Part 3. Knowledge As a Molecule

A. “Definitions” Part I

I will be introducing some definitions.

Here are the first few:

- Interaction (n.) / Entanglement : When one thing affects another thing, and vice-versa. If one thing changes, so will all other interacting elements. For example: you wave to a friend and he sees you; or the floor bends slightly to support your weight (and prevent you from falling toward the center of the Earth).

- You: The person reading this document right now.

- Reality / “The Territory” : All of the “stuff” that is actually “out there” (out in four-dimensional spacetime) for you to interact with.

- Co-vary (v.): When “a change in one thing” entails “a change in a second thing”. For example, “height” and “weight” co-vary (see below). The connection can vary in magnitude – “height (cm)” co-varies slightly with “weight (kg)”, but it co-varies absolutely with “height (meters)”. In the latter case, they are the same thing, and so their statistical correlation is +1.0, and the “R2” (shared variance) is 100%.

Above: “Height” co-varies with “Weight”, from this course. They are similar in this sample, both empirically (as we see above), but also rationally, because both measurements themselves co-vary with “the number of cells in the human body”.

- Representation (n.): A simpler thing that nonetheless efficiently resembles a more complicated thing (see “Compression”, next section).

- Information / “The Map”: A representation of Reality. Variations and interpretations that are stored on some medium (eg: a brain, or stone tablet, or hard drive).

- Truth: The objective connection between variations on the map and variations in the actual territory; a connection between information and reality.

- Error: The opposite of truth; the lack of connection between “stuff in The Map” and “stuff in The Territory”.

- Knowledge: The durability of the map – especially, its faithfulness, complexity, and efficiency. Eg, someone with a wrong map will get rid of it, someone with a more detailed map is “more knowledgeable”, but sometimes a map is too detailed to read easily.

- Explanation: Knowledge about [1] who is ignorant of something, [2] what, exactly, those people have failed to understand, and [3] what experiences could make these people change their minds.

B. Explanation

Explanations are interesting, because they contain many kinds of knowledge: [1] the speaker’s knowledge, [2] who the audience is, [3] what the speaker believes that the audience doesn’t know. For example, a parent might explain to a child how to take out the trash, oblivious to the fact that the child already knows how to do this. But it would still be an explanation of how to take out the trash.

Some things are very nearly self-explanatory, like video games. The first instruction is typically to “Press Start”, which is usually a button labeled in the very center of the controller. From then on, new instructions are slowly given out to the player, when needed. Typically the players subsist on ‘feedback’ alone, which they tend to find quite enjoyable.

Above: “Press Start” screen, and a dialog box about opening doors. From YouTube and from this walkthrough.

See also:

- Richard Feynman on “Why” Questions (and explanations, finite vs infinite regress)

- Nicky Case’s “Explanation” Videogames

Other things are utterly non-explanatory, such as the fabled Library of Babel. As I will now explain, they are “variation” completely devoid of “interpretation”.

C. Information = Variation and Interpretation

It is impossible to “have” any information, without “storing” the information (or, “measuring” the information – see Section 5). And storing/measuring information requires two things: variation and interpretation.

For example:

- Using black ink to draw alphabet characters on a white page – this is variation in color, and interpretation as Written English.

- Using raised dots on a surface – this is variation in texture, and interpretation as Braille.

- Encoding the words as sounds in a tape recording – this is variation in air pressure (sound waves), and interpretation as Spoken English.

The “interpretation” aspect is fundamental – in fact, “interpretation” is more fundamental than “variation”.

First, as I mentioned already, someone could truthfully respond to a written “ 4+4=9 ? “ question by speaking aloud the word “nine”, because an English “nine” sounds exactly like a German “nein”, and “nein” is the German word for “no”. Especially if they know that you can speak German. So the variations in sound are trumped by your interpretations of those sounds.

Second, notice that a “three” [as a piece of information about quantity] is still a “three”, whether it is spoken aloud or written down. (What Deutsch calls ‘substrate-independence’.) But you can’t listen to a written three, or glimpse a spoken three. So again, interpretation trumps variation.

Third, notice that tremendous information can be conveyed, even if there actually are no “variations”. For example, a mother might tell her child, “I’ll pick you up at 6, text me if you want to be picked up later.” Then, the mother would be receiving information throughout the day, even if the child sends no texts. At 6 PM she interprets the silence meaningfully – that the class project (or movie or whatever) has been finished by 6 PM.

So, all information is interpretation. Optionally, it is also variation.

D. Non-Contradiction and Interconnectedness

Knowledge is “interconnected”; no two pieces of knowledge, no matter how superficially separate, are ever allowed to contradict.

One implication of interconnectedness is that knowledge of anything is, partially, knowledge of everything. As I will explain in Part 5, one small instance of ignorance can imply total error about everything.

Secondly, since every idea has a “shadow-idea” which contradicts it (eg “the sky is blue” is a shadow-idea of “the sky is NOT blue”), it is impossible to be generally “skeptical” or generally “open-minded”. One must be specifically skeptical (ie, skeptical “that the sky is green”) or specifically open-minded.

E. “Physical Reality” and “Physical Knowledge [About Reality]”

i. Both Exist

Physical reality exists, and “knowledge” also exists. Knowledge is not only IN the physical world, but it IS itself a physical manifestation of some kind.

ii. Physical Objects

For example, it may be a printed book, or electronic computer code on a hard drive, or else it may be a program in RAM; it may be a program encoded in the wiring of our brains (brains are, after all, physical objects) – they are made out of fat, and potassium-pumps and electricity; and they even wrinkle [change shape] over time as you obtain more knowledge).

iii. The Physics of Learning

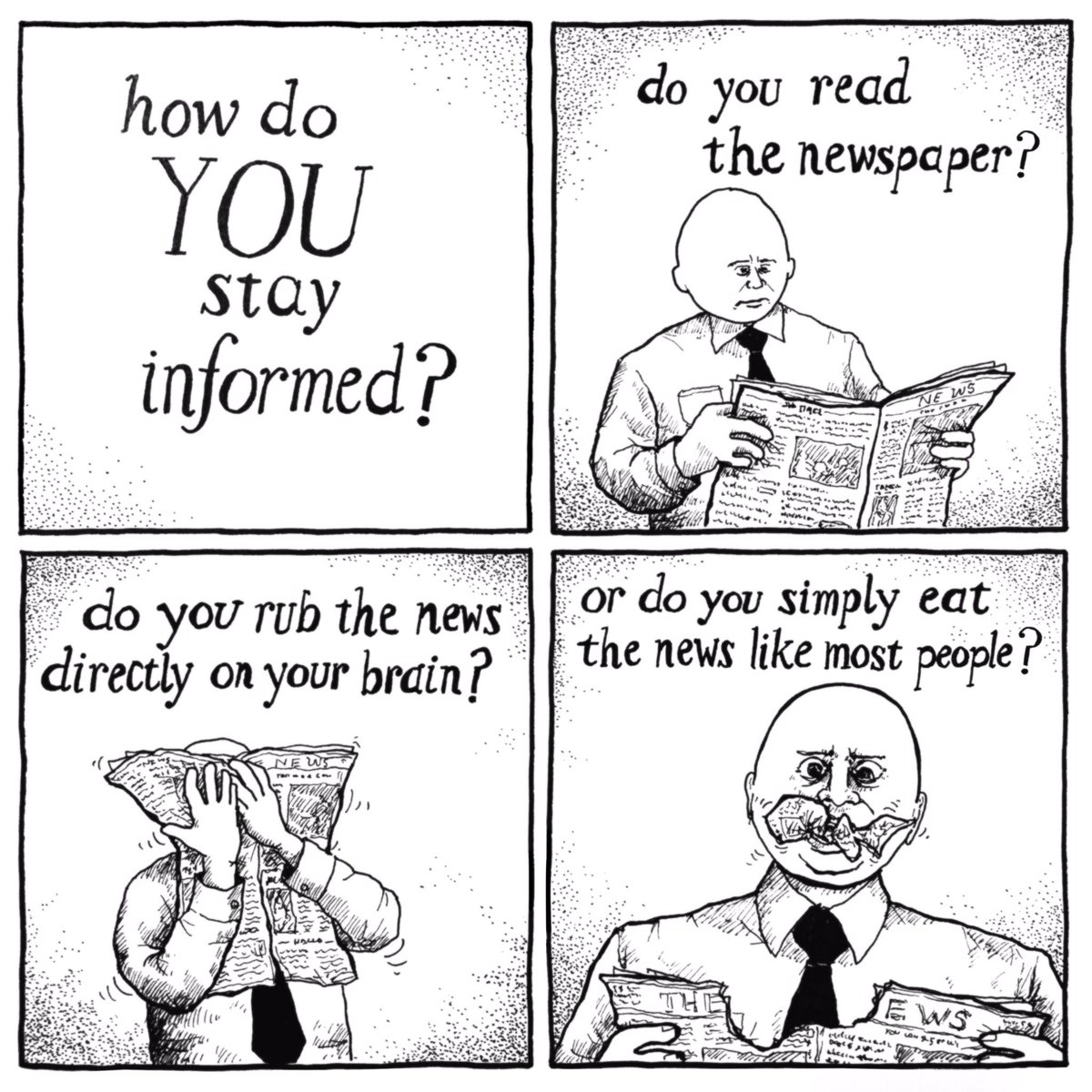

How might a physical brain become a more accurate Map of Reality? It would have to undergo a physical change.

Thus, all “learning” is also an act of “physical brain-transformation”. And therefore, it is inextricably entangled with the functions of our senses, and the neuronal wiring governing our perceptions (both of which are imperfect, of course).

Above: Newspaper-Brain entanglement. From jakelikesonions.

F. The Ad Hominem Fallacy

Consider a specific virus, with a fixed, given genetic code and a fixed molecular structure. It will either be adapted to its environment (in which case it will replicate itself quickly – more quickly than the environment destroys the replicators) or else it will not be.

The origin of the virus is irrelevant to these questions. It doesn’t matter if the virus was created in a laboratory; or if it slowly evolved in the wild by natural selection. As long as the genetic code is what it is, the molecular structure will be what it is, and so it is the same virus. Nor would it matter if the virus were formed through some kind of pseudo-miracle or “unlikely” chance event – for example, by lightning striking a vat of organic chemicals.

This irrelevance-of-origin applies to all life, all viruses, all crystals, all jokes, all memes, all computer viruses, etc. Their origin is unimportant. Of course, it might be historically interesting – it would be interesting to know, if it were the case that aliens visited Earth to provide us with radio technology, or to send out the first chain letters. But it would be irrelevant to the more-important questions of “Is radio technology a good idea?” or “Will these chain letters spread?”.

This irrelevance-of-origin also applies to things like books, or computer programs. It does not matter if a computer program is written by a single human, or developed in a large collaboration with many people, or else if it happened to write itself through some kind of outrageously auspicious disk corruption. In each of the three cases, if every line of code is identical, then the program is the same. Again, the creation-process may be interesting to some group of specialists (software developers, or software historians). But if every line of code is the same, it is the same software. And it either works for something, or it does not.

And it is the same with knowledge. Knowledge is either correct, or it is not. Its source is irrelevant. Attempts to locate a “source” of knowledge, are misguided. That goal makes absolutely no sense, which is probably why it has never helped anyone (and in fact reliably makes everything worse).

Part 4 is about abstraction and compression.

comments powered by Disqus