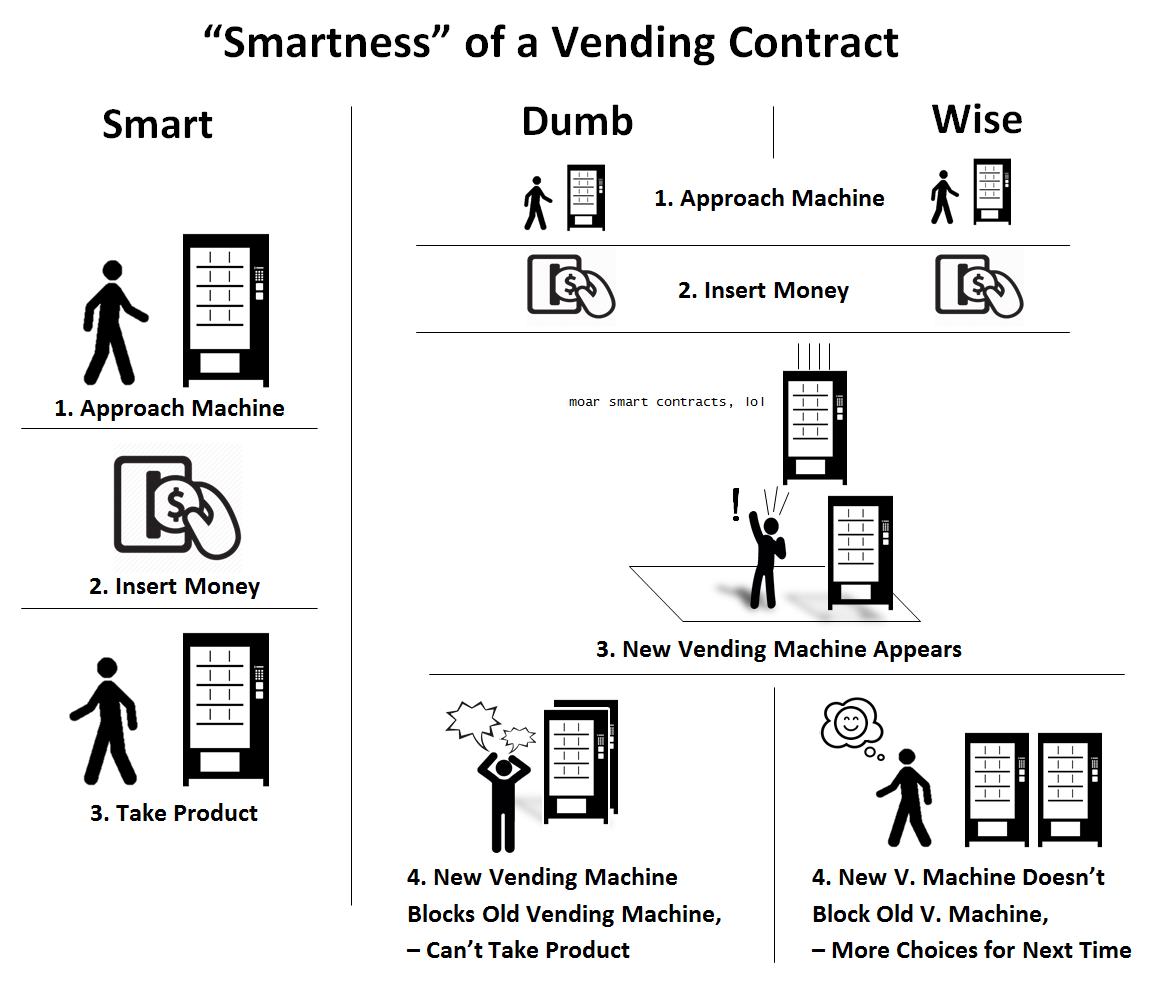

Wise Contracts are “smart” and “cooperative”. Without cooperation, smart contracts can become dumb.

This is mostly a blog-post-format reboot of the first three videos in this sequence.

Smart Contracts

A smart contract is a contract which enforces itself.

“Smart contracts” is a phrase which is often difficult to define.

Let me help: a “smart contract” is a contract which enforces itself! Nick Szabo gave the example of a vending machine. You insert the money, and the machine lets you take back either [1] your money, or [2] some merchandise.

Cryptography: Very Very Smart

Szabo’s vending machine is not quite as “smart” as it could be –according to our “self-executing” definition– because someone can steal the items (by smashing the glass or tipping the machine over), or disable the machine (by unplugging it). Ultimately, there’s “dumbness” to the contract, because it (the machine) doesn’t completely execute itself. The machine relies on the building for power, on courts/police for protection, and on other individuals to maintain it, stock it, and collect money from it, and so forth.

In contrast, cryptography allows one to construct rules which are literally unbreakable.

It is really quite extraordinary: one human “making” something that no human can “unmake”.

"The contract's legal, binding and completely unbreakable–even for YOU."

-Ursula, to King Trident

( The Little Mermaid, 1989 )

Originally, crypto could only protect files (by putting them in metaphorical safes or envelopes). But it later progressed to digital identities, and ultimately, payments (ie Bitcoin). Since Bitcoin is peer-to-peer, it is itself a smart contract, in the sense that, if you turn it on, no one else can turn it off. A single peer can regenerate (or even maintain) the entire network.

As a result, the post-Bitcoin era is one where Szabo’s vending machine can be much more powerful. The physical “machine” is unbreakable –the glass cannot even be scratched, if all the world’s armies were to turn and fire at once–, the machine cannot be cheated or deprogrammed, it will always operate with perfect reliability all the time, and it cannot be unplugged (because the customers power it, by pressing the buttons).

Above: the ‘cryptex’ from the Da Vinci Code movie.

Examples of Cryptographic Smart Contracts

These include:

- Atomic Swaps (ie, exchanging X coins on Chain 1 for Y coins on Chain 2, upon the release of hidding information R).

- Escrow and/or Conditional Bet (pay X to Y if trigger Q is activated, else pay Z to Y).

- Pay to reveal data

- Renting hard drive space

Value of Smart Contracts

Smart contracts have a number of advantages. The first is that they are written in computer code, which makes them 100% unambiguous. No ‘interpretation’ is required; no subjectivity. Legal and Economic theory are clear: enforcement ambiguity = bad for commerce.

A second huge advantage is that smart contracts are entirely self-contained. All of the ‘evidence’ of fulfillment is cryptographic. There is absolutely no need for a ‘fact-finder’ such as mediator, judge, or jury. Courts are very slow and deliberate (for good reason), but smart contracts can be resolved at the speed of the CPU – thousands per second. And as the tech improves, smart contracts get even faster.

Of course, there is a trade-off: being software code, smart contracts are very hard to write, and their influence is limited to cyberspace.

But in general this is fantastic – an unambiguous contract, where you can get the ruling you deserve, inside of a single minute, at zero marginal cost.

The traditional contracting system is, of course, quite expensive. A paper contract requires courts, to interpret contracts and resolve disputes. These courts, in turn, require baliffs and policemen, if their orders are to be enforced anywhere. This public-service monopoly-on-violence implies membership fees of some kind (ie, taxes), collective-action (ie, “government”), and preference-aggregation (ie, democracy, monarchy, etc). In any society of reasonable size, this in turn implies representation, specialization, legislature, politicians, and all the rest. At larger scales, significant corruption is inevitable. If any of the violence-monopolies disagree with each other, there will be wars!

That’s a lot of overhead! And SC-users must still pay their ‘real’ taxes, of course. Just as they must tolerate ‘real’ wars (and just as they make use of paper contracts themselves). Nonetheless, you see the appeal of moving in the digital direction.

Wise Contracts

Wise contracts are both “smart” and “cooperative”. This is necessary because one smart contract can “dumb” another one down.

Wise Contracts are two things. Firstly, they are “smart”; they execute themselves.

Secondly, they are also cooperative, they don’t attack each other.

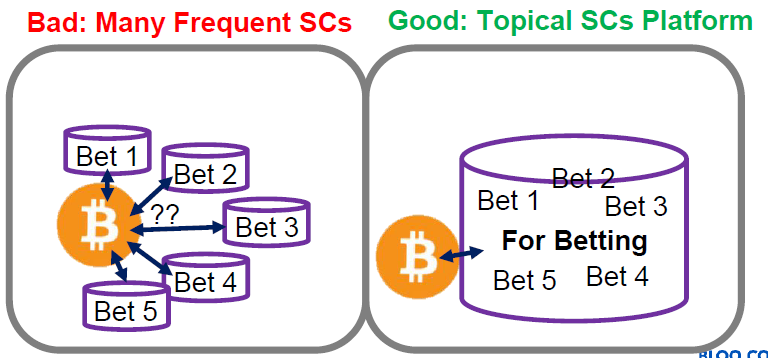

Cooperation is important because, smart contracts can attack each other, thereby ‘dumbing’ each other down and preventing themselves from executing at all (let alone automatically). Often, these harmful, non-cooperative interactions are profitable for attackers.

Two examples I gave last summer were:

- A simple, profitable contract, which steals Oracle data, destroying the Oracle in the process.

- A complex, profitable contract, which ‘steals’ Bitcoin, disrupting the Bitcoin cryptosystem in the process.

These examples might be hard to understand. Instead, an analogy might be helpful: imagine a corporation, where anyone can work. The CEO can’t fire anyone, no matter how unproductive, or outright disruptive they are.

For example,

- One employee does nothing but slack off all day…at the end of the day he copies the work of the most productive employee in the building. As a result, the other employees can’t get credit for their hard work, and they all slack off more and more. Total productivity grinds to a halt, in a USSR-style free-rider dystopia.

- One employee starts his own competing company, within this company and using company resources. He can thus undercut the existing company (which quickly goes bankrupt).

Biologically, it is comparable to an organism which does not have an immune system. Since it is “permission-less”, it “allows” qualities to emerge which contradict the qualities of the underlying organism. This (infection, cancer) results in the death of the organism (and everything in it).

The result of this, is that the addition of some contracts can subtract the effects of others. As if King Trident could invalidate Ursala’s contract, just by writing one of his own. Or as if a brand new vending machine could somehow cause an older vending machine to no longer work.

Since the entire point of a contract, is that the signers expect it to be enforced, this “dumbness” phenomenon ruins the who ‘smart contracts’ idea.

We need a way to prevent smart contracts from “dumbing” each other down.

Enforcing Cooperation

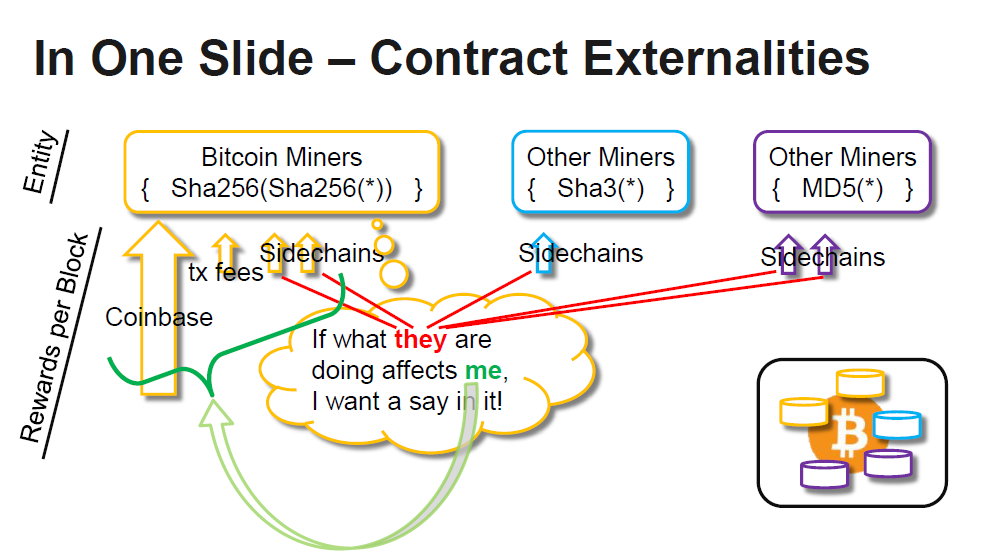

Sidechains provide most of the solution, as sidechains are firewalled from each other. Sidechains filter out messages that don’t belong to their chain, while sharing the same value-token and economic network. In this way, we can add or subtract chains as we like, allowing new messages (ie, new ‘smart contracts’).

But the technical firewall does not necessarily prohibit harmful interactions among chains, at the “macro-chain” level.

To upgrade our firewall, we rely on a simple capitalist principle: uniting ‘ownership’ and ‘control’. Bitcoin-miners ‘control’ which sidechains are added (and can remove them), and these same agents ‘own’ the chains and enjoy the benefits (or costs) of maintaining them.

This is accomplished, in Drivechain, by requiring withdrawal-proofs to use the ‘parent’ mainchain’s PoW, instead of the sidechain’s PoW. In this way, mainchain miners always get the last word – on everything that affects their token (even if the sidechain uses a different PoW algorithm, or PoS, etc).

Above: a slide from my presentation series.

Motivation and Equilibrium

We can safely assume that miners will try to maximize the purchasing power of their total block reward across all chains. Most obviously, miners would do this to earn more money. In addition, as time passes, miners who do not engage in this maximization strategy will tend to go out of business. Eventually, the miner’s “maximum” revenue will be also be “exactly as much money as we need, in order to stay in business”. At which point miners will have no choice but to consistently maximize from this point out.

In addition, it is probable that miners will be able to maximize in this way, for free (ie, without actually doing anything). An implicit threat of miner-action is sufficient. This is because smart contracts are difficult to create – the developer must move first, investing tremendous time and effort in writing the software code. The miners can move later, at minimal effort, to block the contract if it misbehaves.

If we use a tripartite analogy (where miners are police, developers are legislators, and nodes are the judiciary), then the “sidechains” concept would be comparable to a world where citizens are free to opt-in to a new set of laws. The concept of merged-mining (ie, placing the same miners in charge of enforcing both sets of protocol rules), is akin to placing the same police officers in charge of enforcing all of these laws. It is difficult for me to believe how it could be any other way – if the laws were enforced by a different ‘competing’ group of police offers, how would we resolve any disputes between the two groups? This seems, to me, to be reintroducing the very “wars” and other ‘expensive competition’ that we originally wanted to replace!

Finally, this idea here, of ‘wise’ contracts, is akin to allowing the police to refuse to enforce some “new laws” if these contradict “old laws”. Again, it is hard for me to see how anything else could be practical. Our miner police-force already charges us fees-for-service, and we don’t expect miners to process transactions which neglect to pay a sufficient fee. So, why would we expect miners to enforce laws which have a net negative fee (ie that, by collecting some positive fee-amount, their total fee-revenues nonetheless decrease)?

What this ‘wise’ idea seeks to do, is simply ‘lighten the load’ on miners, as I explain three paragraphs ago. Instead of needing to monitor each message, (which is an inordinate amount of work, given that the messages can be densely obfuscated and be subjected to endless variation), miners can simply monitor sets of messages by category.

Conclusion

To be effective, smart contracts need to work together. Or, at least, they need the freedom to work in peace, without being harassed by other workers. They need to be not only smart, but wise!

comments powered by Disqus