Human knowledge is not mystical – it exists physically in the brain. It approximates reality (including past or hypothetical realities), but can never match reality exactly – so all knowledge contains imperfections. Approximation is not only necessary, but also very helpful.

Part 1. “Fallibilism”

A. All Knowledge is Conjectural

During a Dec 2015 podcast, physicist David Deutsch remarked: “all knowledge is conjectural, and subject to improvement” (1:32:42).

His excellent book elaborates this point (page 9):

...To this day, most courses in the philosophy of knowledge

teach that knowledge is some form of /justifed, true belief,/

where 'justified' means designated as true [(or probable)] by

reference to some authoritative source or touchstone of know-

ledge. Thus 'how do we /know/?' is transformed into 'by what

authority do we claim?' That latter question is a chimera...

It converts the quest for truth into a quest for certainty (a

feeling) or for endorsement (a social status). This miscon-

ception is called **justificationism**.

The opposing position -- namely the recognition that

there are no authoritative sources of knowledge, nor any

reliable means of justifying ideas as being true or probable

-- is called **fallibilism**. To believers in the justified-

true-belief theory of knowledge, this recognition is the

occasion for despair or cynicism, because to them it means

that knowledge is unattainable. But to those of us for whom

creating knowledge means understanding better...fallibilism

is part of the very means by which this is achieved.

Throughout the book, he critiques various forms of “justificationism”, for example (my summaries):

- Argument from Authority: That knowledge “comes from” authorities (“elders”, “priests”), or authoritative books (eg, scripture, govt propaganda, classroom textbooks).

- Empiricism: That knowledge is “derived” from “experience”.

- Inductivism: The supposed methods used to conduct an empirical “derivation”.

- Positivism: That everything not ‘derived from observation’ should be eliminated from science.

- Zenoism*: That abstract attributes are interchangeable with physical ones, if they share the same name.

- Proof-ism**: That mathematical knowledge is more fundamental than (or, ‘a priori’ to) knowledge of the physical world (ie, physics).

- Computism***: The idea that computation exists prior to the physical world, and exists prior to (or ‘generates’) the laws of physics.

- Reductionism: That “lower level” explanations can always trump higher level explanations. (See “Hands vs Fingers” by Yudkowsky)

- Holism: That all explanations (of a given “level”) must always reference an abstraction that is one level higher.

- Relativism: The idea that truth and falsehood are objectively nonexistent, and statements can only be judged by cultural or arbitrary standards.

* My word, for the theory on page 182 “What Achilles can or cannot do is not deducible from mathematics. It depends only the what the relevant laws of physics say.”

** My word for the theory on page 188 “The whole motivation for seeking a perfectly secure foundation for mathematics was mistaken. It was a form of justificationism. …Mathematics [uses] proofs in the same way science [uses] experimental testing.” In contrast, Deutsch offers an alternative (earlier that page): “…the reliability of our knowledge of mathematics remains for ever subsidiary to that of our knowledge of physical reality. Every mathematical proof depends absolutely for its validity on our [valid understanding of] physical objects, like computers, or ink and paper, or brains.”

*** My word for the discussion on page 190.

B. Zenoism

Dr. Deutsch mentions ‘Zenoism’ (again, my word) only briefly in his book – a tremendous underemphasis. In my experience, if one mentions fallibilism in the real world, the audience will all start chanting Zenoist protests.

“2 + 2 = 4”

In particular, someone will almost certainly use a “2+2=4 argument” – they will claim that the “2+2=4” belief is unfalsifiable – ie, that no physical experience could refute “2+2=4”.

But there are many such experiences:

- Waking up in the body of a much older person; and being informed by your [older] wife/husband that you have been having memory issues lately; and seeing that everywhere you look, you see that “3” appears where you expected “4” and vice versa (each keyboard/wristwatch has a sequence of “1”, “2”, “4”, “3”, “5”, …).

- “2+2=3” ; hypnosis or brainwashing (ie)1, manipulation of brain simulation.

And also:

- Adding “2” and “2” in base three (instead of base ten), which would yield an answer of “11” …not “4”.

- On an arithmetic test, “2+2” is not really “equal” to “4” at all. See here.

- “Four!” on a golf course is not equal to 2+2.

- “A Priori” ; “you are, in effect, observing your own brain as evidence”.

- The equation “.999 repeating = 1” is just as true as “2+2=4” ( or is it? – bwahaha! ), but the former is, apparently, much less self-evident.

Zenoism illegally equivocates the physical and the abstract. So these refutations all involve severing the connection between the physical symbol of “2” (ie, right half-heart connected to a horizontal line) that our carbon-based eyes and neurons detect, and the the abstract concept of having QQ of Q. See the ‘languages as theories’ section soon below.

While there are “objective truths” about abstractions (probably), we can never access these directly. We only have access to our knowledge about abstractions.

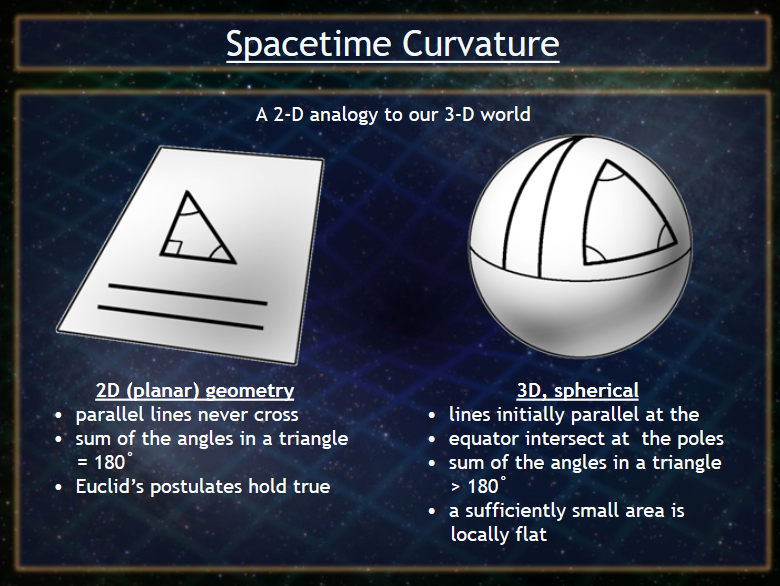

Geometry

Deutsch gives us a second Zenoism example, via triangles (page 183):

In the space near the Earth, the angles of a large triangle

can add up to as much as 180.0000,002 degrees, a variation

from Euclid's geometry which, for instance, satellite navi-

gation systems nowadays have to take into account. In other

situations -- such as near black holes -- the differences

between Euclidean and Einsteinian geometry are so profound

that they can no longer be described in terms of

'deviations' of one from the other.

See also:

Abstract triangles (such as Euclidean triangles) do not need to have anything in common with physical triangles (those that we could encounter while walking down the street; or those that we could construct, using string or lasers or plywood, etc). Even though they are both “three points separated by perfectly straight lines”.

This example shows us the uselessness of ‘unfalsifiable theories’. For a given unfalsifiable theory, our reality looks a certain way if the theory is true, and it looks exactly the same way if the theory is false. So each and every unfalsifiable theory is always 100% irrelevant to any real-world dispute about anything.

See also:

C. Languages as Theories

i. Mapping Symbols to Meanings

Dr. Deutsch also casually drops the sentence: “Languages are theories.” (in “The Fabric of Reality”, page 153).

It is short but very meaningful. It explains what languages (and all labels, and all symbols) really are: guesses about how “labels” and “reality” line up against one another.

ii. Social Truths

This is a stark contrast to the “magic labels” theory of Zenoism. If Zenoism were true, one would be able to force a broken refrigerator to become cold, by writing “cold” on it. Hence why Zenoism is false.

When labels are used for coordination (“in Australia, drive on left”), they may have some objective effect: subjective truths can become objective truths. But this does not change the fact that the labels are objectively connected to physical truths. Quite the contrary – they help to establish this very connection!

See also:

- The social world is not entirely objective.

- Humans are “influenced by the rhetoric, eloquence, difficulty, drama, and repetition of arguments, not just their logic”.

When words represent ideas, the theory is that the labels match reality – as with all knowledge, it is that the map matches the territory. You may find, at any time, that the connection that you thought was there, actually isn’t. This applies not just to words, but to all representations: numeric digits, graphs, figures, holographic displays, computer simulations, etc.

See also:

iii. Choice of Language

Finally, languages themselves are also theories that a particular language is objectively “better” than rival languages.

By “better”, I mean “more effective at its job” – in other words: better at standardizing “word <–> meaning relationships”.

In general, consistent syntax makes a language better. It’s easier to learn, easier to speak, and –most crucial of all– more easily succeeds at its purpose, which is to create sentences for which there is maximum overlap between the speaker’s meaning and the audience’s interpretation. But there are other criteria as well. The language must be expressive (it must be able to express a wide range of meanings), and yet it also must be tractable (it must convey its meanings quickly – unlike in Tolkien’s fictional Ent-language).

This is easiest to see with the evolution of our numeric systems. As we counted to higher numbers, we upgraded our language. We began by scratching lines; then added “tally” clusters; then proceeded to Roman Numerals; and finally to Arabic Numerals. When counting from 1-3, those four numeric systems are basically equivalent to each other (Arabic ‘twos’ and ‘threes’ are, if you didn’t know, just horizontal tallies written in “cursive”). But when counting in the 10-500 range, it becomes reasonable to abandon scratched lines, and instead insist on making use of the tally’s system of grouping-by-fives (or hundreds). Then, when comparing quantities in the 100-9999 range, it becomes useful to represent larger quantities with their own symbols (as the Roman system does). Finally, with Arabic numerals, it was noticed that “places” could fulfill the role of symbols (the role of representing large quantities), without ever needing any new symbols. The total number of symbols was capped at ten –ten fingers, ten symbols– the resulting system can represent any quantity.

When discussing spoken languages, the case is rather abstract and harder to make. But here is some reading:

- Pinker on the evolving precision of English, cultural evolution trumping overintellecutalization, to automatically and effortlessly improve the language despite obstruction from the villanous “mavens”.

- Lesswrong: “Your brain doesn’t treat words as logical definitions with no empirical consequences, and so neither should you.”

- Intro to Chomsky’s Universal Grammar

Applications:

- Gauss on “Imaginary” Numbers (emphasis: 2:06)

- Comparison of software ‘languages’ (“Rosetta Code”)

Homework Problem:

Continue to Part 2.

Footnotes

-

In the post-title scene, the Parasites try to convince Rick that he has written a six “for no reason”; and even that there is no difference between six and ten. Rick is momentarily flummoxed, but does manage to escape, saying (correctly) “…but I don’t get why I would do that”. ↩