and efficient. To our point, it increases decentralization by making a full node cheaper: by allowing many transactions to take place off-chain, fewer happen on-chain, and fewer burden each full-node-user. This is true even if you refuse to use any off-chain transactions.

Increasing Decentralization

To improve Decentralization, make full nodes cheaper. One overlooked way to do this is with a “Tor supply curve” (which Bitcoin can provide)!

The Last Discontinuity

Given our conclusion, the easier it is to start up a new full node, the more decentralized Bitcoin will be. How can we make full nodes cheaper?

I’d ignore mundane expenses like hardware and power. Instead, recall that, if a full node cannot be run anonymously, “the network” (full node entry) is effectively controlled by law enforcement, a central entity. Therefore, my view is that the current largest “cost” (and current bottleneck to Bitcoin scalability) is therefore the threat of persecution.

It is a shame to have come so far, only have one tiny subjective abstraction interfere with my presentation of an actual number.

Intermediate-Good Bitcoin

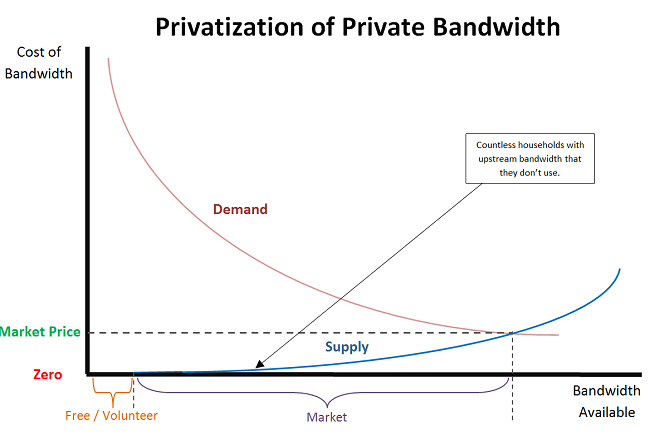

One way to address this bottleneck (and make decentralization easily measurable at the same time) would be to increase the supply of “Tor-Bandwidth” (or equivalent “internet anonymity”). However, Tor-Bandwidth currently has a big problem: the anonymity prevents anyone from paying for it. This means that it cannot be bought or sold, its price is fixed at zero, and we will only have what is volunteered.

Moreover, “available at no cost” also means “it can be attacked at no cost”. This is highly problematic, as the price cannot even react to the attack (“react to changes in scarcity”), and the lack of price prevents capital investments from efficiently increasing long-run supply. (After all, our internet service providers built the current internet to purposefully have limited consumer upstream bandwidth because that’s what the market told them we [could prove we] wanted).

Anyone looking to improve Bitcoin’s decentralization might look at integrating Bitcoin payment channels with Tor nodes (or metering bandwidth in VPNs, or in general). Keep in mind that more decentralization is not always better, but, as decentralization improves, we can be more comfortable “trading off” some for other things we’d like to have (ie, bigger blocks, and cheaper/more-numerous transactions).

Conclusion

To increase decentralization, focus on making a full node cheaper. “Decentralizers” include the Lightning Network, Tor, and metered bandwidth services.

I will be in Montreal to discuss this and related issues.

comments powered by Disqus