When it comes to protocol upgrades, we need better words.

Simply

My proposed new terms are:

- Hard: Creates a new network.

- Mean: Forces miners to constrain everyone on an existing network.

- Loud: Creates ecological discrimination towards those who don’t upgrade.

- Friendly: none of the above.

Motivation

The goals of this post are:

- Help people understand each other, wrt. protocol changes.

- Point out how soft forks can become hard, and vice-versa, to help people realize what they should actually be caring about, instead.

In general, I feel that clearer language helps all of us be aware of Bitcoin’s attack surface. The more aware we are, the better we can prepare.

I will be expanding on my previous comments here and this section.

Does it Matter?

Often, conversations of this kind are Talmudic hairsplitting, at the expense of practicality. Usually (when we refer to Soft, Firm, Evil, or Hard forks), a clever person will grasp enough context to decipher the speaker’s original meaning.

However, in the context of a contentious scaling debate, fraught with misinformation, motivated-reasoning, and outright propaganda, it might be worth the extra effort to be as-clear-as-possible about what you mean.

( But hey…they’re just suggestions. Take ‘em or leave ‘em. )

Current Problems

Full-time Bitcoiners work very hard to agree over the ‘softness’ of a fork (or of equivalent notions, such as how many hard/soft forks we’ve had in the past).

Disagreement is even more pronouned for proposed future changes. And, of course, disagreement is highest over the relative costs, benefits, and risks of hard and soft forks.

Why does this conversation always progress so little?

1. Ambiguity

The existing definition (that soft forks ‘tighten’ the rules, and hard forks ‘loosen’ the rules), is more ambiguous than it might appear.

For example, a soft fork would include all of the following changes:

- A fix for a severe bug that allowed someone to counterfeit 184 billion BTC.

- Support for a new feature, CheckSequenceVerify (and thus support the Lightning Network).

- A freeze the money in Address X, forever (and, by the properties of money, cause value to be redistributed to others).

- A new policy, to only mine empty blocks forever (this change is indistinguishable from a 51% DoS attack).

- A policy where no one is allowed to broadcast to the chain at all, until they upgrade their software.

In other words, the current usage of ‘soft fork’ includes a wide range of phenomena; it lumps bugfixes, upgrades, and attacks into the same cateogry. This make it hard to talk sensibly “about soft forks” (as so little of what is said will really be ‘true’ for all soft forks).

2. Poor Logical Foundation

As the 5th bullet point (above) reveals, the soft fork label is not only unclear, but it is also self-contradictory.

In fact, out of necessity, others have needed to move Bullet #5 into a new category: the ‘evil fork’ (what I will call a “100% Mean” fork).

In the evil fork, the protocol rules are altered to become informational substrate for arbitrary data (and, upon this blank slate, a new protocol is written).

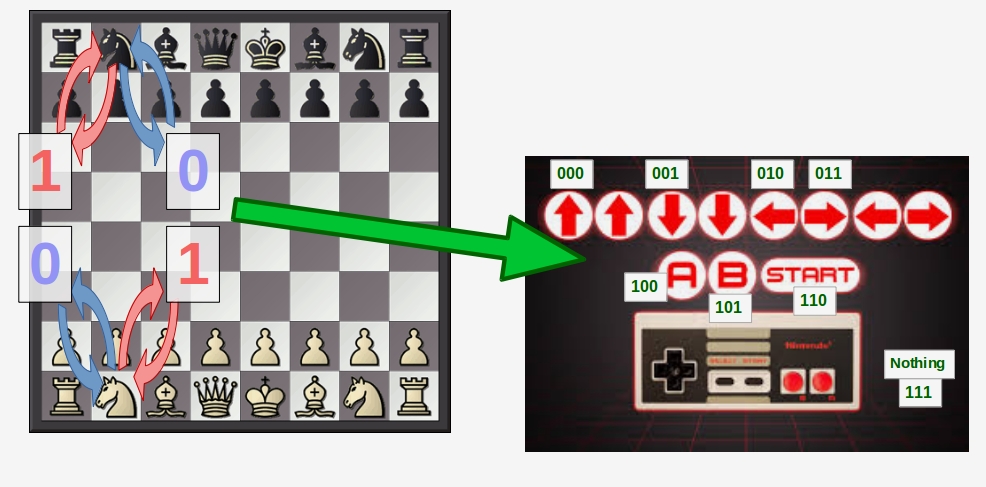

Let me elaborate with a non-Bitcoin example. Consider “Chess II”, which we’ve implemented by soft forking “original Chess”. Chess II might only allow the players to move their queenside knight, to one of three squares (initial position, left, and right).* By doing this the players can encode bits of information – “0” for left, “1” for right. In so doing, they can signal their moves for any other game – even something like Checkers, Connect 4, or (by advancing frame by frame) Starcraft II.

How did this happen? Well: the “rules” of “chess” ceased to define a game, and instead functioned as informational substrate – they are the paper upon which information was written.

The result, is that we have a way of ‘loosening’ the rules…by tightening them.

* Ordinarily, standard chess rules would quickly trigger a draw, via threefold repetition (and/or, the 50 move no capture rule). But the problem is trivially avoided by forcing the players to play multiple games in a row. (Moreover, we can lengthen games by forcing all other pieces to increment in a predetermined sequence, or we can simply force both players to always decline the draw.)

The Culprit

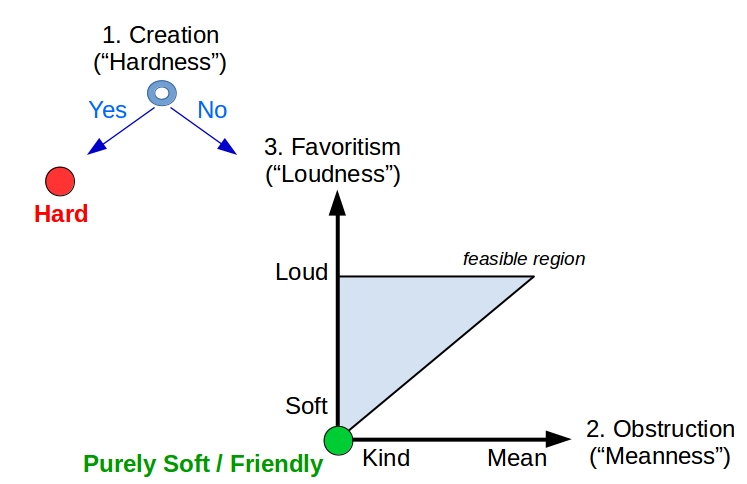

In my opinion, these problems are largely the result of imprecise terminology. Often, “softness” is used to describe (at least) three separate ideas.

- Is a new protocol created?

- To what extent are miners now obstructing users, all of the sudden?

- To what extent do users feel indirect pressure to upgrade?.

Solution

I therefore propose that we expand our existing language:

- Hard Forks (vs. non-Hard)

…by further dividing the non-Hard category as follows:

- Mean Forks (vs. Kind)

- Loud Forks (vs. Soft)

All Mean forks would be Loud, and all Soft Forks would be Kind. Kind Forks, however, are allowed to range from Loud to Soft, as shown here:

Soft Forks score the lowest of all, on three measurements. These measurements correspond to [1] creation, [2] obstruction, and [3] favoritism (the three enumerated points above).

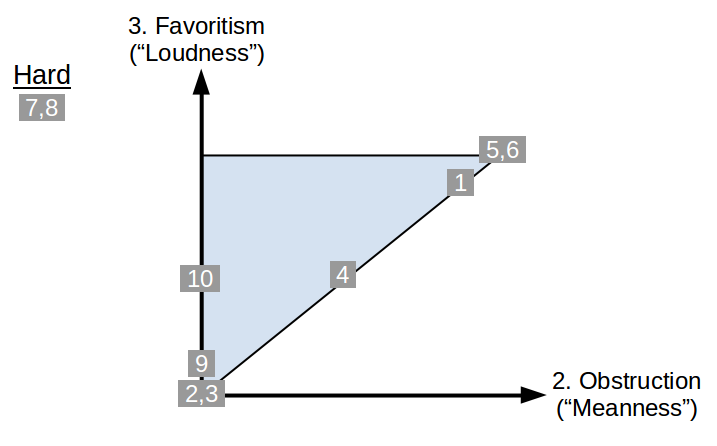

I’ve plotted several upgrades on the triangle graph, to give you an idea what I mean.

…and here is the corresponding table:

Table

| No. | Item | Hard? | Mean? | Loud? |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | When Satoshi imposed the infamous 1 MB block size limit. | No | 95% | (95%) |

| 2 | Sipa’s limitation of the coin supply to 21 Million. | No | 0% | 0% |

| 3 | The value overflow fix. | No | 0% | 0% |

| 4 | The s-value discouragement. | No | 49% | (49%) |

| 5 | A version of Bitcoin where blocks are always empty. | No | 100% | (100%) |

| 6 | An ‘Evil Fork’ upgrade. | No | 100% | (100%) |

| 7 | March 2013 Upgrade Bug | Yes | (100%) | (100%) |

| 8 | Bitcoin Classic | Yes | (100%) | (100%) |

| 9 | Adding support for CSV | No | 0% | 5% |

| 10 | Adding support for SegWit | No | 0% | 40% |

| 11 | Satoshi’s change from ‘longest chain’ to ‘heaviest chain’. | * | * | * |

Discussion

The Hard Fork Creates an Altcoin

I will save my major complaints about hard forks for tomorrow’s post.

For now, I will just point out that, if ‘Altcoin’ is defined as “a cryptocurrency which is not Bitcoin”, then a hard fork of Bitcoin always creates an Altcoin.

For example, consider a “spinoff” where we create “Bitcoin 2.0” (as a hard fork of Bitcoin 1.0) which inherits the UTXO set of 1.0. Everyone could upgrade, and we could all live happily ever after.

However, if the spinoff succeeds, we have discarded Bitcoin 1.0 as a failure and started over with something new. We will fail to define Bitcoin at all, unless we define it as “the set of X rules (and Y genesis block), and all subsets of these rules”. Else, the definition will either entangle [a] itself in tautological circularities (such as “Bitcoin is what most people think Bitcoin is”), or [b] it will include obvious non-Bitcoin, such as the CLAMS Project (or worse it will include every blockchain). Neither of these two outcomes is unacceptable.

What Mean Forks Remove: Functionality

The software of this quad robot at 6:55 allows it to reach any point in space, even if some of its appendages are removed. If we assume that ‘yaw-flying’ is one of the many algorithms programmed into the ‘original’ quad, then the decision to disable a few wings (for whatever reason) is not a ‘mean’ fork with respect to range. While the quad has lost one degree-of-freedom wrt motion (yaw), it can still reach any location in the room. Therefore, the three dimensions (of range) that we care about are unaffected. To restate: losing two wings is Mean wrt yaw, but Kind wrt range. Losing two wings is also Mean wrt flying mode, cargo stability, battery life and (probably) altitude, top speed, etc.

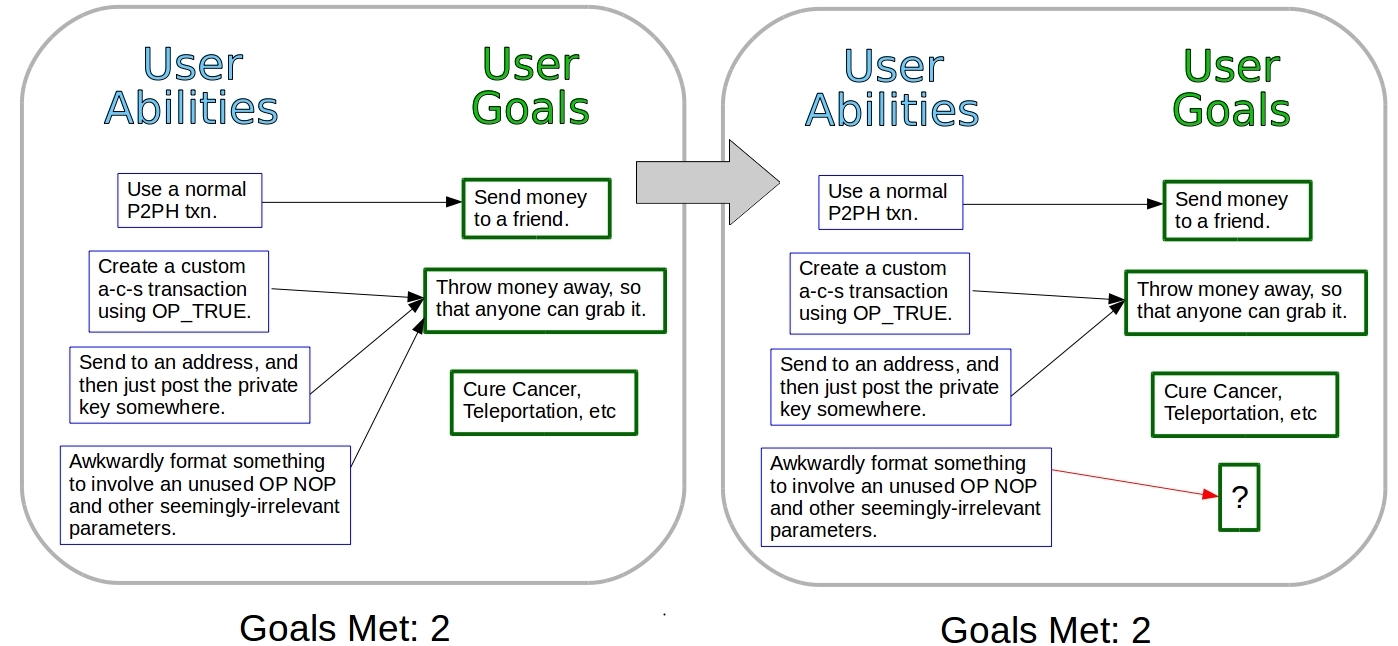

To be mean, you have to be prevented from acheiving a goal with your present software. This is why re-purposing the ignored OP NOPs to create new opcodes is 0% mean.

These protocol upgrades do filter (ie, “censor”) the users: they can no longer broadcast certain anyone-can-spend txns, if these are of a certain structure. However, the upgrade does not prevent a stubborn non-upgrader from achieving the same goal as before. There are hundreds of still-valid ways to create an anyone-can-spend txn. Moreover, the upgrade does not interrupt those ways which were in popular use at the time of the upgrade.

Figure: since the “goals met” metric has not decreased from 2, the upgrade (left-to-right) is not mean.

The value-overflow bug itself removed functionality (removed the ability to receive value), and the functionality created by the bug was not used by anyone before its discovery. It is therefore not Mean. The s-value fix, however, prevented affected users from sending money via signatures, until they had upgraded. Pre-upgrade, users could only receive money. It was therefore almost half Mean.

No ‘Extra Credit’ For New Functionality

‘Meanness’ measures the number of options destroyed. It intentionally IGNORES any “new” options that are brought in to replace it, even if those options are “identical”. This is because the labor involved in checking all of these rules (to know if you’ve been paid), is the entire purpose of the protocol.

So, to have a user redo it, out-of-protocol, would be a contradiction. Call it the “Reductio ad PayPal”.

In this way, the ‘evil fork’ (described above) is just 100% mean (and indistinguishable from a 51% attack of empty blocks).

Loudness is About Users, Not Miners

When the Bitcoin miners coerce behavior directly, this is Meanness. However, if miners merely induce an unwelcome change, this is mere Loudness. For example, we might pass a law banning VCR rentals, which would close down Blockbuster (Mean to Blockbuster), or we might pass a law allowing Cable to sell video-on-demand, which would result in Blockbuster hurtling towards bankruptcy (Loud for Blockbuster).

SegWit is Loud, because it causes ecological changes to the network in a few ways. The most important is that Alice may wish to send money to Bob, but Bob is only configured to use the Lightning Network. Alice is then pressured to upgrade, in order to send money. Another source of Loudness is that, when Carol wants to send money to Alice, Carol may want to use SegWit (which offers a fee discount under many conditions), which will put pressure on Alice to upgrade, so that she can validate these kinds of incoming payments.

(Miners, however, should always accept anything that pays a high fee/kb, regardless of its format.)

None of the Above

Finally, consider:

- The “Friendly Fork”, which is neither Hard, Mean, nor Loud. (Notice that, a fork cannot be Kind unless it is not-Hard, and a fork cannot be “100% Soft” unless it is simultaneously 100% Kind.)

- Satoshi’s modification of the chain selection rule from ‘longest’ to ‘most work’. This “upgrade” technically did not change anything about block validity (ie, which blocks were-or-were-not valid). In fact, in principle, it was a purely cosmetic change…only displaying one up-to-date history, instead of another up-to-date history. It was, of course, a crucially important change; but -in a quirky way- it was not a fork of any kind (IMHO).

- Similarly, reorganizations (big or small, intentional or otherwise), aren’t really ‘upgrade forks’ either. In this way our terminology is particularly counterintuitive – the only ‘upgrade fork’ which literally “forks” [ie, actually splits a blockchain into two] is the Hard Fork. Meanwhile, our real-life chain regularly splits into two (ie, stale/orphan blocks), and later remerges, but these events are not considered ‘forks’ anywhere in this article (nor by most people).

- Imagine an ‘inverse soft fork’ where a permanent >51% hashrate group decided to drop support for the most recent soft fork. From one vantage point (those running the most up-to-date software), this would be an unabiguously Hard, but from other vantage points (those running any other software) the fork would be 100% soft. It is purely Hard for some people and purely Soft for others – very curious!

Conclusion

I hope that this set of terms is useful.

In particular, I hope that it clarifies the status of the ‘evil’ fork, as indeed evil. And I hope that it allows users to complain about “loudness”, without forcing them to also complain about “soft forks”.

comments powered by Disqus