So-called “alternatives” to Proof-of-Work “waste” just as much “work”.

Intro: Wasted Resources

I previously wrote a post on proof of work (PoW) and mining. The first half generated great interest but (apparently) failed to be universally persuasive. For example, CCRG (Ethereum’s multi-million dollar funded “research” organization) consists almost entirely of academics theorizing about proof of stake (PoS).

So here I will expand on that first half, in the hope that less “work” by people with legitimate potential is “wasted” on these defunct ideas (and fewer journalists / empty-suit-“investors” are distracted from Bitcoin’s value proposition as the internet money).

Agenda

- Reintroduce the core theoretical concept (marginal revenue equaling marginal cost).

- Generalize it to every human activity, by explaining economic rent.

- Describe how >0 rent is incompatible with peer to peer money.

- Focus on some specific examples (Tendermint, Delegated Proof-of-Stake), while assuming that they follow Bitcoin’s issuance schedule.

- Generalize the argument to all issuance-schedules.

(Reprise) For Auction: 100 US Dollars, Payable in Anything

“Sold! For 100 US Dollars, to the miner in the Peercoin shirt.”

I previously argued that:

A: Releasing 50 new Bitcoins per block.

…was equivalent to:

B: Auctioning off 50 Bitcoins to the highest bidder.

…by the necessarily-true economic identity that production will always continue until marginal cost equals marginal revenue (MC=MR). After all, each hash has a cost, and each hash also marginally increases one’s likelihood of winning the 50 BTC. If any behavior (not just hashing) could increase one’s likelihood of winning the 50 Bitcoins, that behavior would be performed until the total behavioral-effort expended by society approached the total value of the 50 Bitcoins.

When applied to naive proof of stake (PoS), this principle implied the attack-phenomenon known as “stake grinding”, a version of PoW (“attempting multiple-block chain-histories until you found a history which granted you the coins”) that was markedly less-cumulative. Because the cumulative work wasn’t measured (as it is with Bitcoin’s “difficulty”), it wouldn’t be readily obvious that “total work” = “total expected value of the blockreward”.

In PoW there was sometimes disagreement over which NYTimes issue (of 1000’s) we should run tomorrow, in PoS there was disagreement on which stack of ~60,000 issues (of 1000’s) was really the NYTimes.

The discarded blockchain-histories (“NYT stacks”) weren’t presented, so you didn’t see them, but their creation took “work”. Over time, increasingly desperate developers pushed the work where it was harder and harder to see: all proposed PoW-alternatives could be relabeled “obscured proof of work”.

As we’ll see, changing the obfuscation-level (“complexity”) of a PoW algo will not alter this “bridge” connecting ‘world-work’ and ‘blockchain-influence’. Ultimately, each individual “miner” (or whatever) will always: [1] calculate their expected benefit, [2] subtract their costs, and [3] “work” to fight over the difference.

The “expected benefit” is the only alterable parameter of this system (not the “expected costs”, which chase it).

“Rent” always forces production costs (MC) to always equal sale prices (MR)

This “marginal cost” = “marginal revenue” concept actually applies to every transaction in the entire world, including all future blockchain tech.

Measuring Cost

A reasonable person might immediately protest that, in practice, MC=MR is never the case (for example: “I know they overcharge me for beer at the convenience store near my house”, “I own a small business and we mark everything up at least 3%, its how we keep the lights on and pay my family’s salary and I get profits on top of that…although I never know how large those profits will be, of course.”)

MC = MR is always true because of the way economists measure costs: the correct way. Specifically, through the contrived introduction of ‘rent’. The equation could be elaborated to: MC_rent + MC_nonrent = MR.

Since this probably sounds like cheating (to the econ-illiterate), I will first discuss rents in general, before arguing that, for P2P money, they should always equal zero (as opposed to something centralized where the central-bank/checkpointer can control/own the system and force people to pay nonzero rents).

What Rent Is, Why It Appears

As Described in Econ Textbooks

Imagine that a seller has a patent on something (only he can sell it). The seller can guess its benefit to his customers, and charge them “estimated benefit - epsilon”. If this fully-gouged selling price (MR) is more than what it cost him to make (MC), the difference is interpreted as “rent”. This amount (MR-MC) determines what the price would be of “renting” the patent (to someone) for the duration of these hypothetical sales. Although the seller doesn’t have to rent the patent from himself, by not renting it to someone else he bears an opportunity cost. Thus our new MC, including the op-cost of renting the patent, is now perfectly equal to MR.

It may seem contrived, but it’s the only logical way to measure costs. Imagine you spent $10 million on research, and in the process discovered some drug, which you can manufacture for $0.10 but sell for +$200.00. Does the drug really only “cost” $0.10? Why should “the cost” be measured differently for you, vs. someone else who has to pay patent-royalties, or duplicate your research?

Cough Medicine

Let me try to push the concept to its extreme.

When I have a cough, the marginal “revenue” (the benefit) to me of a single dose of cough medicine is extraordinarily high…I might pay $50 to make it through a single night. Yet I am fortunate: my cost for a whole week’s worth of medicine barely exceeds $5. Seemingly, MR > MC ?

Yet many rents are at play, and this time I (the buyer) own them, instead of the seller. My awareness of my own sickness is private (belongs only to me). I may also be aware of neighboring stores or competing products (whether or not I actually am “aware of those stores” is private, and known only to me). If all stores had a practical way of understanding my urgent need, and a way of blocking other people from purchasing the medicine on my behalf, and a way of blocking other stores from negotiating with me, etc., the store might try to price discriminate against me (and thus keep all the rents for itself). My ability to counter the store’s efforts (by stocking up on medicine while healthy, having someone else purchase on my behalf, or shopping at a rival store) are options that belong only to me. If the store knew that I would pay $200 for 72 hours worth of their medicine, they’d charge me that, but only I know this, and when I rent that info from myself I don’t have to pay anything.

While it may seem that MR > MC, what is actually happening is that I am buying one unit of “medicine”, and combining it with one unit of “sickness” expertise, to produce a new good “cough cure”. I can only make this good when I’m sick (the medicine has no beneficial effect on me when I’m healthy), no one can wait until I am sick and then prevent me from making the good, I already know that the medicine will cure my sickness, etc. So it is MC = Medicine + Sickness_rent = MR.

Rents are Private

MC = MR applies only to the agents involved in the decision at hand. It therefore ignores externalities (which is the entire reason that externalities can be problematic).

Rents Self-Destruct Over Time

While, today, you might be forced to “rent” something from someone else, over time you’ll be looking for alternatives (your inability to “shop around” today is costly to you…you must “rent” the knowledge of “Where’s the best deal?” because you do not yet own it). In fact, if you are an entrepreneur, you’ll do the reverse: look at these rents to see if you can provide what-people-want, at a discount. In this way, the economy allocates scarce entrepreneurial ability, and motivates the allocation of scarce capital to where it is most needed.

And, finally…

“Rent” Implies “Exclusion”, Which Contradicts P2P

If all peers are equal, how can some be forced to assume (and endure) a subordinate position?

Rent only occurs when a seller owns something that rivals can’t own, which is why the rivals need to “rent” it from the seller. Yet, the concepts of “exclusion” and “peer to peer”, are fundamentally irreconcilable.

The problem is not limited to the steady-state operation of the protocol, it extends to all areas, including the initial setup of the protocol. A fully P2P protocol will have a P2P operation and a P2P genesis. But, a protocol granting significant ongoing rents would beg the question: who are the privileged people we are renting from? Why them and not someone else? Why do we need to rent from someone at all?

The only entity on coinmarketcap capable of extracting rent is Ripple, for the exactly same reason that it is NOT P2P (it has a privileged, inimitable “peer”, and inimitable banking relationships).

I hope that wasn’t too painful. Now that you know what to look for, let’s get back to our original topic.

Everything Is Proof of Work

With no rents, and a “25 BTC / 10 minute” schedule, everything will waste 25 BTC, every 10 minutes.

For simplicity, this section assumes that all P2P systems release new coins at the same schedule (ie, at a rate of 50 units per 10 minutes, a rate which itself halves every 4 years). The following section will describe how changes to the schedule are irrelevant.

Is a “Work-Independent” protocol possible?

If any cryptosystem is to periodically release coins, without immediately creating an incentive to “waste” an amount equal to the value of those coins, the cryptosystem is going to have to release the coins in a manner which is totally independent of all possible human activities. The coins will have to be rewarded on a completely effort-blind basis. The coin-reward must have a Spearman correlation of zero with everything that mankind could influence.

This isn’t going to be achievable. The very decision to use the software is human-influence-able, and the protocol is blind to non-users. It follows that effort-blind coin-distribution is completely impossible…making so-called “waste” completely inevitable.

Distorting Time and Ownership (Won’t Matter)

Consider a design which [1] randomly determines who gets the 50 BTC reward in advance, [2] freezes that determination, and -only much later- [3] actually pays the 50 BTC out. By the time the MR was coming around, there would be nothing anyone could do to “work” toward getting it, right?

Wrong.

Timing

While it is true that, by the time [3] rolls around, it would be too late to “work” toward the current MR, it is also true that [3] would also be the perfect time to start working toward some future MR. The fact that the MR and MC take place at different times is irrelevant. They already do with Bitcoin.

( Did you know that Bitcoin’s PoW reward is unspendable for 100 blocks? This is because, if orphaned, these coins vanish completely. Also, the miners are most-able to doublespend, so it’s wise to keep an eye on any coins that they definitely-own. )

Randomness

It is also true that, by the time [3] rolls around it would be too late to “grind” through random results in quick succession (until you find one that gives you the MR). Of course, [3] would also be the perfect time to start grinding through random results in quick succession, until you find the result that gives you the future MR. That’s already how Bitcoin works, in fact.

( Did you know that Bitcoin uses extremely strong randomness to select the creator of the next block? The randomness discourages collusion among block creators, making double-spend attacks unreliable. The randomness is so strong that no one can predict who will find the next block, or even [exactly] when it will be found! )

Making The “Work” Useful (Won’t Work)

“We will re-use the PoW as a heater…”

First, reusing work is always a smart idea; second, humans do need heat. Third, such an arrangement is highly conducive to Bitcoin’s goal (of achieving a Bittorrent-like resistance to coercive manipulation).

However, what is the effect on the MC and MR? Instead of an expected ($100 BTC) per x hashes, we’d move to ($100 BTC) + ($5 worth of heat) per x hashes. If $100 were previously being spent (at the hardware-efficient frontier), spending would be drawn upward toward $105 (eventually Bitcoin’s difficulty would adjust). Inefficient miners (those who didn’t use their waste heat) would be put out of business, but the total spending would still equal $100 (producing $95 BTC + $5 Heat).

The “Mining Heater” is just another increase in hardware-efficiency, resulting in a higher difficulty and an increase in ( energy_used / block ).

“The proof of work won’t just be double-sha-256, it will do something useful for society, like finding prime numbers…”

The logic of this argument is perfectly sound. Miners wouldn’t get money for finding large primes, so it would not increase their MR, so it would not increase their MC. But we, socially, get extra benefit, but total cost for “us” doesn’t increase. This is the externalities argument above.

First, the argument is ridiculous because Bitcoin is already doing something useful for society (mining wouldn’t be profitable if it wasn’t). Mining creates the network we know and love; Miners don’t share in the marginal benefit that I experience when I use the Bitcoin network (my privacy benefits or cost savings), or (more relevant) the value-added to society as a result of owning the option to use the Bitcoin network.

That someone would look at Bitcoin and think that, in addition to everything else it does, it should be edited to also help us find large prime numbers really makes you wonder who on Earth you are having a conversation with.

Secondly, this only works because the benefits are externalities, they are public and not owned by the miners. So there is no incentive for Miners to switch to such a system or even adopt such a system. The very thing which makes this scheme less-wasteful also makes it less-practical.

Two Big Examples: Tendermint and Delegated Proof-of-Stake

Ok let’s pick the ideas which have obscured their proof-of-work to a degree approaching incomprehensibility.

Example 1: Tendermint/Casper

Intro

Tendermint is a scheme where individuals can join the set of “validators” by locking away some of their e-cash. If they misbehave, they lose these “bonded” funds, and with enough not-misbehavior the network is brought to consensus “without mining”.

As far as I’m concerned, this scheme is identical to Bitcoin’s existing proof-of-work.

Ignoring…

First, this is an econ blog so I’m going to ignore all of the (more precedent) technical problems with this idea (novelty, scalability of signature verification, missing/ddos’ed validators), operational problems (how to bootstrap this when coin value is low, or save it if the value becomes low, how to create marginal benefit over Bitcoin), and cryptosystem problems (cheap long-range NaS creating millions of false chains indistinguishable from the main chain [save for one big doublespend], and imprisoning/killing everyone who tries to point out which chain is real) and instead I’ll just assume that all of it always works and scales and none of the ask-a-friends are tortured to death by the Mafia.

Validators vs. Miners

The problem is that validators receive ( NewCoins + TransactionFees ), an MR, and this MR induces a MC. While, in Bitcoin, ~25.01 USD worth of BTC are “wasted” by the Miners every 10 minutes, under Tendermint, ~25.01 USD worth of BTC would be wasted by the Validators every 10 minutes.

Nonproductive Investments Are “Wasteful”

What is the difference between the following columns:

| Unobscured PoW | Obscured PoW |

|---|---|

| Someone… Observes the potential to mine between $1500 and $2500 worth of Bitcoin at current conditions (exchange rate, transaction volume, coinbase inflation level, etc). Compares the potential return on this investment opportunity to that of other investment opportunities. Borrows $1800 of working capital, buys $1000 worth of mining hardware, and runs the hardware until it is fully depreciated, in the process spending $500 on electricity, $200 in lost labor-time, and $63 on interest. | Someone… Observes the potential to “earn” between $1500 and $2500 worth of Bitcoin at current conditions (exchange rate, transaction volume, coinbase inflation level, etc). Compares the potential return on this investment opportunity to that of other investment opportunities. Observes risk-free-rate of 3.5% and validation-bond rate of 4%. Borrows $47400 of working capital and invests this capital in validation bonds, in the process spending $1659 on interest. |

| Revenue of $2000. After expenses ($1763), $237 was earned (as “risk-compensation”). | Revenue of $1896 (4% of $47400). After expenses ($1659), earned $237 as risk-compensation. |

In the unobscured case, miners secure the network. Society only produces so many luxury cars, luxury shoes, mansions, etc, and each year the miners get some of society’s scarce resources (and other hardworking people do not). Some also goes to the upstream-associates of the miners (those who produce mining-hardware and electricity) as well as the downstream-associates of the miners (the owners and waitors of the miners’ favorite restaurant, preferred artists/charities, family and friends).

In the obscured case, it is those who own validation-bonds who benefit disproportionally. They get the nicer cars, their wives get the nicer shoes (or whatever).

Is “Liquidity Is Important” really so hard to believe?

I’m sure the economic concept of “liquidity” isn’t exactly a household term. But I thought that it was commonly understood that money is something you might need to have fast, and without much notice. Is it not common to keep a stash of emergency cash somewhere in one’s residence?

Sadly, our modern endless-ZIRP has ruined yet another generation of potential savers (“indirect capitalists”), but, ask your parents: you used to be able to buy something called a CD, where you locked money away for a period of time (6 months, 1 year, 2 years). For suffering this inconvenience, you got a higher interest rate (which the bank could provide as a result of its increased lending-potential). You could essentially “sell” any extra liquidity you had but didn’t need, and thus: scarce liquidity was allocated more efficiently across the whole economy.

And liquidity is an important thing, just ask Lehman Brothers, or victims of the Zerg Rush. If everything always went OK, those guys and their elaborate long-run plans would always win; but things don’t always go OK.

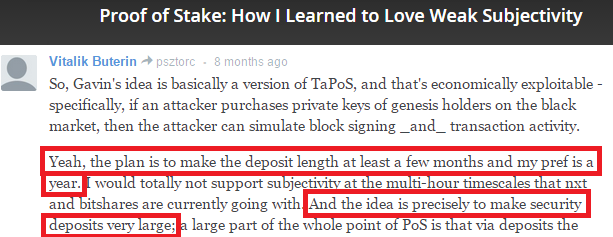

In return for sacrificing their liquidity completely (even CDs can be cashed out early -at penalty- whereas TM-bond-owners are entirely unable to get their money out of the system for YES an entire YEAR), the economy “gets” ““nothing””. The liquidity was “””"”wasted”””””.

Wishful Thinking

Some might ask “Doesn’t it all ‘cancel out’, somehow?”, “Is there really any damage done to society from having some of the money supply locked away somewhere?”.

No, it doesn’t cancel out, there is no damage done, all the PoW is a net positive (whether Obscured or Unobscured). Miners can only sell those BTC because the BTC-network is useful. Miners make a profit, chip-manufacturers make sales, utility companies make revenue, inefficient payment systems get updated/replaced.

Claims 1, 3, 4

On a Vitalik blog post, VB admits “One objection to long-term deposits is that it incentivizes users to keep their capital locked up, which is inefficient, the exact same problem as proof of work.” and then lists four “counterpoints”. Two are entirely irrelevant: [1] that marginal cost is not total cost (Vitalik is apparently measuring marginal cost per block instead of per work-unit), and [3] that the security deposits are safe (as irrelevant as saying “mining hardware is efficient”). The last, that [4] validators can be hit for the entire (capital) “stock” and not just the (operating) “flow”, has been false since Bitcoin-mining came to be dominated by ASICs and branded mining-pools (whose economic value would indeed be overwhelmingly destroyed in the event of an attack).

Claim 2

The second claim, that the locking-up of funds produces socially-beneficial price-deflation, is wishful thinking. It is not true that “less money supply is available for transactional purposes”; such a statement would describe destroyed security deposits. The only reason the validators freeze their money is to take it out later and buy something. If they wanted to reduce the money supply they’d have to destroy the money permanently; this destruction is the sacrifice of production which enables a higher standard of living for the non-sacrificers. Bonders, in contrast, enjoy a relatively higher standard of living in the future, only at the expense of today’s living-standards.

Monetary economics is probably the most confusing branch of econ, so let me explain this in three other ways.

Claim 2 (i) - Pick a lane!

First, “the price level” will only react to changes in the money supply (and, if certain derivative-markets are alive and well, only unexpected changes). This implies that, even if bonding changed the money supply (it doesn’t), as long as a constant quantity of money is out-of-play, the effect will be non-existent. If the supply changes, helpful deflation will be offset by (by the logic submitted, “socially-harmful”) inflation. Notice that at any frozen instant in time, no money is being “transacted”…if this ubiquitous not-transacted money created helpful price-deflation, then everyone who held cash would be doing it (not just bonded validators).

Either we consider the expected future flows (including bonds), or ignore all of them (and include nothing, using max(currency_supply)).

Claim 2 (ii) - Proof by Contradiction

Second, suppose prices really did react to money-freezing in a way equal to money-destruction. If 99.9% of the money supply were bonded, prices should fall by a factor of 1/1000 (as they unambiguously would if 99.9% of the money supply were irrevocably destroyed). However, anyone with cash (“liquidity”) can now go on an amazing buying spree. They can even pair up with the “rich-but illiquid validators”, to jointly “invest” in a new “project”: acquiring lots of cool stuff. These “projects” are more “profitable” than any non-financial projects (starting a business, opening a factory, car loans for new commuters), and the consequent rise in interest rates (the “price” of “liquidity”) will crowd those projects out, resulting in less investment, a smaller capital stock, and a poorer future for everyone.

Claim 2 (iii) - What’s wasted? Liquidity.

Third, it is clear that, if validators are going to earn enough BTC to buy, say, a Lexus, and society produces the same total number of Lexi, then someone else isn’t getting one. So, in order to actually be “cheaper”, Caspermint needs to enable society to produce more stuff (more Lexi).

Without mining, less electricity is used in mining, and less silicon is used in mining chips. Are these resources available for extra production? Yes. However, these “non-wasted” resources are offset by other resources which are “wasted”. PoW destroys energy/hardware directly and specifically, while Tendercast destroys liquidity vaguely and generally.

Let’s detour for a moment to talk about interest rates and the market for loans. Imagine you are a wandering hunter, famished after days of protein-less, salad-y, lame, vegetable-only forager-food, and you suddenly become aware of a juicy rabbit nearby. The demand curve shifts up. Your body gets excited: your breathing and pulse increase, scarce chemical energy is being loaded into the muscles, your mind begins to burn oxygen and glucose as it plans furiously to kill/capture the rabbit. Previously, there was no need to waste precious glucose (“liquidity”), but (your brain cells say to each other) if we bag this rabbit (today) we’ll all be chemical-energy rich (in the future) and, who knows, we might even be able to take some time off and rest, practice new skills, signal our evolutionary fitness/get laid. I mean, a hunter-gatherer-bioregulated-psychology can dream, right?

Anyway, under PoW, liquid resources (silicon, metal, concrete, electricity, time, effort [which could each be used for many things but by themselves aren’t very useful]) are drained and pooled into illiquid applications (the mining hardware and infrastructure, as well as the knowledge required to build, manage, and maintain the facilities, and the social relationships between all of the owners and their business partners [which are very useful for a specific purpose but generally quite useless]). Investors are, in essence, making a bet that “no other more-useful combination of these factors-of-production will come along” over their investment time-frame. So it is with Tendermint-PoW; the bonded funds are locked away and can’t be used for anything else; the bonders are making a bet that nothing better will come along. The waste is impossible to photograph (as it concerns things which have NOT happened but should have), but it is still there.

Under PoW the hunter-gatherer is wearing weights (and it is harder to catch the rabbit), under TenderPoW the h-g’s body can’t load glucose as quickly (and it is harder to catch the rabbit). Either way, fewer rabbits are caught. In fact: market forces, specifically interest rates, should always place society at a frontier where we are all indifferent between the two (if any project were freely over-beneficial, money would be pouring into it and interest rates would be rising, same for any consumption “project” which over-produced utility).

Finally, lasting differences between the two PoW are possible: PoW might be better for economic growth, SoftAltoid might be better for CO2 emissions. It is quite difficult to say. Less capital means that the future will be worse, and contain less technological/scientific progress, fewer abatement/sequestration technologies, carbon-alternatives, etc.

Flirting with the Mainstream

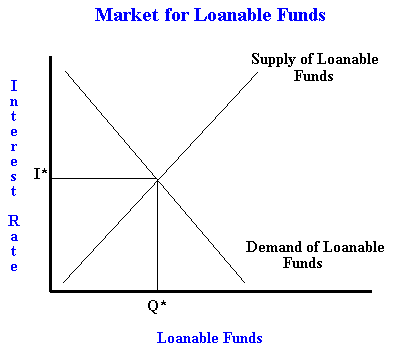

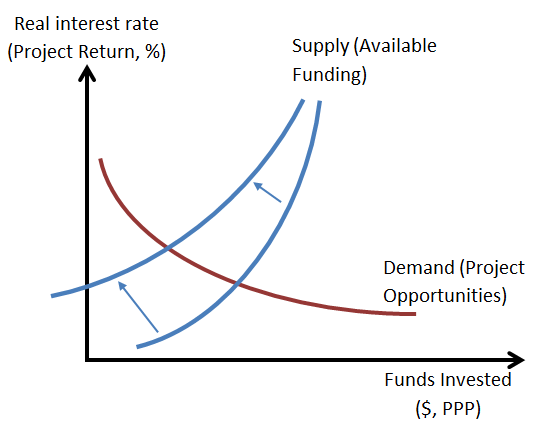

Break out your econ textbooks, here is a supply curve in The Market for Loanable Funds:

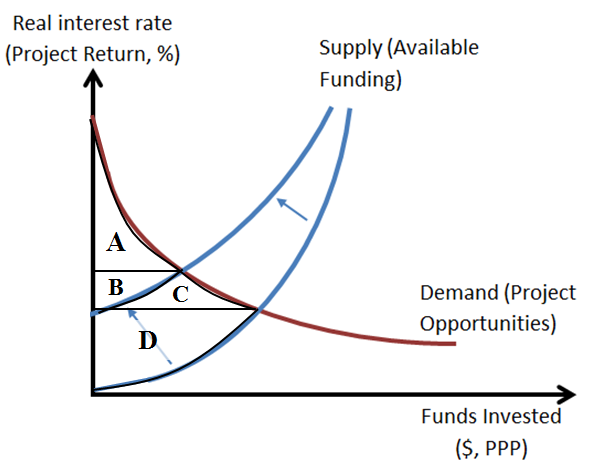

Now it is with the Supply Curve leftward-shifting to represent the “wasted” loanable funds on this “non-productive” investment.

Now here is the surplus (C and D) which is “wasted” on validation.

| Surplus Table | Before | After | Net |

|---|---|---|---|

| Consumer Surplus | A, B, C | A | -B, -C |

| Producer Surplus | D | B | -D, +B |

| Total | A, B, C, D | A, B | -C, -D |

All of the wealth in sections C and D has been destroyed…quod erat demonstrandum.

Example 2: Delegated Proof-of-Stake (DPoS)

DPoS is a plutocracy where people use (but, neither spend {“democracy”}, nor risk {“capitalism”}) their money to elect 100 senators, who sign blocks in a sequence and thus secure a nearly-P2P network.

As usual, we’re going to ignore all of the problems with this (that plutocracy implies same-wealthy-idiots-on-every-decision and inevitable decadence [unlike “rule of the experts” capitalism], that DPoS strongly concentrates wealth [and, therefore, protocol-control], that voters [even at the more-efficient corporate governance level] never seem to know or care about the issues they’re voting on, and that any conspiracy of 67 delegates can profitably double-spend without getting caught).

Instead, I’m just going to show that (again, for the Bitcoin issuance schedule) it is consequentially the same as Proof of Work.

In Theory

Theoretically, what is attempted is: [1] “Every non-attacker will know which 100 delegates are right for the job…”, [2] “…in a way that is not reliably subverted by human ‘work’…”, [3] “…and, since, attackers wouldn’t ever own >50% of the total money supply…”, [Conclusion] “…the network will always be safe.”

Obviously [2] is the deal-breaker, and [1] isn’t helping.

If you “get it” by now, I suggest you skip this section (to “The Coinbase-Rot Paradox”). However, because it happens to be a personal interest of mine, I’m going to write several paragraphs about how “voting” is only effective when it is cheap to cast an informed vote (which isn’t the case in DPoS).

Money and Politics

Votes are bought. Not directly (this would challenge the voter’s treasured self-delusions, and be a focal point for coordinated outrage), but indirectly through tax breaks, welfare, military action, subsidies, research grants, licenses, etc. Loudly, it is claimed that these all serve civic purposes (the reality is “some”), but the quieter subtext is: “a vote for Candidate X is good for your bottom line”. On top of that, there’s ad-spending and professional campaign management. Because election-competition is zero-sum, these activities cancel each other out and are net “wasted work” for society.

Is vote-buying a bad thing? Who really knows (considering the long-run coordination problems facing this species…)? For today’s post, who cares?

I’m not arguing that this is “good” or “bad”, I’m just arguing that it’s “true”.

Votes become easier to buy as the number of voters increases. Though it may seem innocuous to say “the more voters there are, the less each individual vote counts”, the statement is in fact a grave paradox. Eventually, the sheer quantity of voters guarantees that each individual voter is irrelevant – a balloon inflated to such a grand size, that the stretched plastic simply vanishes altogether. If 3 people vote, a single vote can swing a possible tie, but if 10,000,001 people vote, a tie probably won’t even occur (making each individual vote completely irrelevant). The voting process can be defeated entirely, by taking a small “critical mass of uninformed voters” and, to it, adding some self-fulfilling expectations of hopelessness.

If informed voting were cheap, these self-fulfilling expectations would be expensive to generate. Unfortunately, voting is not cheap, voting costs energy that most people won’t spend. This small detail means that any politician who can quietly use public resources to finance their bribes will always have an overwhelming advantage.

Wealth Isn’t Unequal Enough

What about the fact that DPoS votes with wealth instead of per capita? The improvement is insufficient: while wealth does distribute non-uniform (instead: lognormal or power law) a project aspiring to “world wide ledger” status will eventually have a very high quantity of people in each wealth-class; so many that casting an informed vote will still be (for each individual) a waste of time.

Voter apathy reliably strikes the more optimistic scenario of modern corporate governance. There, each share gets a vote, and disinterested parties can sell and abandon their need to vote altogether (impossible in DPoS). The ability of shareholders to elect the board of directors makes almost no difference; most shareholders don’t care enough to vote, and certainly not enough to learn-or-do-anything-about obviously corrupt phenomena such as executive pay, poison pills, empire building, golden parachutes, etc.

DPoS, like all voting, is not capitalistic. Capitalism is not about “one dollar, one vote”, it is instead “one dollar risked, one vote”. Capitalism requires the potential for gain as well as the risk of loss. With voting, gains for “good votes” are public, and equally and widely dispersed (no potential for private gain), and voting is free (no private risk of loss).

Back to Work: Scarce Cognitive Resources and Advertising

If learning who to vote for takes “work”, then, even absent bribes, voters will always be susceptible to “work”-based influence. In the US federal elections of 2012, SuperPACs raised and spent well over 500 million dollars. People don’t spend that kind of money unless they get something out of it.

Many studies document the effectiveness of political advertising (especially “attack ads”). Try here and then check the “users also read” sidebar. Recall that a positive correlation will suffice, no matter how small. Just as a single hash is unlikely to win a Bitcoin block, it may be the case that a particular ad-campaign is unlikely to win an election. However, the total spending is tethered to the total expected value of the kickbacks controlled by the elected party.

Disowning the Rents Doesn’t Destroy Them

Attempts to create a barrier between spending and result always fail, any leak in the work-barrier leads to total failure (recall that PoW-hashes are individually unlikely to win a block).

For example, in the US, citizens who are clueless of the MC=MR identity try to limit political advertising contributions to a certain spending level. Of course, as the ads are effective (MR), the MC will always creep back upwards. In this case the MC takes the form of SuperPAC ads, which buy the MR with MC, but have a merely-inconvenient detail that they can not legally coordinate with the candidates they support.

Sometimes candidates might be secretly appreciative of these ads, other times they may be genuinely frustrated. We’ll never know for sure, of course, but we do know that Gingrich lost.

If anti-corruption were as easy as “banning political spending”, our society wouldn’t have the problematic history it does. The founding fathers knew that the only reliable anti-corruption measure was to set up a limited government. By diminishing the MR, they knew that the MC (spent on corruption, lobbying , propaganda, etc.) would fall correspondingly.

I wish we could do that, but, as the next section will show, we cannot.

Does Voting Ever Work?

Voting works just fine (even very well) when the cost to casting an informed vote is zero, and the votes are aggregated appropriately (mean for a yes/no decision, median for values over a range). If votes are very easy to cast (from a smartphone or something), and the votes are only on preferences/values/priorities (which come from your own head, for free), voting will produce some reliable signal about which course of action would hurt the fewest people’s feelings. This signal could be a powerful, non-violent, society-organizing tool. However, in our case (of validating a blockchain’s consensus, amid attackers who will specialize in confusing voters), an informed vote is always going to be expensive.

Something To “Work” Toward(?)

I repeat, in order to ever distribute money in a way that does not produce endless zero-sum competition, the distribution has to be wholly indifferent to human effort.

It would take something like a permanent unalterable super-fascism, distributing X new coins each, only to everyone currently having an 18th birthday, and then forcing those 18 year olds to relocate and never contact anyone from their previous 18 years again. And even this might favor those people who (selflessly) sire many children (that they’ll never see again), and this is assuming that the inflation-tax drawdown can’t be evaded (ie, it is a perfectly efficient lump sum tax), that the currency-issuing-mechanism / government-itself can’t ever be altered or corrupted.

Now, as far as e-cash is concerned, to the very final consideration: the issuance schedule.

The Coinbase-Rot Paradox (“Less is more.”)

Decreasing the quantity of coins released in each block, actually increases the total economic value released in each block. Premining all of the coins encourages work across blockchains.

The Units of Money are Fractional

With money, “what other people own” affects you. If I were magically offered 1 Steinway Grand Piano, on the condition that a bunch of other people would each get 1,000 SGPs, I’d take the deal. I’d take disproportionately offered mansions, televisions, health, magic powers. I might be disappointed or confused, but I’m looking out for #1, that’s me, and anything free I’ll take.

This isn’t the case with money: when money is offered to someone else, my purchasing power decreases. It is as if some of my money has ‘rotted’ away.

Notice that, with money, multiplying the total quantity by some factor changes nothing (in fact, one could do this in the US by simply relabeling “dollars” to “cents” and multiplying by a factor of 100). Any uniform quantity-changes are just a translation from the word “dollars” to some other invented word. It affects nothing in reality.

It is precisely because uniform changes are meaningless, that non-uniform changes are meaningful. If you work hard all day, and are paid $100 for your work, and someone else prints $100 for no effort, you have a diminished willingness to accept $100 for tomorrow’s work.

You care about the “% of the money supply” that you just got. You want it to be high. Everyone else wants it to be low.

“What if we only offer 5 BTC / 10 minutes instead of 50? That’s 10x cheaper!”

No, I’m afraid it isn’t. Reducing all of the amounts by 10x has no effect whatsoever (the equivalent of pricing everything in dimes instead of dollars).

What is possible, however, is to manipulate when these fractions of the money supply come into existence. Just as one is happier receiving $100 tomorrow vs. $100 a year from now, it is more painful for a $-holder to endure $100 printed tomorrow vs. $100 printed a year from now.

But this is a paradox: a lower “% of the total tokens” released today would seemingly decrease the block’s MR (the number is smaller). Yet, by releasing more %-coins in the future, the money ‘rots’ slower, and therefore this money-type is more valuable (the quality is higher), increasing MR.

“Like NXT/Bitshares/Ripple we’ll release all the coins upfront. Zero per block…no MR, right? “

Wrong. A terrible idea, and still enslaved to MC=MR.

I’ve previously written about how such a decision is fatal to crucial monetary network-effects (the second half of my original post). It also appears to have no natural analog (absurdly dangerous). Thirdly, it concentrates the coins in the hands of a very few people, making for an extra-volatile start (as the exchange rate increases, all of these early-adopters become ultra-rich and are tempted to sell…at once). If anyone expected NXT to succeed, the early-adopters would have to carefully guard their identity.

But have we at least achieved MR = MC = 0? No “wasted” work?

No. The 100% premine itself constitutes a huge MR at time=0, and it will be fought over like any other MR. The MC=MR problem has been concentrated into a single tiny block, and spread sideways across multiple blockchains. Since, the eye can only focus on one thing, the work (the marketing involved in getting a community to switch chains) is overlooked, just as in our first example of stake grinding.

Ask yourself: Are Ripple and Stellar actually two separate blockchains? I say this dual-chain phenomenon is actually a nothing-at-stake attack against a single lucrative block (of an eigen-chain that can easily hard fork between Stl and Rip). Are Counterparty, NXT, Bitshares, NEM, etc. actually serial attempts to “add” “new” “features” to Bitcoin? I think they are desperate, self-ignorant, longshot attempts to knock the “Bitcoin” out of HyperBitcoin-ization and replace it with something else.

There is already a lot of “Blockchain, not Bitcoin” talk going around, as well as concerns that it is “too late” to get into Bitcoin. These concerns prompt new users to consider creating their own (new) system. Bitshares ignored NXT’s 100% premine. Ethereum ignored Bitshares. NEM will ignore all three, and what comes after will ignore those. The 100% premine takes anyone who wants to build something new, and erases their entire benefit for doing so in a way compatible with the existing system. It takes the creative innovators and kicks them out, forcing them to compete for winner-take-all network effects (…you might as well grab a net and head to Southern Australia if you want a Black Swan this badly). This competition for dominant chain is the Proof of Work, a version of stake grinding with even less focus and an ochlocratic / marketing-based security.

Whereas quickly-inflating coins “rot” (lose value) individually, slowly-inflating coins “rot” collectively, as the entire network “walls itself off” before it can mature (and it instead must “work” against its many competitors).

Balancing the Rots

Blockchain security is not the main function of Bitcoin’s PoW. Instead, PoW serves to delay the release of the coins such they they are still cheaply available when potential-network-joiners first discover the project (what some complain as today’s problematic “dumping” by miners).

Everyone wishes they found Bitcoin earlier, but earliest-take-all implies the network can’t grow.

This problem (“Will anyone want to use the network?”, “How can I get the protocol to pay for its own marketing, development, etc?”) is orders of magnitude more important than some boring technical detail about Byzantine Generals. A broken system is useless, yes, but it is a heck of a lot easier to get something to work, than it is to get something to be useful.

Conclusion

“Proof-of-Work” exists because money is being created. It is, then, impossible to “create a new form of money” without invoking Proof-of-Work.

Satoshi’s design insight was to channel that inevitable work into a cumulative process, to optimally stablize a peer-to-peer clock in a cartel-resistant way.

Kudos

The concepts in this post were, long ago, outlined by many others. One can’t write about PoS without mentioning Andrew Poelstra and Greg Maxwell, who lay the foundation for this generalized counterargument.

comments powered by Disqus