A hashrate-majority can easily defeat a UASF. Moreover, they can do so without inviting retaliation, because upgrades do not generalize from the particular to the universal. The UASF is not only ineffective, but it can also result in loss-of-funds.

Summary

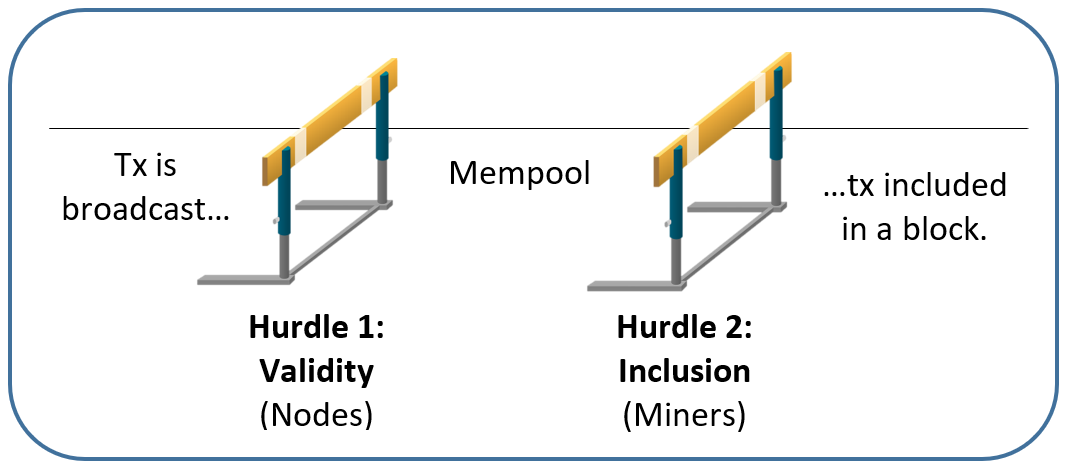

As most people know, all Bitcoin transactions are checked for “validity”. But what is overlooked (in the case of the UASF) is that they are also checked for “entrance” (ie, for inclusion in a block).

A soft fork can tighten the validity constraint as much as it wants, but miners have sole and absolute control over the entrance constraint.

If there is anything unique or identifiable about the txns in general, miners can simply prevent them from ever appearing in the block in the first place. Then, those txn will never be checked for validity by anyone, and the intended chain split would never occur. SegWit, for example, would be filtered from the longest chain, and the longest chain would be the only chain. SegWit would be nominally ‘activated’, but de facto unusable.

Since UASF upgrades will always have something unique or identifiable about their txns, the entire UASF concept is logically flawed.

Kudos

This is the problem with BIP148 that I originally mentioned earlier in May. As I’ll demonstrate, it was important to wait a little while before publishing it. Two people emailed me (actually 1 twitter + 1 slack) with the answer on the same day that I brought it up, kudos to them.

Nick ODell previously identified this issue all the way back in March, although he mistakenly implied it was a UASF, and implied that it should involve bit-signaling (it could, but probably should not, because this doesn’t help the attacker and may hurt him [in the form of false signals]). Shaolinfry chased him off as did David Vorick by dismissing his argument as “simply a 51% attack”. A lot of this article will be about why they are wrong about that.

But first I will explain the UASF Contradiction in detail.

Review

Forking and Goals of UASF

Classical upgrades to Bitcoin have relied on miners – the “Miner Activated Soft Fork”, or MASF. In response to reluctance upon miners to upgrade to SegWit, a new upgrade type has been proposed. It substitutes the “51% hashrate requirement” for a requirement of “economic majority of users”.

It accomplishes this substitution by using new software which forces a split, which results in two different networks. Since both have high difficulty (and each, therefore, are expensive to mine), miners will be losing money each time they choose to mine a block on the less-valuable chain. The strategic logic of the UASF, is that the New Chain will trade for a higher price, thus forcing “51% hashrate” (in fact, 100% hashrate) to join it.

The SegWit UASF Example

Consider these transactions:

1. tx1 -- "Setup"

2. tx2' -- "Compliant"

3. tx2'' -- "Non-Compliant"

tx1 selects inputs (A,B), and pays to outputs (X,D), where X is a SegWit output.

tx2' selects inputs (X,...), and pays to output (E) via novel SegWit rules.

tx2'' selects inputs (X,...), and pays maliciously to (Z) via exploiting the 'anyone can spend' quality of unactivated rules.

The goal of UASF is to have all tx2s be of the “Compliant” form, and have none be of the “Non-Compliant” form. It does this by forcing all “Non-Compliant” txns onto a different chain. The UASF then hopes that this different chain just goes away, or dies, which to its credit it is likely to do: the new chain has greater economic utility (it can be used for just as many things as before, plus some additional things), and so it can be assumed to have a greater market value, and can therefore be expected to prevail.

The Problem

The problem is that a 51% mining group can simply filter out all versions of tx2, whether Compliant or Non-Compliant. Furthermore, they can orphan any block which contains a tx2, of any kind.

They can do this easily, and in a few ways. Perhaps the easiest way would be to examine the diff between new and old software code, identify the SegWit logic, and manually set these txns to always be invalid, or to require them to pay an infinite tx-fee.

This is possible because the “old” consensus rules are globally known, as are the “new” consensus rules. For all nontrivial soft forks, there must be something to enforce, and there therefore must be something identifiable about the fork.

The effect of filtering the tx2s is to de facto prevent the UASF from succeeding. It does this by preventing a split, while retaining control over the heaviest chain.

In a SegWit example, no one would be able to use the SegWit outputs, so SegWit would just not exist. Miner would trivially set their Is_SegWit_Activated flags == TRUE, as required by BIP148 (creating the appearance of activation), but it does not, in practice, make any difference to the user.

Instead of SegWit not-being-enforced, it has simply been censored from the network. If we imagine two worlds, “A” where SegWit is enforced, and “B” where SegWit is unenforced, then this ‘censorship attack’ most resembles a situation where no one has every tried to use SegWit, at all. We cannot tell if this no-SegWit world more resembles World A or World B; we have no evidence either way.

We might all this technique “Anti-UASF”.

Scope of the Problem

Some UASFs are immune to the Anti-UASF.

A soft fork can be safely UASFed if it operates at the block level, or applies to all transactions equally. My conjecture is that all soft forks of this type will be bugfixes, because they represent cases where we want to take unexpected annoyances and totally remove them from the blockchain system. For example: BIP 42, the value overflow incident.

In contrast, if the fork operates at the level of individual txns, it is vulnerable to Anti-UASF. My conjecture is that all upgrades are of this kind, because upgrades will be about allowing users to choose to do previously-un-doable things. For example: all new OP Codes, SegWit, sidechains, and even softfork-like upgrades such as near/compact blocks, IBLTs and so forth.

Variations

Miners might implement Anti-UASF in a number of ways. They may:

-

…explicitly block all the transactions that have SegWit inputs. This would allow the 51% Miner group to laugh, as SegWit users throw their money into what is essentially a black hole, where it will be trapped forever. This would be most effective, if miners announced their intention to do this well in advance, and if they could credibly commit to unfreezing the funds after their “labor strike” is over. It is also probably the easiest variation to implement.

-

…use a “refunds only” policy, which allows users to spend SegWit inputs back to (one of) their “from” addresses. For example, if tx_S selects inputs (A,B) and pays to (X,C), then the only valid spend of input X would be to return it “to” A (ie, by locking it under the same script, or same conditions – we might insist on sending to the very first input, to avoid CoinJoin-like multiparty maneuvers). It can be assumed that the owner of X is also the owner of A, or alternatively that owner(X) can easily find owner(A) and demand an alternative payment (as they are recent counterparties). The affect of this is to minimize collateral damage (ie, make it so the SegWit-killer only kills SegWit itself…and not SegWit users/testers/promoters), thus making it more difficult for Upgraders to retaliate.

-

…attempt to prevent users from sending to SegWit outputs. In other words, try to block the tx1s instead of the tx2s – moving the attack backward in time by one txn. This might be done by watching for Bech32 outputs, or for different script-size-efficiency. Such monitoring might require a serious engineering effort, or may ultimately be impossible (if spends-to-SegWit can be hidden), but this route would be the most effective of all. One ‘quick and dirty’ method, to approximate this, would be to ban all spends to P2SH outputs (of all kinds, SegWit or otherwise). This would work, but it would also have the collateral damage of preventing people from sending to P2SH addresses. But fortunately [for the Anti-UASF miners], users could still get their money out of any P2SH address they own, in this case.

-

Even with <51% hashrate, miners can still make life difficult for SegWit users by charging extremely high fees for payments made from (or to, but same problems as #3 above) SegWit outputs. If #1 represents a “strike”, then this (#3) could represent a labor “slowdown”.

“Just” a 51% Attack

The Opposing View

When confronted with this idea, Shaolinfry [creator of UASF]’s response was as follows (emphasis added):

Fundamentally, what you have described is not a UASF, it is a miner attack on other miners. 51% of hash power has always been able to collude to orphan blocks that contain transactions they have blacklisted (a censorship soft fork). This is clearly a miner attack which would escalate pretty rapidly into a PoW change if sustained for any time. ... Of course, anything is possible, but game theory and incentives seem to suggest that any tantrums would be at most, short lived, if lived at all. Mining is an extraordinarily expensive endeavour, which is the basis of the strong assumption of Bitcoin that PoW/revenue incentives will keep miners honest. If that assumption is broken, Bitcoin has bigger problems.

I parse the counterargument as follows:

- The Anti-UASF is a “miner attack”, and all “miner attacks” lead to a “PoW Change”. Since miners don’t want a PoW change, then miners will never want to Anti-UASF.

- The Anti-UASF is a “tantrum”, and tantrums are “short lived, if lived at all”. This is because “tantrums” are an example of “[dis]honest” behavior (where “honest” is defined as “maximizing revenue”), and we assume that “PoW/revenue incentives” will keep miners honest.

But I don’t think these are true. Let me tackle it piece by piece.

1. The PoW Change

In this part of his argument, Shaolinfry admits that the only recourse users have is the PoW Change. The PoW Change is a so-called “nuclear option” and it cannot be used lightly.

A PoW Change is a hard fork1, which means that it is fundamentally an act of persuasion. Ie, it is an act of “governance” or “community organizing” or “politics”, and not an act of “engineering” or “science”. In a hard fork, we must persuade users to leave the old chain and join the new one.

But one of these things is much more persuasive than the other, if you ask me:

- “Miners have unexpectedly gone back on their word! Funds have suddenly been lost/frozen – consider yourself lucky that it didn’t happen to you, this time…but you might be next! Our beloved network lies in ruins, which was working perfectly fine until miners attacked it. If we work together, we have our best chance at creating a new network that restores Bitcoin to its former glory.”

- “You there! I need you to spend your valuable time helping me with my problem. Also, you may lose money, or this might be embarrassing for you. But hey, if we all just work together, then hopefully we can maybe allow the network to do some new thing, a new thing that maybe I can explain to you but that you probably won’t understand but trust me it’s great.”

The 51% Attack and Anti-UASF are really quite different:

| The 51% Attack | Anti-UASF |

|---|---|

| Could affect any user. | Only affects the users who opt-in. |

| Strikes without warning. | Is an inherent risk to the UASF; 100% forewarned. |

| Results in loss of funds – network is useless. | Results in status quo – network is unchanged. |

| Initiated by miners. | Initiated by [some] users. |

| Implies that miners will no longer facilitate a payment network – miners are useless. | Implies that miners will not allow users to make arbitrary changes to the protocol – miners promote stability. |

We could generalize the difference as follows: in the 51% attack, the “bad result” co-varies with “the miner’s decision to find ‘strange’ blocks for everyone”, but in the Anti-UASF, the “bad result” co-varies with “the user’s decision to create new tx-types that only affect him”.

And it is therefore difficult to attribute the Anti-UASF “badness” to the miners. Users who wish to avoid molestation by Anti-UASF can do so easily – they just need to decline to upgrade, until it has miner support. The 51% attack can affect you, but the Anti-UASF really can’t…not unless you let it.

I earnestly question whether or not Shaolinfry or David Vorick have actually imagined, in their minds, the enormity of the task that would be ahead of them. It would be to go door-to-door to persuade people to hard fork, in order to activate SegWit. They would have to know that they would not be able to reach everyone, because some people are strategically unreachable. Third parties would accuse them of starting an Altcoin. People would ask them “If we are hardforking anyway, why don’t we just add XYZ feature while we’re at it?”, opening up a negotiation that would drain everyone’s energies and potentially last forever. They’d have to pick the PoW algorithm, and the new difficulty; they’d have to win over exchanges, perhaps. There would be politics and drama associated with every choice. Meanwhile, regular users (who, by definition, are getting along just fine without SegWit) would feel annoyed and harassed by this process. And some users would proudly reject the new coin, either because they just don’t like SegWit, or because they prefer that bitcoin change as little as possible. Even if all of the above conflicts are magically resolved, users will be wondering if they are on the hook for an unbounded number of upgrades of this kind. For these, they likely do not have sufficient patience. And finally, such an action will alienate the miners who were originally loyal to you – BitFury George will not be happy!

Contrast that with a case where users decide to hard fork, in the wake of an actual 51% attack (one involving a large reorganization). There will be no door-to-door campaign, everyone will already know that a serious change needs to be made, because the network will have already reached a fully-ruined and unusable state. The question of whether or not the New Bitcoin is an Altcoin would be a moot point. There would be no lengthy negotiation, as a critical mass of people would terminate it at “change the PoW only, and launch as quickly as possible”. The quick launch would prevent drama from festering. The market would quickly select the successor-coin, arbitrarily if necessary. All users would embrace the new coin, because it is actually more similar to the old coin than the old coin is itself! There is no confusion over the “hard fork conditions” – everyone understands that HFs are to be done as infrequently as possible, but whenever necessary.

To me, Shaolinfry’s hardfork seems very similar to past failed hardforks, including XT, Classic, and Unlimited. In those cases, some group of people complained about their own problems, but not enough other people cared. People don’t care about your problems; they only care when there’s a big emergency that might affect them.

The comparison reminds me of the opening to s07e14 of The Office, when Ryan and Kelly get divorced and then demand that everyone take sides. “Who is on my side?” Ryan asked. No one raises their hand. “And who…”, Kelly says smugly, shooting Ryan a superior look “…is on MY side?” She turns to look at everyone, but no one raises their hand for her either. Everyone is just busy doing their job and no one cares. As far as everyone else is concerned, Kelly and Ryan are both losers and no one pays them any attention.

We might draw a distinction between a “universal” attack and a “local” attack:

- Universal – it affects everyone, even people who are not currently complaining.

- Local – it only affects the people who are complaining.

If an issue is Local, you can safely ignore anyone who complains. But for a Universal issue, you can not ignore the person who is complaining – you will thank them for warning you! And in turn, other people will thank you for warning them (which you are therefore likely to do).

Amusingly,however, the Anti-UASF would be regarded as a 51% attack, if miners engaged in at after it had been successfully activated and used. This is because it would indeed be unreasonable for Miners to expect Users to be in constant contact with each other about which tx types are-or-are-not allowed. Miners would need to justify this decision to a confused and annoyed audience, which to my knowledge they have no real way of doing2…if a tx type is allowed, it must be allowed forever.

2. Revenue Incentives

This part of the argument goes as follows: Miners have an incentive to maximize their revenues. Each transaction that is “filtered” (ie “censored”) by the Anti-UASF, represents a fee that is not paid to miners. Thus, filtration decreases revenue. And, therefore (or so it seems), revenue-maximizing miners should never filter txns.

However, we already live in a world where miners filter some txns from the chain – invalid txns and double-spends. Miners will never include these txns in blocks, no matter how high a fee the sender includes. So it is possible in principle!

After all, some UASFs might be bad – ie they might allow transactions that somehow harm the health of the chain. Perhaps these txns are too cumbersome to validate, or perhaps they encourage behaviors that are unwanted by the economic majority.

There is a second way in which filtration (“censorship”) might actually be revenue-maximizing for miners. Imagine for a moment that a [nonwitness] blocksize increase is what is best for the bitcoin price – it will cause miner-revenues to increase. And further imagine that the most effective way for miners to get this increase is with a hardfork that has broad consensus. And finally assume that, the most effective way to achieve such a consensus is to hold SegWit hostage, to use it as a bargaining chip to induce a key group of intransigents to join your coalition. If all of these things are true, then the Anti-UASF actually would be the revenue-maximizing behavior. In other words, the “PoW/revenue incentives” would indeed be keeping miners honest…miners would “honestly” be blocking SegWit. Blocking SegWit would cause the Bitcoin software to improve faster.

Other Comments

Market For Lemons Problem

A serious weakness of the UASF is that it offers a service that, by definition, has never been used before. All current users have, by definition, been getting along fine without it. While we might expect the UASF-ed feature to be popular, until it is allowed on chain we will never know for sure.

This is relevant because, when pro-UASFers claim “People really want this! To go without it is a grave injustice!”, this claim will be “cheap talk”. We have no way of knowing if it is true, or if the UASFer is just trying to lobby for something that he personally likes, but is otherwise not very interesting.

Openness to Persuasion

The more notice miners can give users that they intend to use Anti-UASF, the more effective the Anti-UASF is. Correspondingly, the best way for Upgraders to salvage the UASF, would be to plug their ears, and ignore all communications from Miners. But, unfortunately, this is nearly impossible, as Upgraders need to have their ears open in order to hear about the UASF in the first place – Upgraders are, in general, likely to be some of the most connected, most aware participants in the entire space, to their detriment.

Prey Oddity

Rick Falkvinge would like to undo SegWit, even after it has been activated, if there’s no hard fork to 2MB. As I have explained, that is very difficult to achieve post-activation. Although, as I pointed out in a footnote, SegWit is an exceptional case.

I bring it up again, because I have some advice for both sides.

If you want to make the SegWit soft fork as game-theoretically-secure as possible, my advice would be: stop talking about SegWit. Don’t mention it, don’t acknowledge anything strange about the way it was activated. Just refer to SegWit transactions as “Bitcoin txns”, or “0.15.0 transactions”. And you should act confused when people bring SegWit up. Your goal is to frame censorship as an unjustified attack, of which SegWit-censorship is just some arbitrary subset that no one understands or could understand. The story, according to you, is that miners went crazy and started censoring transactions at random.

If you want to yank SegWit, you get the opposite advice: keep talking about SegWit. Point out how it was activated in a strange way. Your goal is that everyone who knows about Bitcoin also knows about SegWit, and the SegWit conflict, and the terms and conditions of the NYA. The story, according to you, is that it was always the deal that SegWit and 2x were an atomic package, and that everyone knew about the deal and everyone [implicitly] agreed to it. As I insinuated above, your task is much, much harder – plenty of people will be able to say that they disliked 2x more than they liked SegWit, but now that they have SegWit they don’t see why they should give it up. SegWit has some game-theoretic weakness like the different Bech32 address format, and not having a GUI for a while. These make it stand out as weird. It is probably too late for your side, but if the experiment is run I will be observing the results very carefully.

Implications

-

The main implication is clear: miners control all soft forks, whether “user activated” or not. The battle fought over SegWit will, if acrimonious conditions persist, have to be re-fought for Schnorr signatures and Simplicity and everything else to come.

-

A second clear implication: if Upgraders have “economic majority”, but lack “51% hashrate”, then what they actually want is a hard fork, not a soft one. The pro-Upgrade users want to force a split, and force the creation of a new network.

Interestingly, Upgraders would probably want to keep the exact same proof-of-work algorithm as before. As with variation 2 [above], this is strategically valuable because it minimizes collateral damage. In other words, Upgraders are only punishing Miners for rejecting SegWit, and not for any other arbitrary reason [and least of all because Upgraders expect Miners to hand over control of the system, carte blanche, to whoever complains the loudest, which would be an unreasonable expectation]. In this case, the “HF UASF” is very similar to the UASF as it was originally intended.

-

Third, I do not believe that this news is as bad as it may seem. It is true that Miners may not always have the network’s best interests at heart (they may have altcoin investments, or be under duress). If so, it is better to learn this fact sooner rather than later. It leads to a discussion of the PoW change…a malice-reactive “UAHF”. An Anti-UASF helps the users build support for the PoW change, because the PoW change cannot proceed while there remains any ambiguity about its purpose.

-

Fourth, the UASF is itself a threat. The idea of using social media campaigns to alter the Bitcoin protocol, is basically my worst nightmare. To me, a UASF hat does not seem, in earnest, that different from a Trump Hat or a Clinton bumper sticker. The implication is that Bitcoin is governed by social pressure. We cannot allow that to happen – social pressure is exactly what science and progress have rebelled against for centuries. Social pressure, rule of the “experts” (ie “authorities”), is the path to stagnation, collectivism, and misery.

Conclusion

UASF actually unsafe, could result in a loss of funds. Ironically, it is less safe than the MAHF I described in my previous post.

Footnotes

-

Bram Cohen proposed a PoW change which he claims is a soft fork. However, he admits that making sure that the fork remains soft into the future “…is an interesting problem which I’m not sure how to do off the top of my head”. Moreover, his solution requires at least one or two months to take effect, since the original difficulty cannot fall by more than a factor of four. I actually don’t think his proposal will work, because if there is a dispute over which chain is “longer”, un-upgraded nodes will ↩

-

Of course, there is one clear exception to this paragraph: the SegWit2x New York Agreement. Since “SegWit” and “2x” are supposedly conditional on each other, miners could plausible call off both of them at the same time. Miners would want to do this without surprising anyone or “crossing the line” of what is considered acceptable withdrawal-from-NYA behavior. Certainly Variation 1 (above) would be out of the question in this case. ↩